What would Brexit mean for the proposed nuclear reactor at Hinkley and England? No one really knew—until the new government in Downing Street announced the refurbishment of its nuclear submarines. Shortly thereafter, London confirmed that it remains committed to Hinkley—before postponing a final decision once again. Craig Morris explains.

Hinkley power station in the distance ; the proposed reactor is running into problems from all sides (Photo by Nilfanion, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Two years ago, a retired British MP gave me a tip under the condition of anonymity: “look for connections between Hinkley and British nuclear weapons.” The British are planning to construct a new European Pressurized Reactor (EPR), and the project has come under scrutiny for numerous reasons:

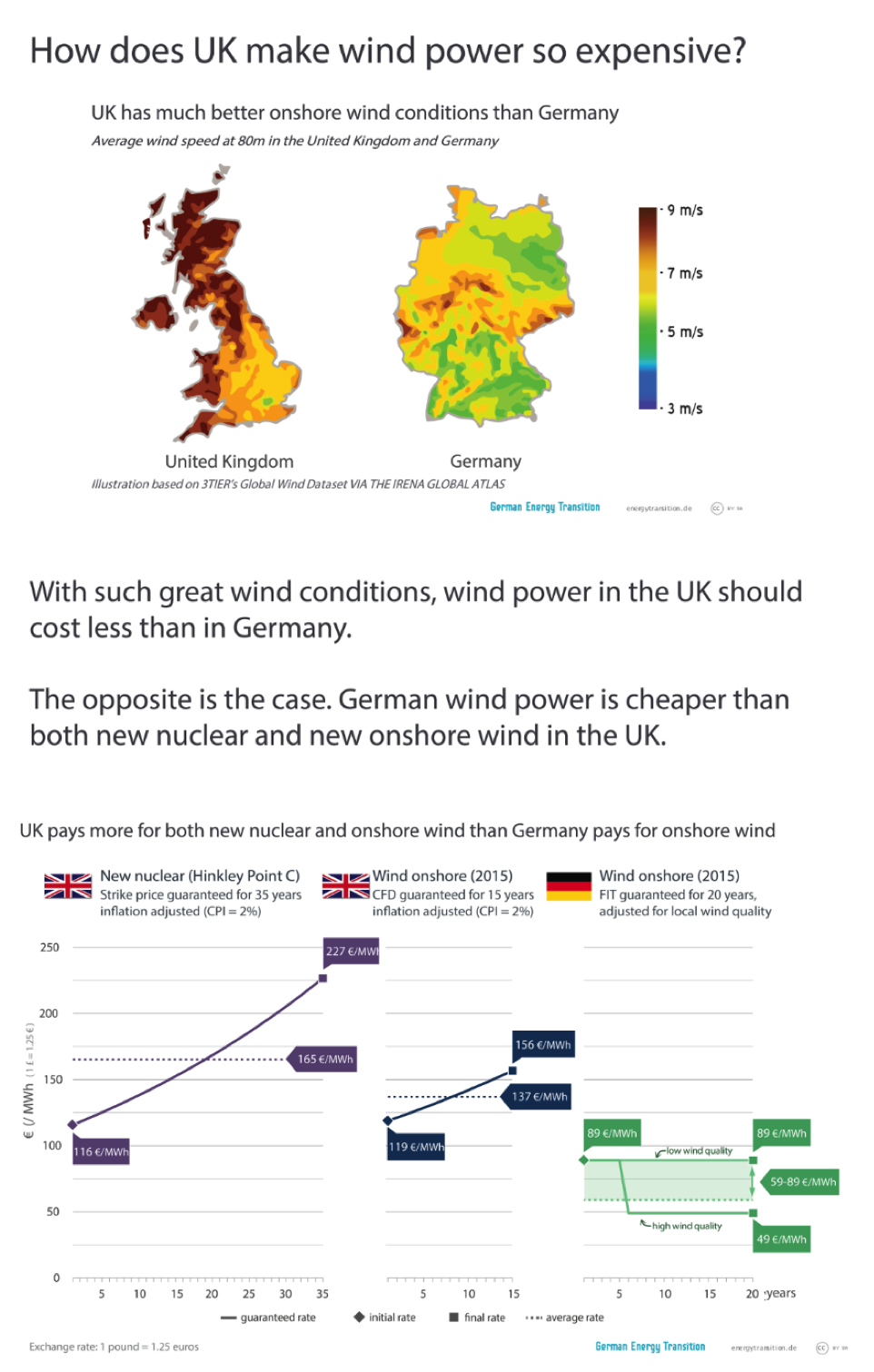

- the price tag (the electricity will cost more than new renewables);

