A new study by Fraunhofer IWES investigates how much natural gas could be offset by renewables and efficiency, and one graphic indicates the implicit message that the energy transition could make Germany independent of gas imports from Russia by 2030. Craig Morris investigates.

Heat image of an apartment building – energy efficiency in the housing stock will play a big role if Germany wants to achieve partial or total independence of foreign gas. (Photo by Martin Abegglen, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Germany is phasing out nuclear, with the last plant to go off-line in 2022. As we showed in our recent paper German Coal Conundrum, renewables have filled that gap easily since 2011 and should be able to continue to do so by the end of the phaseout. Nonetheless, Germany imports a lot of natural gas – around 90 percent of consumption, 38.7 percent of which was from Russia in 2013. There are now also calls for a coal phaseout, with natural gas being the intended benefactor. Not only is natural gas less carbon-intensive than coal, but gas turbines also provide the backup flexibility that wind and solar power need.

Too bad tensions are now rising between Russia and the EU. We now face energy security concerns that make the call for a transition from coal to gas politically problematic. Along with the nuclear phaseout and the call for less coal, we now have the call for greater energy independence from Russia.

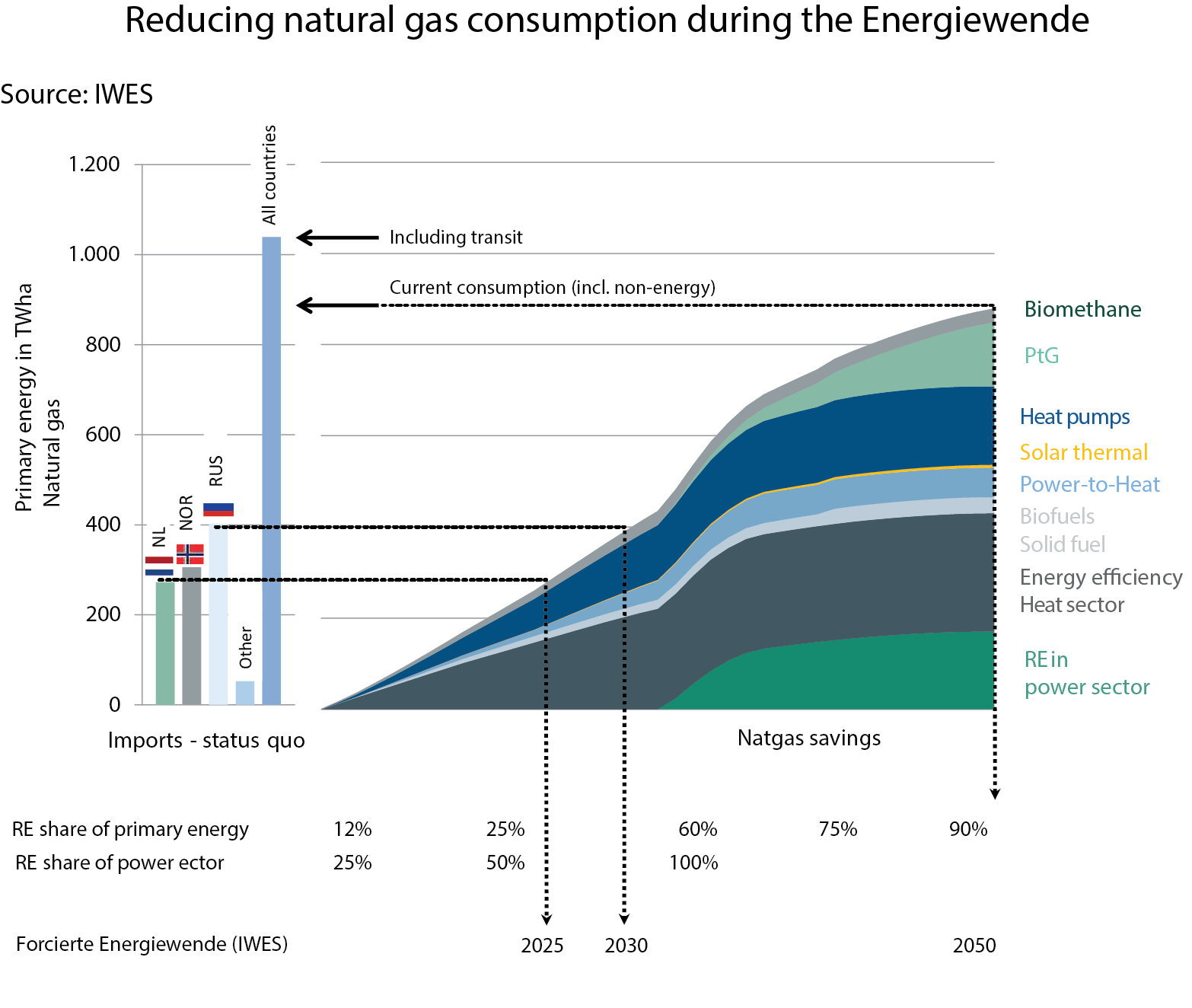

Roughly 315 TWh of gas was imported to Germany from Russia last year. The study finds that Germany could offset that amount by 2030 during the Energiewende if the other imports are left untouched. During that time, however, production in – and hence exports from – the Netherlands and Norway are expected to taper off. There seems to be no short-term solution source: IWES

Now, researchers at Fraunhofer IWES have investigated a likely outcome in the energy transition up to 2030 (PDF in German). Their main contention is that we continue to focus too much on the power sector. Most natural gas in Germany is consumed for heat applications, with nearly 50 percent of German domestic heat being fired with natural gas.

The mistake is common. In a recent article, the Economist wrote “the amount of energy generated from gas has fallen sharply” in Germany, but by “energy” they mean only electricity.

We see what the difference is between heat and power when we compare a few numbers. In 2013, Germany consumed around 900 TWh of natural gas, roughly 814 TWh of which was imported – around 90 percent. But both of those numbers are larger than the country’s entire power consumption at around 600 TWh. Clearly, gas consumption is bigger than the entire power sector.

The researchers therefore expanded the focus to cover not only power, but also heat and transport. But with so little natural gas being used in vehicles, the obvious culprit is heat. By 2025, building retrofits – Passive House – would reduce demand for natural gas by around 110 TWh. The potential of heat from biomass – including consideration of ecological sustainability – is also expected to be able to offset around 15 TWh of natural gas by 2025. Another 75 TWh of natural gas could be offset by using heat pumps. Power-to-heat (excess electricity stored as heat) could offset an additional 17 TWh by then as well. Interestingly, the researchers only expect solar thermal to offset a single TWh by that time. These measures would result in an overall offset of gas by 217 TWh by 2025.

