The news has hardly been reported in English yet, but the new conservative governing coalition elected in Denmark this summer plans to abandon the country’s ambitious targets for a carbon-free economy. The move could provide a precedent for Germany. Craig Morris reports.

Is Copenhagen abandoning Denmark’s climate goals? (Photo by Alyson Hurt (https://www.flickr.com/photos/alykat/), modified, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This month, I have focused on the pushback against renewable energy growth in Spain and Italy along with the UK. Now, it seems that Denmark is teetering as well.

One of the few reports in English on the matter was published at the beginning of September by Bloomberg. In an interview on a wide range of topics, the new Danish Finance Minister Claus Hjort Frederiksen says the new government aims to abandon the country’s targets for renewable energy. Denmark has a target of 100 percent renewable energy (not just electricity) by 2050. The plan was first published in English in March 2012, but has since been taken off-line.

At present, we lack details. Bloomberg believes that the target for 2050 will be reviewed critically and that Denmark will “drop plans to phase out coal-fired power plants.” In contrast, a report on the situation in Denmark from Sweden (in Swedish) says that coal and gas plants scheduled to be decommissioned between 2030 and 2035 are to be allowed to stay in operation longer. However, the Swedish paper reports that the 2050 target is not in question.

In August, Denmark’s new Climate Minister was also quoted saying that a 40 percent carbon reduction by 2020 would be “too expensive for Danish businesses” – an unusual comment from a Climate Minister. One would expect such things from the Economics or Industry Minister. Apparently, there is widespread agreement throughout the new coalition.

The news is interesting from the German perspective because Denmark’s move opens up a door – or should I say an escape hatch. Denmark is likely to achieve a 37 percent reduction from 1990 in CO2 emissions by 2020 (the official goal is 40 percent). Germany has the same target of a 40 percent reduction and is likely to fall short by a similar amount.

Finance Minister Frederiksen’s reasoning is telling: He says that Denmark will continue to fulfill all international agreements for carbon emission reductions. But he calls the goal of 100 percent renewables by 2050 and the 40 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2020 “national targets.” The level that Denmark is obligated to achieve within the EU is lower; these more ambitious targets are voluntary. In other words, Denmark is free to step away from them.

So is Germany. The 40 percent target stems from the government’s Energy Concept of 2013. As German energy policy expert Oliver Geden reminds us (in German), that goal is “legally nonbinding.” The 2007 “Energy Framework” proposal (PDF in German), which became law in 2010, specifically calls the 40 percent CO2 reduction target “voluntary” (Selbstverpflichtung). Page 134 of the Monitoring Report from 2012 (PDF in German) explains that Germany’s obligations under the emissions trading platform (EU-ETS) and Effort Sharing (the areas not covered by the ETS, such as cars, agriculture, and buildings) only add up to “around a 33 percent reduction.”

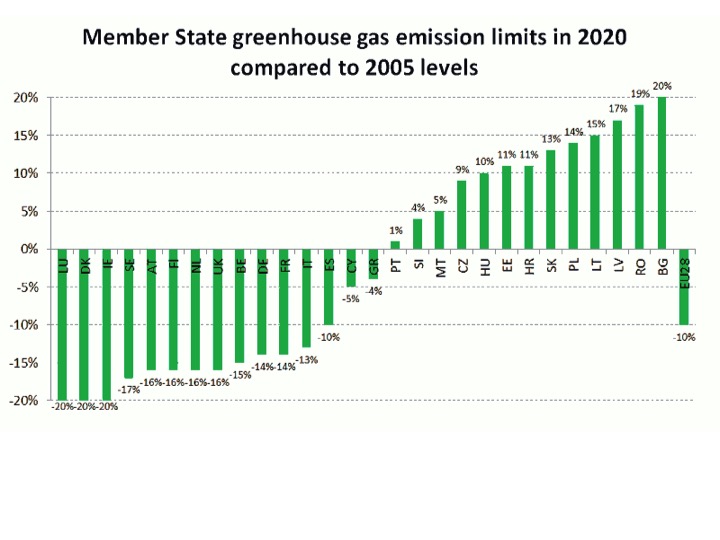

The EU-ETS covers nearly half of emissions in the EU. While member states do have emission allowances, these levels are not ceilings; the whole point of the emissions trading platform is to trade between participants across international borders. The overall EU-ETS target for 2020 is a 21 percent carbon reduction (relative to 2005, not 1990).

“Effort sharing” covers the rest. The German target sets a 14 percent reduction – but again, relative to 2005, not 1990. Now, you have to know what German carbon reductions were between 1990 and 2005: around 17 percent. It does not add up to 40 percent. But there is also no single internationally binding number for Germany.

Source: EU

In other words, the German government has unilaterally decided to go for a 40 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2020 although it is “only” legally obligated to achieve a 30-35 percent reduction, according to expert estimates. The news from Denmark is therefore all the more disconcerting. If the Danes go through with their plans, German policymakers will be able to point to the Danish precedent and say, see, we also fulfilled our international obligations. The rest will be called a regrettable inability to reach voluntary targets. Aside from considerable international embarrassment, there will be no other penalties.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

Black Sabbath is playin’ in Copenhagen – so the black power can’t be switched off until then:

http://cphpost.dk/news/black-sabbath-coming-to-denmark.html

And b.) there is already enough power in the Danish grid to gag and then send the UK utilities to hell:

http://cphpost.dk/news/denmark-laying-energy-cable-to-the-uk.html

Governments come and go, the people do what they want anyhow.

Germany’s strange coalition tried to kill private PV and lost the race, the numbers of PV installations are on the rise again:

(in German)

http://www.iwr.de/news.php?id=29794

http://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/cln_1431/DE/Sachgebiete/ElektrizitaetundGas/Unternehmen_Institutionen/ErneuerbareEnergien/Photovoltaik/DatenMeldgn_EEG-VergSaetze/DatenMeldgn_EEG_VergSaetze.html

The Danish government is a right wing minority government with only the party Venstre (directly translated – Left) but they are more or less comparable to their friend party in the US, the democratic party. The conservative party is against proposed change and so are the two major industry organizations.

The Danish carbon footprint in electricity production has already dropped more than 40% relative to the emissions in 1990 despite population growth and economic growth.

In hindsight, the 2007 “Energy Framework” paper appears to confirm the deficient methodology employed by governments in appraising future CO2 reductions. This treatment mentions nuclear energy only once, although at that time 22% of Germany’s electricity was being generated by the country’s 17 nuclear reactors. By contrast, the Energy Framework paper contains 17 references to carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology that was unproven at the time and which no longer qualifies as a CO2 abatement option. In consequence, renewable energy expansion in Germany has been dedicated primarily to achieving the CO2 reductions that these technologies cannot deliver. The country’s 40% greenhouse gas reduction goal by 2020 has since been rendered more difficult to achieve by Vattenfall’s impending sale of 35% of the country’s lignite generation capacity. Presumably the new owner will not be taking over these eastern German power plants simply to retire them, but instead to continue their operation as long as possible for recovering his investment. There have been few commentaries on this development, which credibly illustrates the limited means available to governments for fulfilling the CO2 reduction goals that they themselves have declared.

‘Germany’s strange coalition tried to kill private PV and lost the race, the numbers of PV installations are on the rise again’

They may be on the rise, but German pv globally generates at 10% capacity factor as a yearly average, and a ridiculous 3% for the 4 entire months between November and February.

Pv is useless, especially in Germany, a country with little sunshine.