Germany’s Energiewende has been driven first and foremost by citizens and communities. Steve Baragona visited a small community threatened by an open-pit coal mine in Eastern Germany and found that the local struggles reflect the broader battle that is currently underway for the future of the German power system.

The Welzow-Sued open-pit coal mine, 70 miles south of Berlin, is one of several in eastern Germany’s Lusatia region. It is expected to expand in the coming years and consume the village of Proschim, just over a mile away. (Photo by Onkel Holz, modified, CC BY-SA 4.0)

When the wind blows just right, Guenter Jurischka can hear the machines that may soon devour his home.

A mile and a quarter from his house in the tiny German village of Proschim, the lip of the Welzow-Sued open-pit coal mine opens onto a 5,000-acre moonscape. A massive steel contraption longer than the World Trade Center towers were tall strips away the earth to expose a seam of lignite coal.

The nearby power plant consumes 20 million tons of this fossilized plant matter each year. The plant’s cooling towers puff clouds of steam on the horizon of the otherwise-pastoral German countryside, 15 miles west of the Polish border.

Swedish energy company Vattenfall plans to expand the mine in the coming years, wiping out Jurischka’s home and the rest of Proschim.

A Proschim native and old-car enthusiast with shoulder-length gray hair, Jurischka has been fighting the mine’s expansion since the village was part of East Germany. And he’s not backing down now.

“I’m not giving up one single brick of my house, one tree of my forest or one square meter of my land,” he said. He is pursuing every legal avenue available. He says he’ll chain himself to the radiator if he has to.

But even with the threat of annihilation looming, Jurischka has mounted solar panels on his roof. He invested in a nearby wind park that generates 15 megawatts of renewable electricity. Another Proschim family built a solar farm and biogas plant down the street that produces another 6 megawatts.

Altogether, Proschim, a tiny hamlet of just a few hundred people, generates enough clean power to supply a city of roughly 33,000. If the mine expands as planned, all of it will go.

As goes Proschim …

Proschim’s predicament in many ways mirrors the planet’s. Renewable energy is no longer a futuristic fantasy. Wind, solar and biogas are making major contributions to how industrialized nations power themselves — and nowhere more so than Germany.

The country is deep into what it calls the Energiewende, translated as “energy transformation.” Financial incentives have brought regular German citizens into the energy industry by the hundreds of thousands. Last year, one-quarter of Germany’s electricity came from renewables. This year, it’s expected to be one-third.

The transition has caught the conventional utility companies by surprise, completely upending their business models. Germany’s big four utilities are hemorrhaging red ink and seeking to reinvent themselves before they go bankrupt. But even so, fossil fuels remain the dominant source of energy in Germany.

The consequences of burning them are closing in. And scientists warn that time to pull back from the brink is running out. With U.N. climate negotiations in Paris coming up and the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan rolling out, experts are looking to Germany’s Energiewende for lessons.

People power

Wolfgang Goltsche doesn’t pay for electricity. He gets paid for it. Twenty-eight solar panels cover the roof of his townhouse in the northern town of Ritterhude, a suburb of Bremen. Three more are mounted on a south-facing wall.

Last year, he used just two-fifths of the energy they produced. The rest flowed out to the neighborhood power lines. And every kilowatt-hour earns Goltsche money. A law passed in 2000 grants him what’s known as a feed-in tariff for the power he delivers to the grid. It adds up to about $40 a month, and it’s guaranteed for 20 years.

Goltsche says he installed the panels mostly out of concern for the environment. But for most people, he added, “if it won’t pay off for them, they won’t do it.”. Clearly, it has paid off.

Since 2000, the amount of renewable energy produced in Germany has more than quadrupled. Last year, renewables were the largest single source of electricity, supplying 40 percent more than hard coal, about 60 percent more than nuclear, and, for the first time ever, slightly more than lignite coal.

The explosion of renewable energy is a mass movement that has completely transformed who produces power. Farmers, neighborhood groups and just plain folks have jumped at the chance to invest in solar, wind and biogas. Citizens own nearly half the nation’s renewable generating capacity.