- the builders (France is behind the technology, but China will be providing much of the funding); and

- the specific reactor design (no EPR has ever been completed anywhere, and the two under construction are over budget, behind schedule, and may potentially be abandoned instead of completed).

The project is a boondoggle, as Jeremy Leggett recently explained. Just days after news that the county’s nuclear submarine fleet (Trident) will also be renewed, we heard that Hinkley will go ahead. But on Thursday, the final decision was postponed until the fall.

Of course, a new government could simply wish to clear out the backlog upon entering office. Both Trident and Hinkley have been in the lurch for years. And a connection is not easy to document; I have been looking for the connections the British MP hinted at, but they are hard to come by.

But not impossible. Two British researchers, Andy Stirling and Phil Johnstone, have documented the connections quite well. They write that maintaining a small fleet of nuclear submarines also means maintaining:

“a significant domestic role in dedicated supply chains and industrial infrastructures around civil nuclear power. Viewed this way, the UK needs to maintain within its own borders, the requisite specialist production facilities, supply capacities, design capabilities, training infrastructure, and regulatory and consulting organisations and expertise… It is not necessary… that the UK lead on supplying entire civilian power stations. All that is needed, is simply that sufficient spill-over and trickle-down be redirectable to sustaining the basis for the producing nuclear submarines.”

The connection seems simple enough. Yet Stirling and Johnstone have not had an easy time getting the word out; apparently, journalists tell them the issue is “hard to understand.” Wherever the public chooses not to investigate the civilian or military nuclear sector because it is too complicated, the sector progresses more easily. Transparency kills nuclear. As pointed out in a comparison of the history of nuclear power in France and Germany, the Germans used courts to hold the sector accountable, whereas French judges refused to hear the cases because they said they simply couldn’t understand the subject matter.

Does this mean the reactor will be built?

Just because Downing Street remains committed to Hinkley does not mean the project will be completed, however. EDF, the French investor alongside the Chinese, has enough problems at home. Owned largely (85 percent) by the French state, the utility was raided last week by French investigators under suspicion of a lack of transparency concerning both Hinkley and maintenance costs for the French nuclear fleet, which EDF operates. A few days earlier, the operating permit had been suspended for one of the Fessenheim reactors—the country’s oldest.

The problem is a high carbon content in the steel used for the containment vessel—an issue that seems to be plaguing the shells provided by Areva’s forge. The Flamanville EPR reactor also revealed similar flaws that may call the entire project into question, as the reactor is the same type as the one that would be built in the UK. To make things worse, irregularities in the documentation from the forge were recently discovered going all the way back to the mid-1960s.

The big question is therefore whether the UK will go ahead with a conventional new reactor if the EPR does not materialize—maybe using a design from Russia? If the country cannot do without nuclear power to maintain the supply chain needed for its nuclear submarines, some new build will eventually be necessary because the country faces an unannounced nuclear phaseout in the first half of the 2030s as its fleet of nuclear reactors ages.

The existing reactors could simply be used for more than 40 years if the idea can be sold to the British public (to the extent the government even considers public approval necessary). Service life extensions might raise concern about safety, as could the option of a conventional reactor from, say, Asia; the EPR’s selling point is its alleged greater inherent safety.

Of course, renewables are another option; the UK is the Saudi Arabia of wind in Europe. But wind turbines aren’t useful for the nuclear supply chain, so the British would need to hone their diplomatic skills in soft power if they went renewable. Stick with nuclear, and Boris-style diplomacy will do.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. He is a co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende.