In 2014, installations of new photovoltaic arrays in Germany fell to almost a quarter of the level sustained from 2010 to 2012. Craig Morris says the performance nonetheless remains impressive relative to the size of the German grid.

For new PV installations to be profitable, owners have to look for creative solutions like direct consumption in Germany. (Photo by Kauk0r, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The German solar sector is caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, it puts pressure on politicians by complaining that the market fell from around 7.5 GW of newly installed capacity in 2012 to just under 2.0 GW last year, according to preliminary figures (press release in German). But if its representatives protest loudly that recent policy changes now make PV a bad investment, the sound bite that reaches the public will be “don’t build PV.”

Let’s take a step back. Germany now has a target corridor of 2.4 – 2.6 GW annually for newly installed PV. If more is built, future feed-in tariffs drop faster; if less is built, the monthly reductions shrink. Note that these changes would only affect new arrays, not existing ones retroactively.

Because the market did not grow as fast as desired, feed-in tariffs for new PV will fall by only 0.25 percent per month from January to March this year. Each quarter, progress is reviewed, and future feed-in tariffs are adjusted accordingly.

But the level of feed-in tariffs is increasingly of marginal importance anyway. At present, the rates paid range from just under 13 cents per kilowatt-hour for the smallest roof arrays to roughly 8.7 cents for a raise up to 500 kilowatts (spreadsheet in German). In contrast, the retail rate – which owners of small arrays are likely to pay – is around 29 cents, while the rate for midsize businesses – which owners of the larger PV category are likely to pay – can be as high as 15 cents. In other words, the best returns may come from offsetting power from the grid with solar power from your own roof.

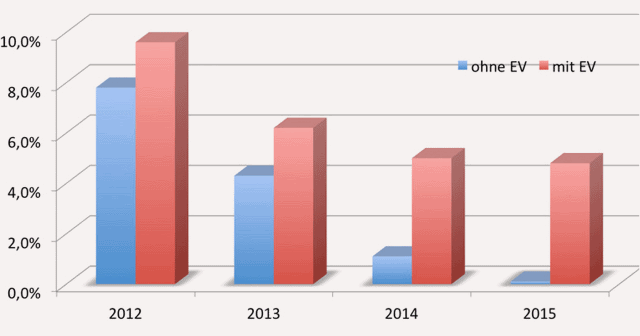

Unfortunately, this calculation is not so straightforward. Berlin-based consulting firm Solarpraxis took a stab at the math in a report entitled (in German) “photovoltaics is still a good investment.” In the chart below, “ohne EV” stands for “without direct consumption,” meaning that only the average return from feed-in tariffs is indicated. Likewise, “mit EV” means that direct consumption (offsetting higher retail rates with solar power) is included.

Source: Solarpraxis

The use of a 3-D graphic makes it unnecessarily difficult to specify what the actual numbers are (note to Solarpraxis: 3-D graphics are almost always bad), but we see from the German text that the return on PV without direct consumption fell from 7.8 percent (as the text explains) to only 0.1 percent today. With direct consumption, the return is still 4.8 percent, much more than the average person could get from any other low-risk investment.

But even this representation is a generalization. Under net-metering in the US, your power meter simply runs backwards when you produce more solar power than is consumed on-site. But in Germany, “direct consumption” (Eigenverbrauch or EV in the chart) means that the power has to be either consumed immediately or stored locally without ever touching the grid. If you work from home or if your family is at least home for lunch, your power consumption might be relatively high when your array will generate most of its electricity. If not, your level of “direct consumption” may be quite low without battery storage – and the more batteries you have to buy, the lower the return on your investment.

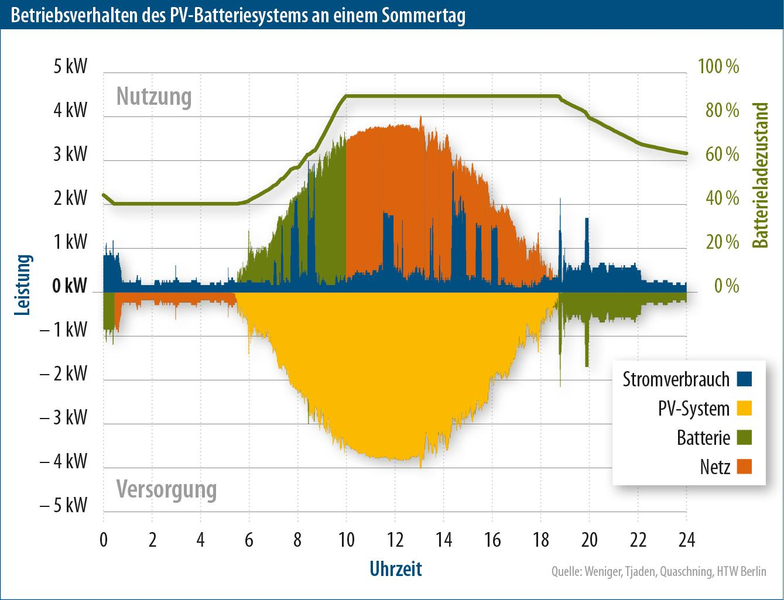

The Solarpraxis article puts the level of direct consumption for the average German household at a measly 5-10 percent without battery storage. The chart below illustrates the challenge quite well. The blue area represents the household’s power consumption level. The yellow area below the baseline shows us how much solar power is generated, and when that area is flipped up above the baseline we see how poorly it matches power consumption. The green area above the baseline thus represents solar power in excess of consumption; it goes into battery storage. By around 10 AM, the batteries are full, so the orange area represents solar power sold to the grid and paid for with feed-in tariffs.

Source: Solarpraxis, and background article in German

Back below the baseline, we see that the home begins consuming power stored in the batteries that morning (green area). That electricity is used up by 1 AM, so the house runs on power from the grid for the next five hours until around 6 AM. Note that this home produces far more solar power than it consumes electricity, yet it is dependent upon the grid both for consumption and sales of excess power – even with battery storage. Only 30% of solar power is directly consumed over the day, as the German article (PV Magazine) explains. Note as well that the battery pack’s state of charge (Batteriezustand in green on the right). We might expect (from our cell phones and laptops, for instance) such batteries to charge and discharge from 0 to 100 percent, but as anyone who has driven a hybrid car knows, large battery systems prefer to stay within 40 to 90 percent in order to extend battery life.

Solar arrays are thus currently unattractive with feed-in tariffs, but the calculation of the return including “direct consumption” is not for the fainthearted – it has to be done on a case-by-case basis and requires some expertise. Hence the shrinking of Germany’s PV market.

Still, Germans remain committed to solar. With peak power demand only a tenth of the US level, the measly 2.0 GW in 2014 is equivalent to 20 GW in the US. Americans have yet to reach the level Germany just crashed down to.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.