“Twenty years ago, there were 1,000 electrical generating stations in Germany, and today there are 1.5 million,” said Tilman Schwencke, director of strategy and politics at BDEW, Germany’s energy and water industry association. “It’s a complete revolution.”

“This is one of the bases of why the people are backing up the Energiewende, because everyone knows someone who has invested in renewables,” said Niklas Schinerl, a campaigner with Greenpeace Germany. Polls regularly put public support for the goals of the Energiewende at 80 to 90 percent.

Power disruption

The speed at which renewables captured a third of the German energy market caught just about everyone by surprise.

“Nobody back in 2000 would have believed that that would be possible,” said State Secretary Rainer Baake at the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. Least of all, Germany’s four major utility companies. While German citizens covered their roofs with solar panels, the utilities sank billions into coal- and gas-fired power plants. Now, those look like very bad investments.

So much renewable electricity has flooded the grid that these plants often sit idle. On some sunny, windy days, the price of electricity on the wholesale market is negative — in other words, companies have to pay to get rid of their power. This is not good for business.

“Those conventional utilities that invested five, six years ago in the wrong stuff, they’re wrecked,” said Patrick Graichen, head of the Berlin-based energy think tank Agora Energiewende.

Energy company RWE’s stock has lost roughly three-quarters of its value since the end of 2009. Huge losses led another major, E.ON, to spin off its fossil fuel operations, like amputating a gangrenous limb. Vattenfall is trying to sell its lignite assets. Schinerl said these companies are paying the price for ignoring renewables. “It was always the story, ‘Yeah, in the future we will do that,’ ” he said. “But the future never came for them.” The smallest of the four majors, EnBW, invested most heavily in solar, wind and biogas. The others are now following suit.

“It’s true that we were late,” said RWE spokeswoman Vera Buecke. But now, she added, the company aims to invest 1 billion euros per year in renewables. It is rewriting its business model to increase its focus on grid management and products that increase energy efficiency. All of the majors are searching for new strategies. However, Graichen said, “at this stage it’s not clear who’s going to make it.”

End of ‘people’s Energiewende’?