In total, the study thus finds that alternative heat sources could offset a total of 108 TWh along with the 110 TWh production from building retrofits. In contrast, gas consumption will not be reduced in the power sector before 2030 because the focus will be on lowering coal consumption after the nuclear phaseout (the opposite of what is happening now).

In other words, Germany will mainly have to reduce natural gas imports outside the power sector. The study also finds that, starting in around 2030, other options – particularly power-to-gas and methanation – will become feasible, so there is far more potential to substitute natural gas by 2050.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

Over the years you’ve repeatedly pointed out there’s too much of a focus on power and too little on heat. It seems to me you’re making a half-way argument because we can easily get heat from power. Are you saying we should recognize a cornucopia of ways to get heat?

> Not only is natural gas less carbon-intensive than coal …

There was one single article at telepolis.de, a couple of months ago, that mentioned leaks on the way from the natural gas fields to the final consumer of an amount of 7 percent by conventional production and 14 percent by production by fracking. These numbers sound more or less believable. (Electricity – although being something totally different from gas – “suffers” also from a loss of about 7 percent from the power plants to the consumers.)

If we assume that natural gas consists mainly of methane and consider that this gas has a greenhouse effect that is 25 times higher than that of CO2 then natural gas production leads to 1.75 … 3.50 amounts CO2 for 1 produced amount natural gas. How much CO2 results from burning 1 amount coal? 2.68 for stone coal and 3.25 for brown coal.

So, is natural gas really the ecologically superior energy source?

Stephan, your comment and question seem right on the mark. Gas here in the U.S. is assumed to emit 450 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour, by the Energy Information Administration. This is an old figure that has not been updated with the deterioration of our old gas wells or with the coming of fracking. It is an academic figure the U.S. EIA is derelict in relying upon. The EIA says coal is at about 1000 grams. But if, as you say, the methane losses are high enough, gas surpasses coal.

If we make CCS mandatory at COP21, heating can also be made climate neutral, without waiting on more power from wind.

It will be more expensive than cheap russian gas.

But heat from coal, via clean power plants, also comes with freedom to say STOP to Putin, when he grabs the next piece of just across the border land.

Because CCS is now BAT, and with Olivine, it also does not harm coal to power efficiency, we should reconsider natural gas for decentral use without CCS.