Foreign onlookers are interested to know what lessons can be learned from Germany’s energy transition. In a recent article, a German energy sector executive drew conclusions for the outside world themselves. Craig Morris can’t follow the logic.

“In Germany right now, you see a market distorted by political changes, unpredictable changes” – really? (Photo by David Iliff, modified, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On a visit to Australia, Volker Beckers – former CEO of RWE npower, the German firm’s UK-based gas and power provider – spoke about what folks Down Under should learn from the German Energiewende. Asking RWE what it thinks about the energy transition is a bit like asking Volkswagen what it thinks about emissions tests – but okay, Mr. Beckers, you have my attention.

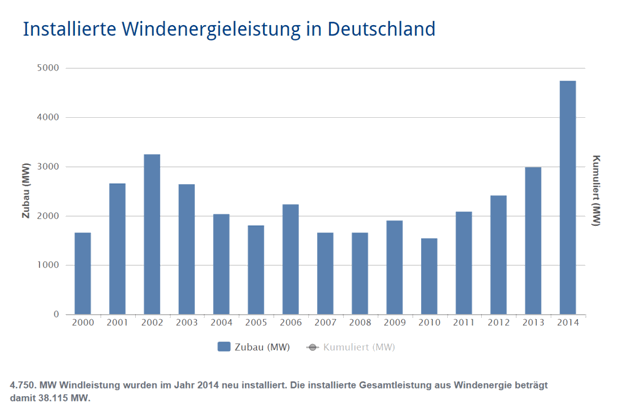

“In Germany right now, you see a market distorted by political changes, unpredictable changes” – really? Though the word “nuclear” never appears in the text, the only back-and-forth Germany has had in energy policy pertains to the phaseout. As I have written before, there has been an impressive amount of continuity in policies for solar, biomass, and wind power. This is what annual wind turbine installations look like in Germany – some ups and downs, but a fairly sustained market:

Source: BWE

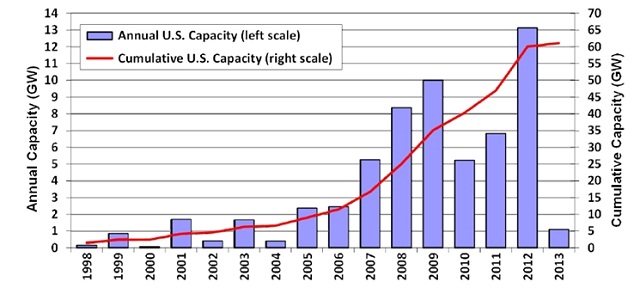

Look for a similar chart for the US, and it’s hard to find. It’s not on the Wikipedia site for wind power in the US at all. The chart above is from German Wind Energy Association BWE. I could not find any such chart from the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) website, though it may be in this $ 550 PDF. US wind power supporters like to avoid presenting this information because it looks like this:

Source: US Department of Energy

Yes, the US market collapsed from 13 GW down to 1 GW from 2012-2013, a fact that this article did not even find worthy of mentioning – nor does the original US Department of Energy study explicitly underscore the US’s stop-and-go market, instead speaking only vaguely of “federal policy uncertainty” (PDF). Look back at the period from 1998-2005, and you see that the US wind power policy has often been unreliable from one year to the next. Germany’s hasn’t.

“Retroactive change has led to investors leaving the [German] market,” Beckers told his Australian audience. Germany has never had any retroactive changes to renewable energy policy, as I repeatedly explained during the wave of retroactive amendments to solar policies throughout Europe. So I’m with Angel Gurría, Secretary-General of the OECD, here:

“What is noteworthy about Germany’s approach is that it has been more sustained and consistent than that of many other countries, which have been forced into complete U-turns in their energy transformation by pursuing needlessly costly policies.”

In contrast, nuclear policy has been retroactively changed in Germany – thanks partly to RWE’s lobbying. In 2000, RWE and other owners of nuclear reactors signed an agreement to shut down their plants after around 32 years of service, but these firms pushed hard to have that agreement nullified in 2009-2010. Too bad Fukushima happened less than six months after the new deal had been made. Had RWE stuck to the original phase-out agreement, it might have less to regret now. The big study that has yet to be written is on what the power market would look like today with the longer reactor service lives from 2010. With more baseload generation capacity on the market, wholesale prices would be lower, and RWE might have been hurt the most as the country’s biggest lignite firm. So instead of complaining, RWE should be happy that Merkel shut down so much nuclear in 2011 – its competitor E.on suffered more.

Beckers reveals what he really wants in the following: “The best environment should be a consistent and coherent market framework and a robust emissions trading scheme.” A provider of fossil energy that calls for emissions trading basically says: do away with renewable energy policy altogether so we can focus our lobbying against strong emissions regulations. Under the leadership of Beckers, RWE npower lobbied hard against stricter emission standards. In 2013, RWE called the EU’s ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme) “well-established and fully functional” (PDF). In other words, the firm is happy with a uselessly low carbon price.

So what should we do? “The rhetoric in big companies has seen consumers change from ‘client’ to ‘customer’ to ‘service customer’. But this was just a change of rhetoric,” Beckers says, adding that these “big companies” should instead “ask what the consumer wants, and work from there.”

I’m with Toni Morrison: citizens should not be called consumers. The energy sector should ban the word “consumer” from its vocabulary altogether; people are becoming “prosumers,” increasingly making their own energy as well as consuming it. As citizens, they have a right to do so. In fact, we should not even be asking what big companies need to do. We should ask what citizens and society need – and what role big companies can then play… if they have a role to play.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

It has taken the big four a lot of time to realize that the earth is no longer flat (and that their attitude to renewables was out-dated. Just consider the quotes.

Eon-Chef Teyssen 4.6.2008 (dpa):

E.ON habe wie Don Quichote gegen die Windkraft gekämpft. “Das war falsch, das korrigieren wir.” Es werde dem Konzern aber nicht noch einmal passieren, dass er vor “lauter Besserwisserei„ einen derartigen Fehler mache.

[EOn fought against wind energy like Don Quichote. This was wrong and we will correct this. It will not happen again, that by presuming superior knowledge, this company will make such a mistake.]

RWE Chef Terium 6.3.2014 (Zeit):

„Wir sind spät in die Erneuerbaren Energien eingestiegen – vielleicht zu spät.“

[Our entry into renewables came late, perhaps too late.]

A remarkable admission by Teyssen, but has it really alterted EOn’s approach or business model? Can a centralized giant really get into an energy that is by nature decentralized?

It has taken RWE another six years to draw a similar conclusion. Too late? “‘Tis a consummation devoutly to be wished.” So let us hope the best for them.

It is well to remember that both companies kept telling us, the policy makers, and the public, that they were the experts in the field – and we, pushing for more renewables, had our heads in the clouds (and this is just the polite version).

And in some respects they still are telling that story – or a greenwashed version of it, these days. They are the undead … But then: we all know what happened to the dinosaurs …

And if one day, we accept full cost calculation in the energy markets, they are dead as doornails. For they cannot compete, as we now know, in a fair, full cost market. And perhaps the quotes reveal that in lucid moments, their CEOs know this.

Data on U.S. renewables are not as easy to find as they should be, but you can get much of what you want in reports from the Electricity Markets and Policy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, a DOE-funded lab.

https://emp.lbl.gov/reports

They give away their reports and their data in the form of spreadsheets for free. They have the best freely-available data that I know of on (mostly utility scale) US wind and solar.