Despite its beautiful windmills, the Netherlands doesn’t rank that high for renewable energy production, and might miss its 2020 target. The good news is that it has launched an ambitious campaign for zero-emission public transport by 2025. Henning Twickler and Kathrin Glastra explain how the Netherlands could help pave the way for a transportation transition.

The Netherlands might be known for its windmills, but big changes are coming from the transportation sector (Photo by Uberprutser, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What is your first association when you think of the Netherlands? Among other things, windmills against a picturesque countryside score high. This is not the case when talking about renewable energy sources (RES), which have been a “non-issue” in the Dutch public debate for a long time. This comes as a surprise, given the country’s long tradition to use wind power as well as abundant water resources for manufacturing.

Even though natural conditions for renewable energy sources are optimal, the Netherlands is behind most EU countries regarding energy production from renewable energies. Only Malta and Luxembourg had lower proportions. In 2014, renewable energies accounted for 5,0% of the Netherlands’ final energy consumption. The use of RES is somewhat higher, thanks to energy imports. In 2016, the Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek reported that the RES share in gross energy consumption is expected to be around 11.1 %, with the long-term expectation of 11.9 % by 2020 – missing its intended target of 14% RES by 2020 under the European objectives for 2020.

The Netherlands is home to the largest natural gas field in Europe and is the second European exporter (after Norway). But the natural source comes at a price: since 1986, around 1000 induced earthquakes have been registered in the area of Groningen. Slowly but surely, the Dutch are realizing the devastating consequences of gas extraction in the densely populated areas, leading to what is referred to as a “gas-hangover”.

Despite the lacking momentum as far as a transition of the energy system is concerned, a silver lining can be seen: In April 2016, an administrative agreement was signed to achieve zero-emission public transport in the Netherlands by 2025, sending a clear signal to local authorities, vehicle producers and public transport providers. This agreement is also the outcome of the work done by the ‘Zero Emission Bus Transport Foundation’ (SZEB) which advocated for emission-free public transportation in the Netherlands since 2011. With the new agreement and a substantial number of electric buses already operating on Dutch streets by early 2017, the foundation now finished its activities.

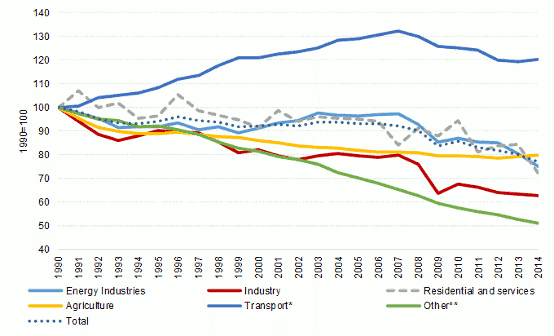

The decision of the Netherlands to phase out petrol powered public transport is in line with the EU’s climate and energy framework that wants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% in 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Investments in the electricity sector alone will not be sufficient to bring emissions down to the required level. Transportation is an especially major polluter, causing almost a quarter of Europe’s greenhouse gas emissions. While other sectors have seen a gradual decline in emissions since the 1990s, those from transport have only started to decline in 2007 and are still well above 1990 levels (Figure 1).

Within this sector, road transport accounts for 70% of emissions. The biggest advantage of emission-free public transport is clear. It addresses the problem of greenhouse gases in a twofold way: 1) by not relying on fossil fuels; and 2) by collectivising transport – which would not be the case if only electric cars were promoted.

Changes in emission levels over the years. (Source: EU commission on climate action)

The SZEB ran a pilot project with one electric bus in Maastricht since March 2015. Currently, there are 4 electric buses in the city and even more are operating in Venlo. The expansion of operations is happening fast because of new public transport concessions which started in December 2016 in the southern provinces of North Brabant and Limburg. In Eindhoven, there are 43 electric buses operating since December. As of January, there are 14 buses on the Dutch islands of Vlieland, Ameland and Schiermonnikoog and 18 more to come in Haarlem. The Netherlands consequently serves as a testing ground for a potential use of zero-emission transport in bigger EU countries such as France and Germany.

The Dutch experience produced a number of insights. Firstly, both private and public parties acknowledge the great potential of zero-emission public transport. Nevertheless, some concerns remain. Several transport companies have expressed the need for longer concession periods in order to make investments in emission-free vehicles financially more attractive. Electric buses, for example, become more profitable when used over a longer period of time because of a lower total cost of ownership (TOC).

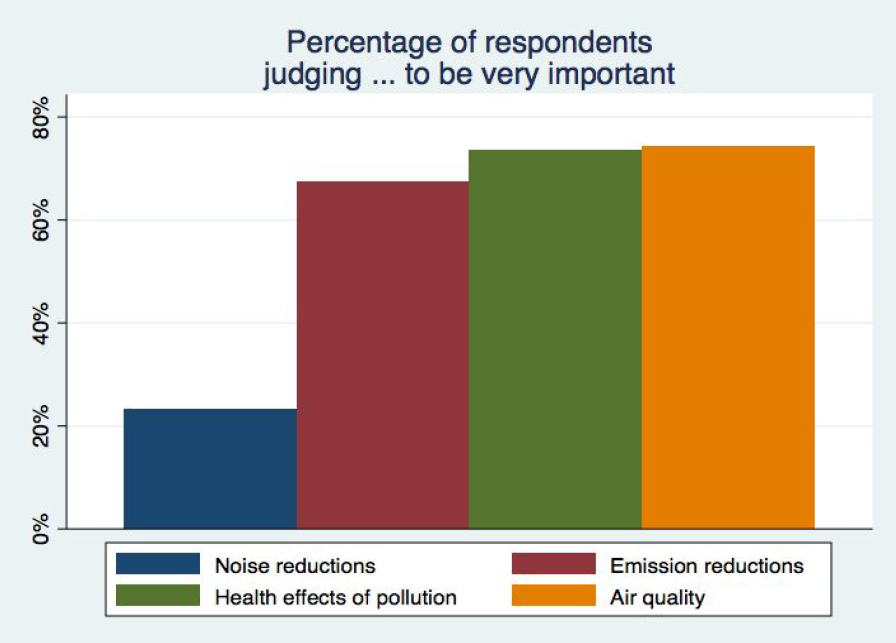

Secondly, survey research by Maastricht University students showed that citizens as well as tourists greatly value zero-emission vehicles. 62% of survey participants were convinced that zero-emission bus transport was very valuable for the city of Maastricht while 28% thought it was at least somewhat valuable. Furthermore, it became clear that air quality, health effects of pollution and emission reductions are primary concerns of citizens. More specifically, 74% judged air quality to be important while 73% were much concerned with the health effects of pollution. The reduction of traffic noise was judged to be less important (Figure 2). One can well imagine that similar views exist in other European cities.

Concerns related to Diesel buses

Therefore, zero-emission mobility is a way to respond to citizens’ concerns. Despite the deficiencies in the Dutch energy transition, a silver lining can be seen in the field of public transport. The country has some way to go but introducing zero-emission buses is a step into the right direction.

About the authors:

Henning Twickler was an intern in the Climate and Energy Programme of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union. He worked on a research project for the Zero Emission Bus Transport Foundation in Maastricht while completing his master’s degree in Public Policy and Human Development.

Kathrin Glastra is Director of the European Energy Transition Programme of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.

No evidence is cited for the proposition that electrification of buses will shift demand their way and “collectivise transport”. This is possible – the ride is better and quieter – but the effect is not likely to be large, unless the policy is coupled with bans on ICE private cars in city centres. The dubious claim is not necessary to make the case for the excellent new policy, which is fully justified on the sure-fire grounds of climate change and urban air pollution. Cutting pollution may also encourage more cycling and walking, but I’m not making great claims for the possibility.

I have been following off-shore wind developments in NL. The recent auctions have delivered prices close to if not less than wholesale elec prices & there is a significant appetite for off-shore wind with a pipeline of perhaps 8GW. So in that sense, I’d suggest that the Dutch are now starting to press the loud pedal on RES. In the case of transport – I can see widespred EVs – buses? maybe – perhaps also fuelcell or SNG. The latter could be produced using increasingly low-cost elec from off-shore wind

The energy politics of the Netherlands are of a colonial style, the transport of the merchants isn’t tackled at all. Neither the growing number of (mega-) trucks or ships or aeroplanes, for example is the expansion of the airport Schiphol still going ahead.

Austria has banned the expansion of Vienna airport Schwechat yesterday, the emissions causing climate change being the major reason:

http://diepresse.com/home/wirtschaft/recht/5167515/Keine-dritte-Piste-fuer-den-Flughafen-Wien-Schwechat

The Dutch merchants blow the CO2 into the air whenever and wherever they please to do so, RE’s imported are quoted as greening the national balance sheet. For example are the Netherlands the main buyer for German electricity:

https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/de/documents/publications/studies/Stromerzeugung_2016.pdf

but the emissions stay in Germany’s balance sheets. And not in the atmosphere ….

The Dutch crown and state is still holding their protective hands over Royal Dutch Shell (gas field Groningen!) and over the atom Mafia as well.

The Dutch public holds shares in their very undertakers.