The Energiewende is a federal energy policy that started off as a grassroots movement. Just a few years ago, investments in the sector clearly revealed those origins. But amendments implemented in 2014 changed the trend fundamentally. If the government does not address the issue soon, one can only include the outcome is intentional. Craig Morris takes a look.

A sustainable housing community in Freiburg, Germany. (Photo by Andrewglaser, modified, CC BY-SA 3.0)

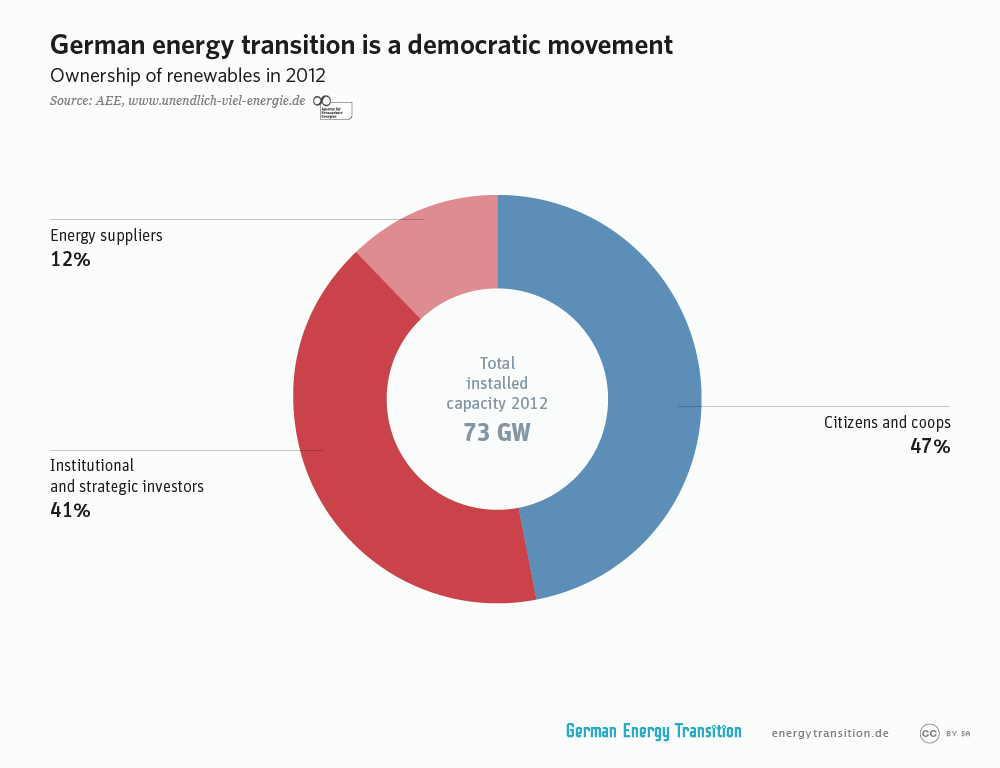

One of our most popular charts is definitely the one below showing that nearly half of the renewable power generation capacity built came from citizens.

But notice the year: 2012. What’s been going on since then?

