While the amount of electricity generated from coal has declined for two years in a row and utilisation rates of coal power plants have been going down, energy companies continue to build new coal-fired generating plants at a rapid pace. Worldwide the equivalent of 1500 coal plants is under construction or in various stages of planning, Karel Beckmann writes.

Coal power in construction either dropped or remained level, but rise in China and South Asia. (Photo by Marcel Oosterwijk, modified, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Building new coal plants is “a massive diversion of resources away from clean energy technologies that must rapidly be developed if the worst effects of climate change are to be averted”, notes the report, “Boom and Bust 2016: Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline”, published in March. Yet worldwide 338 GW of new coal capacity was in construction in January 2015 compared to 330 GW a year ealier. In addition, 1,086 GW was in various stages of planning compared to 1,083 GW the year before.

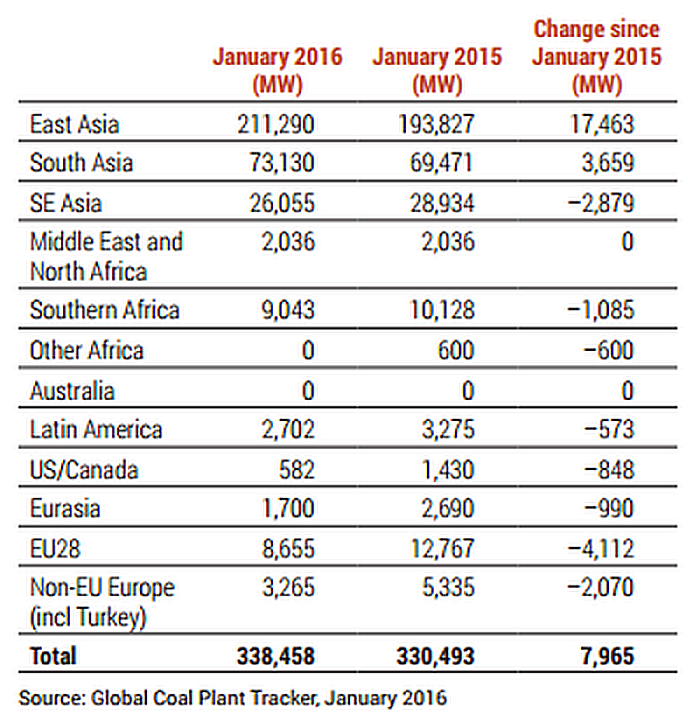

The rise in construction and pre-construction activity was solely due to China and South Asia. Outside these regions, coal power construction either dropped or remained level:

Change in Coal Power Construction Activity by Region, 2015-2016 (MW)

Problem tackled

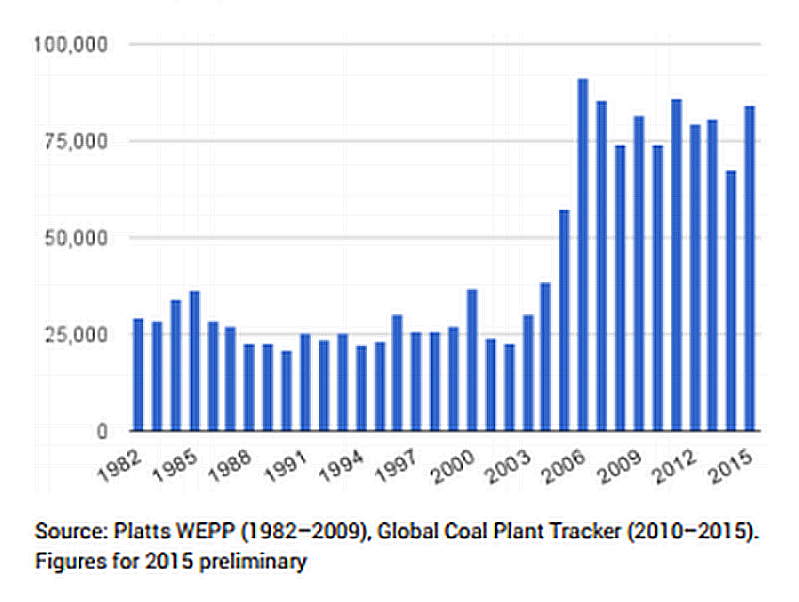

Looking at construction activity from a longer-term perspective, from 2006 on the pace of global coal plant building rose steeply, as China added huge capacities. There was a downturn in 2014, but last year saw an upswing again. However, according to the report, “with both pre-construction and construction activity shrinking in most regions, there is good reason to expect a downswing in new coal plants in future years outside China.”

