The Netherlands: home to wind mills, tulips… and one of the world’s ten largest fields of natural gas. But what was once seen as a blessing is increasingly viewed as a thing of the past. Craig Morris asks: is it time to break with the Dutch tradition of “pretty continuation”?

Station Wildervank of the Groningen natural gas field (Public Domain)

Your first Dutch phrase of the day: smakelijk eten (bon appetit.) Some 98 percent of households cook and heat with natural gas. This reliance is not hard to explain: in 1959, the Dutch discovered the largest gas field in Europe and the tenth largest in the world right under their feet in Groningen. The Netherlands raced to use up this resource as quickly as possible because experts mistakenly thought nuclear power would soon make gas unmarketable (an excellent example of the nuclear hype around 1959 – also see this from another Dutch firm).

Except from a speech given by the Senior Vice President of Exxon in 2013.

Fast forward nearly sixty years, and a lot of gas infrastructure is in place because nuclear failed to deliver. This reliance on natural gas has not come without criticism, however; in 1977, British weekly The Economist coined the term Dutch disease for the perceived inability of the Netherlands to innovate itself out of economic downturns (not to be confused with the recent Dutch Coal Mistake: building numerous coal plants that were immediately unprofitable). Plentiful gas, it was felt, had made the Dutch lazy. Royal Dutch Shell, the oil & gas giant, is also too big for such a small country; revenues at Shell are nearly as great as the entire Dutch economy.

But recent events have brought about fundamental change. Earthquakes began damaging homes around the Groningen field (as gas is extracted, the ground subsides). Production has therefore been cut to nearly half of the level in 2013. This year, a court upheld that production level contingent upon annual reviews against calls for a stricter reduction or complete halt. But gas is on its way out: last year, the Dutch banned gas heaters in new homes. Amsterdam now has a plan to get all homes off natural gas by 2050. The country has a 100% renewables target for 2050.

“The mind is a funny thing”

“We had to convince ourselves in our company that a future without gas is possible,” says Elbert Huijzer of Dutch energy network company Alliander. To better engage in the debate about a possible gas-free Netherlands, Huijzer had his colleagues try to develop a scenario without gas for the country. Given the dominance of gas, he and his colleagues felt that their jobs were secure. “We simply weren’t taking the threat seriously.” So he had them sit down over four days late in 2015 and draw up scenarios for a gas-free Netherlands.

“My goal was to prove the idea of a gas-free Netherlands wrong. But the effect was the other way around,” he says. To their own surprise, his colleagues found that a Dutch future without natural gas was possible. “Once we had designed such a supply ourselves, we understood the reality of the risk,” he says, “but it took a lot of time and arguing. The mind is a funny thing,” he sums up the experience.

The insight comes just in time. The head of NAM, the firm that operates the Groningen gas field, has now called for gas revenues to be put into a fund for renewables: “At the moment, the profits from gas still run into the billions, and we can invest in generating the energy of the future.”

Shell has also done an about-face. Until recently, the oil & gas giant covertly undermined the push for EU renewable energy targets behind the scenes. The antidemocratic role Shell has historically played in the Netherlands is well described in a Dutch book whose title needs no explanation or translation: Gaskolonie.