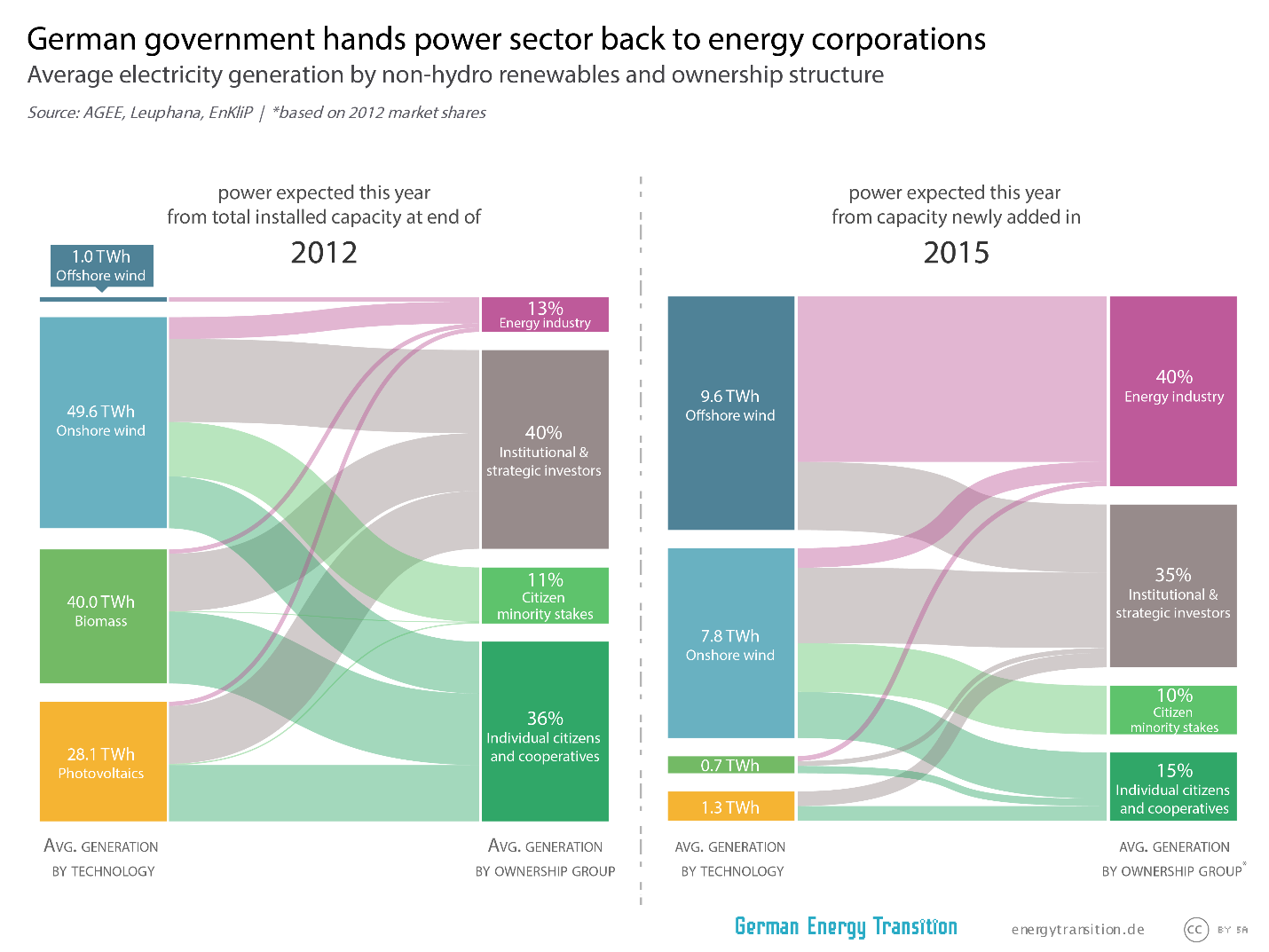

Frankly, we don’t know; this study for 2012 has not been repeated, and I know of none in the pipeline. Yet, there was a tremendous shift in 2015. To make it clear, we switched the metric from GW (gigawatts: the size of the generators) to TWh (terawatt-hours: the amount of electricity generated). This shift essentially means we are no longer focusing on who made the investments (investors pay for GW), but instead on who is making money (you get paid for TWh).

The results are clear.

On the left, we see community ownership (citizens and cooperatives including minority stakes) coming in at 47%, compared to only 25% on the right. Community energy has been cut in half. At the same time, the share of the conventional energy firms more than tripled from 13% to 40%. In terms of energy source, the shift is also clear. Germany has moved from photovoltaics and biomass (roughly half of which was community energy) to offshore wind (none of which is in Germany). The big unknown is onshore wind, which still makes up around 40% of non-hydro renewable power supply; for a lack of further information, we simply assumed the ownership structure remained exactly the same, but a shift in the ownership structure may have also taken place here as well.

Methodology

The power production figures for 2015 are projections, not the actual numbers for that year. For instance, a wind turbine that started power production in early July 2015 will only produce half of its potential that year; one that went up in late September, closer to a quarter. To account for these effects, we calculated a theoretical average year of power production based on average capacity factors for each technology that year in Germany (data source, PDF in German):

- offshore wind: 49%

- onshore wind: 25%

- photovoltaics: 11%

- biomass: 79%.

Likewise, the figures for 2012 are a generalization based on the following capacity factors by technology at the time (the increase for onshore wind since then is global and dramatic because of innovation):

- offshore wind: 49%

- onshore wind: 19%

- photovoltaics: 10%

- biomass: 80%.

Think of it this way: the left part of the chart shows how much electricity the systems installed by the end of 2012 could be expected to produce this year, whereas the right part shows how much could be expected this year from systems installed last year.

Furthermore, the left chart part above is for all years up to and including 2012, whereas the part on the right is for power from new installations in 2015 alone. While we do have a good idea of the ownership structure as of 2012, we have no idea what it was in 2015. The chart on the right for that year therefore merely applies the past ownership structure to the present.

This methodology is so sloppy, we almost didn’t produce this chart. But then we realized that truly disproving these figures would require an update of the 2012 study, which is exactly what we want: an actual examination of this issue. In all likelihood, it would find that we are off by a few percentage points, but it’s hard to say whether it would be up or down. The message would still be the same: the German government’s policies since 2014 are pushing back the community energy proponents who got the Energiewende started and handing the power sector back over to the energy companies that did not believe the Energiewende would work.

Back in 2009, Germany’s Big Four utilities made up the only one percent of investments in renewables. They were busy planning dozens of coal plants back then. Of course, German utilities switching investments from coal to renewables is good news. Governmental policy preventing the grassroots movement from remaining involved, less so. But go ahead, dear Economics Ministry, prove us wrong. The ball is in your court.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. Thomas Gerke (@Zoido4Design) created the graphic.