Within China, “the central government has reportedly ordered provincial governments to suspend new approvals in 13 provinces and regions through 2017, and to halt initiation of new construction in 15 provinces and regions”, notes the report. “This is an important step that, according to an analysis based on the Global Coal Plant Tracker data, could see up to 183 GW of new projects suspended, and signal that the problem is being tackled. However, the large amount of capacity already under construction across the country, or under development in provinces and regions not covered by the new restrictions, means that much more stringent measures will be needed to stop the ballooning of capacity.”

New Coal Power Worldwide, 1982-2015 (MW)

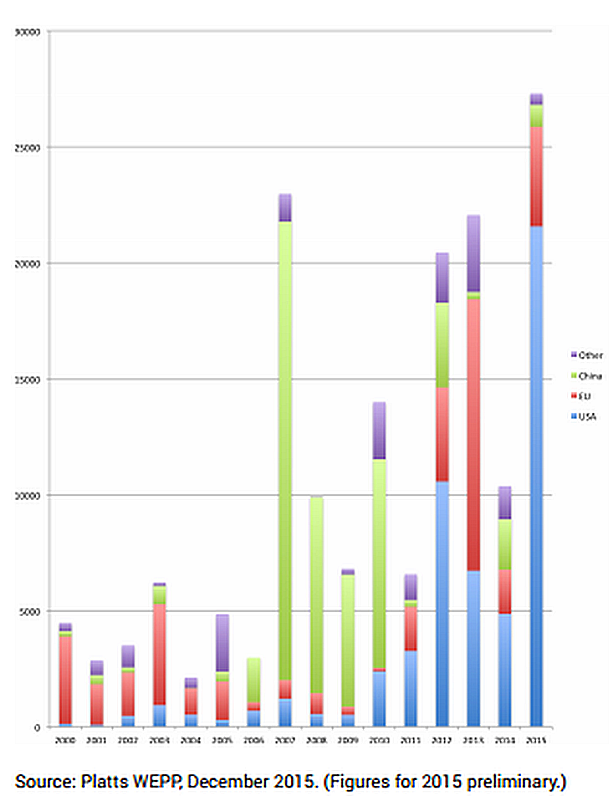

Retirements of old coal-fired power plants have also grown since 2007, although they are not large enough to compensate for the construction of new capacity:

Global Coal Power Retirements, 2000-2015 (MW

By far the most retirements occurred in the US, followed by the EU.

Although the coal-industry argues that replacing older plants with more efficient new ones results in a net gain for the climate, the authors of the report deny this: “as shown by ‘commitment accounting’ studies that estimate the lifetime emissions of energy infrastructure, larger and newer plants actually contain a greater amount of committed emissions over their lifetimes than smaller, older plants. For that reason, replacement of older, less-efficient capacity with newer, more-efficient capacity should not be seen as a climate solution. Rather, it locks in a carbon emissions trajectory that is inconsistent with the 2°C commitments made at COP21 in Paris.”

Poorest countries

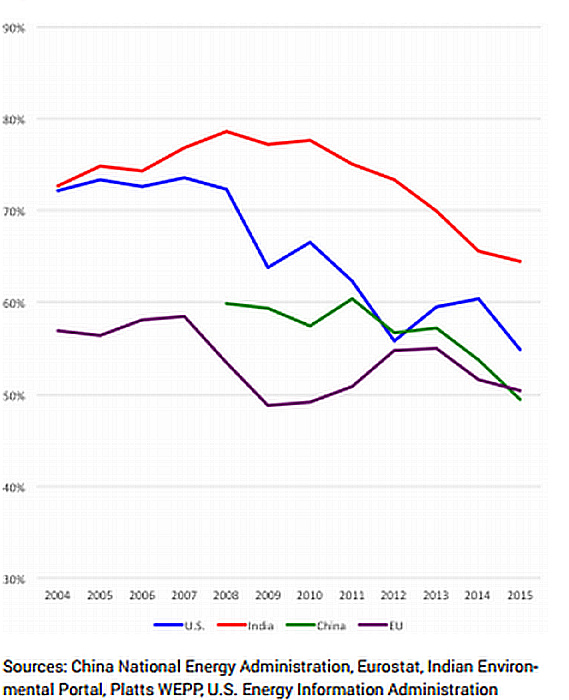

The question is, will all this new coal power capacity be used in the future? The report notes that utilisation rates of coal-fired power plants have gone down in all parts of the world:

Coal/Thermal Power Plant Utilization

It also notes that more and more financial institutions – and governments – are ending financial support for coal power. “Big banks including Citibank, Natixis, and Crédit Agricole are reducing their exposure to or even ending support for coal (…) In June 2013 (…) United States President Barack Obama announced an end to financing for overseas coal-fired power plants in all but the world’s poorest countries when no alternative exists. This was the first in a series of countries and publicly funded financial institutions ending support for overseas coal except in rare circumstances, including the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, and France (…) In June 2015 the Norwegian parliament voted to divest the country’s US$900 billion pension fund, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, from coal. And in September, the US and China issued a joint statement in which China pledged to curb support for carbon-intensive projects along the lines of the US ban.”

