Regular readers of this blog have a good overview of how North America and the UK view Germany’s energy transition, but what do emerging economies think? The Konrad Adenauer Foundation has taken some comprehensive surveys. Craig Morris investigates.

The German Energiewende’s success isn’t its domestic impact, but being an international leader that proofs that a swift transition to renewables is viable. (Photo by GovernmentZA, CC BY-ND 2.0)

In Germany, major political parties have political think tanks. Their role is partly to engage in a debate with civil society and other stakeholders outside politics. In foreign countries, the think tanks cooperate more closely than at home in order to present a more unified (and dignified) picture of what Germany stands for than could be provided by a translation of domestic party politics. (As an American, I sometimes cringe when I see unadulterated US political bickering reach foreign shores.)

This blog is funded by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, the think tank of the German Greens. The think tank of the Left Party – the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation – has done little work in English on the Energiewende, but I reviewed one of their German publications here. The Social Democrats (SPD) are behind the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, which published an interesting recent study entitled “Towards a global energy transformation,” (PDF) which we will have to come back to another time.

The Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS), the think tank of the Christian Democrat Union (CDU – the party of Chancellor Merkel), has been busy communicating the Energiewende abroad. A publication released at the end of September shows that the work done by the KAS is a good complement to the Energiewende project you are now reading. Though the recent PDF is currently only available in German, the previous study was translated into English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. Both studies summarize the findings of surveys taken in these partner countries: in the recent publication, Russia and India; in the previous one, Brazil, China, and South Africa. In other words, the KAS surveys the BRICS countries.

Even if you are not fluent in German, however, the statements made by the survey participants in the new study are still accessible in English until KAS (hopefully) produces translations; you simply will not be able to read the surrounding analysis.

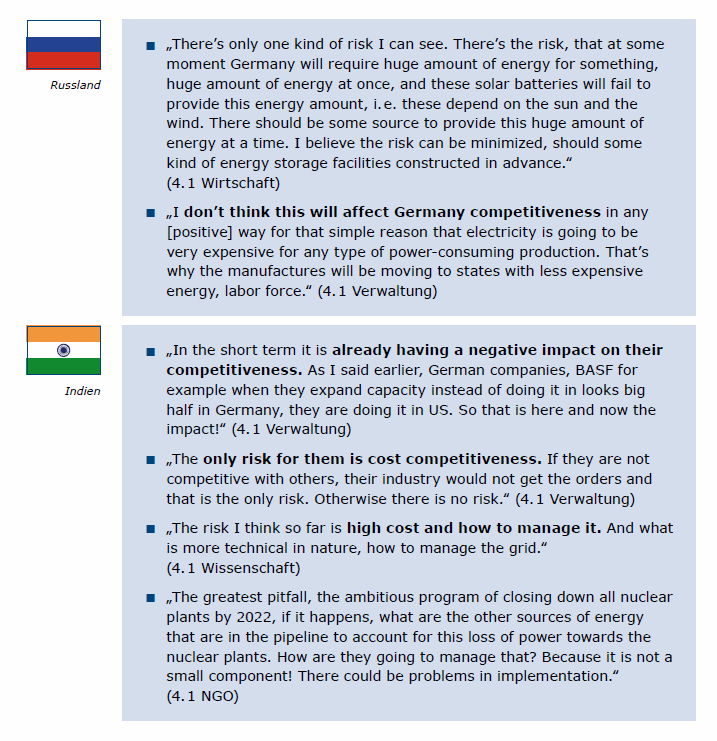

An example of some critiques from the survey. Source: KAS.

One fascinating find in the current study is that India and Russia view the Energiewende a bit differently. Indeed, the KAS finds that Russia is a special case as a global provider of fossil energy; there is greater overlapping between India, Brazil, China, and South Africa.

“One critical issue is energy security,” says Christian Hübner, who oversaw the two studies for the KAS. “I personally see the energy transition as a major way of increasing German energy security in the long run.” Indeed, this aspect probably deserves more recognition in this blog as well.

Here, Russia’s special case becomes clear. The survey found that, while Russia views Germany’s energy transition as a logical step to be expected, there is nonetheless concern about losing Germany as a strong buyer.

On the other hand, the survey found that both Russia and India aim to use German technology to modernize and diversify their own energy supply. Here, it is worth mentioning that technological leadership was always a goal of the Energiewende; Germany aimed to be a first mover all along. In the solar sector, that’s looking better than you might expect. And both the biomass and wind sectors export roughly 2/3 of production.

The surveys also asked what the partner countries think the downside of the Energiewende is, and the main things mentioned are the high cost (particularly for retail power), the intermittency of wind and solar, and the nuclear phaseout. Interestingly, there are also some comments about internationality – but not the usual complaint that Germany is going it alone. Rather, a few responses indicate that Germany cannot solve the world’s problems on its own, so it needs to convince the rest of the developed world to undertake an energy transition.

I cannot do justice to the roughly 170 pages in both documents in a single post, so do check them out for yourself. Overall, if you browse through the survey responses in both overviews, you see that opinions among decision-makers are more positive than a lot of the press reports about the Energiewende. Terms like courage, world leader, competitive, and independence pop up in various answers to different questions. For someone like me steeped in (mis)reports in the Anglo press, I frankly found these expert responses to be a relief.

One respondent from Russia perhaps put it best: “entire humanity is going to benefit from what Germans will definitely develop.”

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.