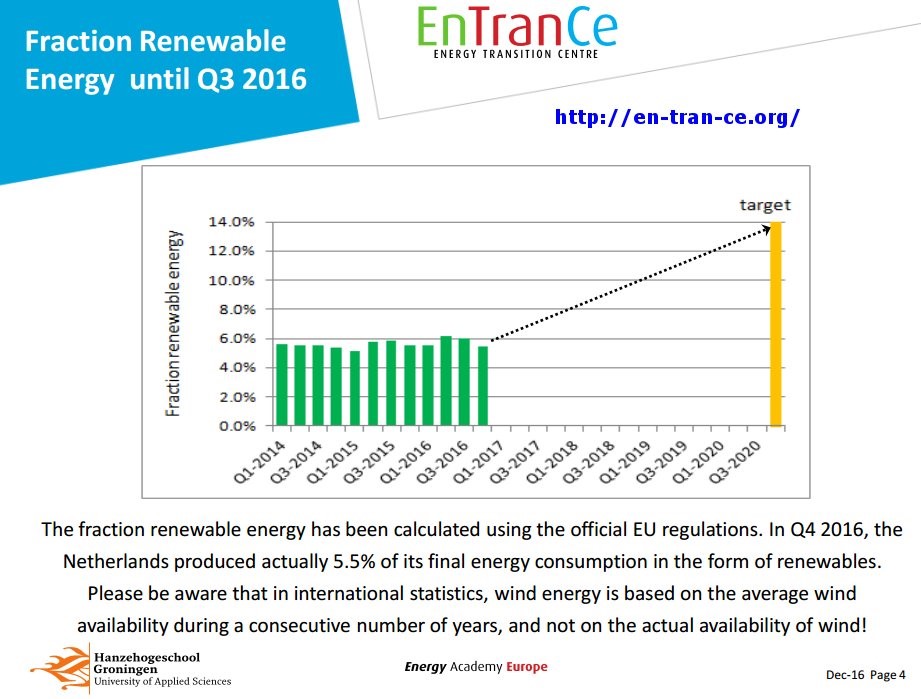

The Dutch are nowhere close to their 2020 target of 14 percent renewables as a share of final energy. Indeed, little progress is being made. Source: EnTranCe.

Recently, Shell placed a winning bid as part of a consortium for an offshore wind farm that posted a record-low price of 5.45 ct/kWh. Still, criticism remains; one energy sector expert speaking to me on terms of anonymity argues that Shell merely wants to corner the wind market for itself: “They are lobbying for one big tender of 10-15 GW. If they win it, they will dominate the wind market just like they do along with NAM and Exxon for gas.”

Clearly, it makes a difference politically who drives the transition: a small group large corporations or a broader range of smaller firms and cooperatives. Though this aspect is often overlooked, the global energy transition is a one-time opportunity to democratize the energy sector. In the Netherlands, the transition is a one-time opportunity to weaken domination by a very small, but powerful gas oligarchy.

Whatever way the Dutch go, the public first has to get its head around a gas-free future. To this end, Dutch utility Nuon (a subsidiary of Vattenfall) is sending a Cook Truck (report in Dutch) around to public spaces to sell the idea of cooking with electricity to the Dutch. Your second Dutch phrase of the day: prettige voortzetting – if you leave the table when people are still eating, you wish them a “pretty continuation.” Maybe prettige transitie would be better?

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

OT

Building of first cruise ship running on LNG started today:

https://worldmaritimenews.com/archives/213327/first-steel-cut-for-aidas-lng-cruise-ship/

Bookings are taken already(in German):

http://www.presseportal.de/pm/55827/3566582

——————–

The Dutch home owner association has a lot of questions, like if it is wise to replace an old gas boiler with a modern one or better wait for district heating to come or if it would be better getting a heat pump ….:

(in Dutch)

https://www.eigenhuis.nl/actueel/pers/2017/02/07/15/00/veh-consument-wil-snel-duidelijkheid-over-praktijk-gasloze-toekomst

“British weekly The Economist coined the term Dutch disease for the perceived inability of the Netherlands to innovate itself out of economic downturns..” I question this moralistic reading. IIRC the “Dutch disease” is a simple economic consequence in any country with a floating exchange rate of any natural resource windfall. Exports rise, imports drop, and the currency (pre-euro) rises. The manufacturing sector, where innovation is concentrated, is choked off. The discovery of oil and gas in the British sector of the North Sea had the same effect. It’s not that people stop wanting to work, it’s that it makes no difference if they do.

[…] artikel is eerder verschenen op Energy Transition en met toestemming van de auteur vertaald door Krispijn […]

[…] recently discussed, the Dutch are running out of gas. Their natural gas was of low calorific content, so more of it […]

[…] Dutch are running out of gas. But instead of trying to use the existing gas lines to switch to renewable gas, the Netherlands is […]