“Riding the global momentum, the world’s wealthiest countries—the members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)— agreed in November to limit export credit agency support for coal (…) According to the OECD statement, “Over two-thirds of the coal-fired power projects receiving official export credit support from participants between 2003 and 2013 would not have been eligible for such support under the new rules.” (OECD 2015)

Competitive bidding

According to the report, an estimated $981 billion will be invested in the new coal capacity (under construction and in planning). The authors argue that this more would be better spent on renewables to extend energy access to the poor. They note that “both wind power and photovoltaic (PV) power are now cost-competitive with new coal capacity in most regions. In the United States, new wind power is estimated to cost US$32 per MWh, versus US$65 per MWh for new coal power (Lazard 2015). After competitive bidding in India, multiple contracts for PV power were signed in late 2015 and early 2016 at INR 4,780/MWh or less, the equivalent of US$70–$75/MWh, and fixed flat for 25 years—i.e. equivalent to a 5 percent annual decline in real local currency terms.”

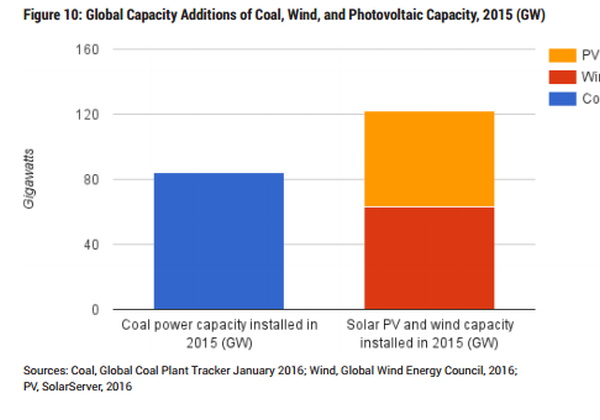

In fact, combined global installations of wind and PV power already exceed installations of coal power. Installations of wind power in 2015 were 63 GW, according to the Global Wind Energy Council (Global Wind Energy Council 2016). Installations of PV in 2015 were 59 GW, according to preliminary figures (SolarServer 2016). In comparison, the Global Coal Plant Tracker identified 84 GW of new coal power capacity in 2015 (these are capacity figures, not production figures: coal-fired power plants have a much higher capacity factor than solar and wind power.):

This article by Karel Beckmann was first published on energypost.eu.

Germany’s No. 5 STEAG considers the closure of several hard coal plants, they are running on 40% only (in German):

http://www.ruhrnachrichten.de/staedte/luenen/Konzern-dementiert-Droht-dem-Luener-Steag-Kraftwerk-die-Abschaltung;art928,2994307

The imminent bankruptcy of Europe’s largest coal company seems to be avoided thanks further subsidies:

http://www.platts.com/latest-news/coal/warsaw/deal-with-unions-paves-way-to-save-polish-coal-26423096

Poland seems to import more and more electricity from Germany:

https://www.energy-charts.de/power.htm

Czech OKD bankrupt:

http://www.mining.com/czech-coal-miner-nwr-verge-collapse-rescue-talks-freeze/

More detailed:

http://www.reuters.com/article/new-world-res-bondholders-idUSL5N17S191

Coal India can’t go bankrupt, nevertheless:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-25/coal-s-drop-forces-indian-monopoly-miner-to-alter-sales-tactic

Vattenfall can’t find a buyer for modern hard coal power plant in Hamburg:

http://www.abendblatt.de/hamburg/article207515043/Vattenfall-Chef-Wir-muessen-Personal-abbauen.html

Machine translation:

https://translate.google.ie/translate?sl=de&tl=en&js=y&prev=_t&hl=en&ie=UTF-8&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.abendblatt.de%2Fhamburg%2Farticle207515043%2FVattenfall-Chef-Wir-muessen-Personal-abbauen.html&edit-text=

7 EU member states are now without coal power:

http://www.climatechangenews.com/2016/04/05/belgium-quits-coal-power-with-langerlo-plant-closure/

——————————————–

This record RE-weekend

https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/topics/-agothem-/Produkt/produkt/76/Agorameter/

idles half of the French atom park, 26 atom power reactors out of 56 are closed or have reduced their output:

http://activites.edf.com/optimisation-et-trading-211255.html

And power prices are near or at record low:

http://www.epexspot.com/en/

[…] – Global coal power: capacity keeps going up, utilisation goes down: […]