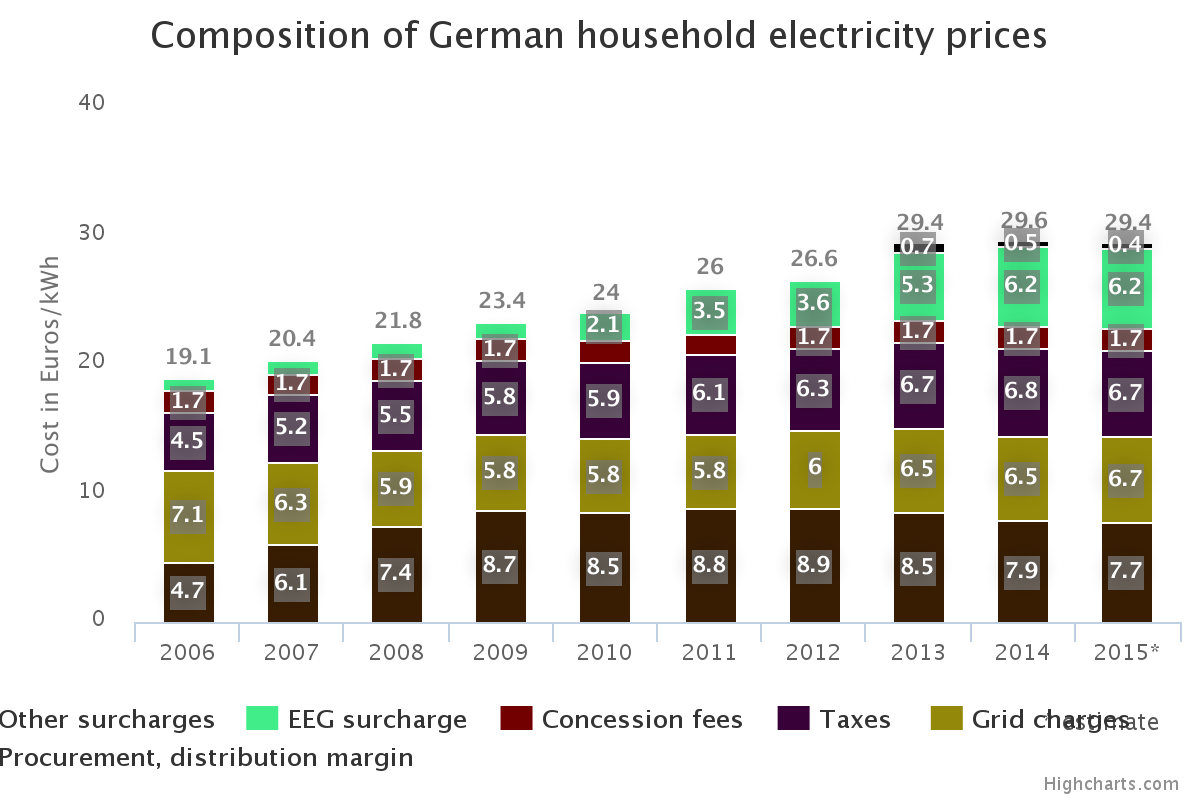

While citizens who invested in renewable energy are reaping the rewards of the Energiewende, the costs are falling on everyone else. Consumers pay for the feed-in tariff through a surcharge on their electric bills. As renewables have ballooned, so has the surcharge. It tripled between 2010 and 2014.

“The surcharge exploded,” Baake said, “and we had to correct that.”. The government has established a system that limits how much renewable capacity is installed each year. And rather than having bureaucrats determine how much investors get paid per kilowatt hour, the government is testing a competitive auction system.

“In the starting phase, [the feed-in tariff] was, I think, the right instrument because we wanted the investors to concentrate on developing technologies,” Baake said. “But now we have to be very clear and say, ‘OK, that was the first phase.’ Now, the renewables are taking over. And we are operating in a market environment. And of course, we want the market forces to work now.”

But some think the new system will push ordinary citizens out of the Energiewende. “It’s too complicated for them to compete,” Goltsche said. “It’s just to rescue the big four [utility companies].”

Not necessarily, Graichen said. Utilities may very well be the top bidders for big projects like offshore wind parks. But citizens’ cooperatives and project developers who work with them have a 15-year head start. And cooperatives are leaner, he added. “I don’t think they’re out of the game,” Graichen said. “I think they’ll concentrate on smaller projects, projects close to the area where the people live,” such as village wind and solar parks.

Setting an example

Back in Proschim, Guenter Jurischka is earning 2,000 euros per month from his village wind-park investment. That’s more than triple his pension. And his solar panels have cut his power bill to essentially zero. But he says that’s not why he did it.

With the coal mine looming, “some of the neighbors think, ‘Is it still worth repainting my house or putting up new wallpaper?’ We wanted to set an example and show everyone, yes, it is. And we are so convinced that we installed this new technology on the roof, even though the house may be torn down in a few years, which we don’t believe,” Jurischka said.

In a way, Jurischka’s example is a scaled-down version of Germany’s. The Energiewende has not come cheap. Germany pays more than 20 billion euros per year in power bill surcharges and other costs to support renewable energy. But as the destructive consequences of climate change are coming into view, experts are asking whether the world will make the investments necessary to avoid the worst.

If not, they say, Jurischka’s home will not be the only one lost to fossil fuels.

This article was first published on Voice of America and is republished with permission by the author. Steve Baragona (@stevebaragona) is an award-winning multimedia journalist covering science, environment and health. He spent eight years in molecular biology and infectious disease research before deciding that writing about science was more fun than doing it. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a master’s degree in journalism in 2002. Baragona co-wrote a documentary on the impacts of the 2012 drought in the U.S. Midwest that won four awards.