Everyone seems to agree that the renewables surcharge in Germany is a bad indicator of the cost of the country’s energy transition. Today, Craig Morris proposes a solution to the communications problem.

Calculating the different components of the renewables surcharge isn’t as trivial as it seems – differing interpretations are used by political actors for their purposes. (Gabi Eder / pixelio.de)

The renewables surcharge and feed-in tariffs are two sides of the same coin. The latter are paid to producers of renewable electricity; the former is the cost of those payments minus revenue from the sale of the power on the power exchange. In other words, the surcharge covers the remainder of feed-in tariffs payments minus the sale of that power.

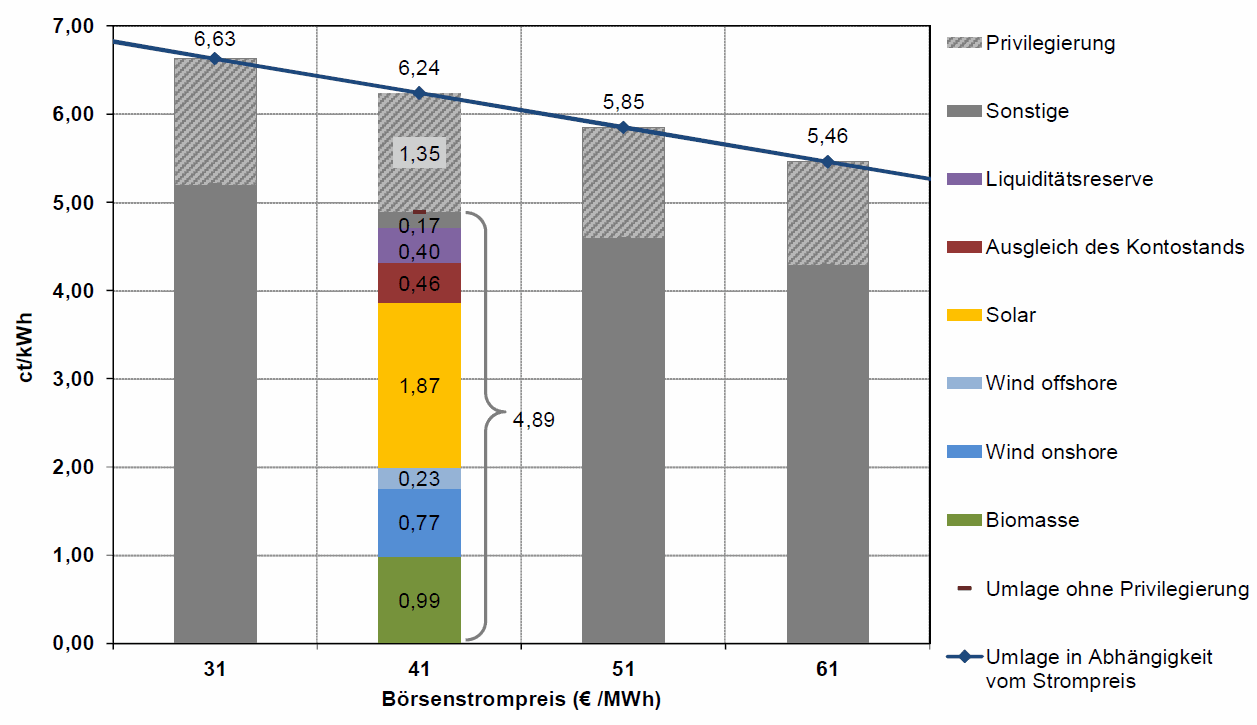

The surcharge has a number of components, however, not all of which are directly related to the cost of green energy. Take a look at this chart, for instance:

Source: Öko-Institut

Here, the researchers are focusing on the effect of wholesale prices on the power exchange. The chart illustrates well how the surcharge increases as wholesale prices decrease. This year, the surcharge is 6.24 cents per kilowatt-hour based on a wholesale price of 41 euros per megawatt-hour (equivalent to 4.1 cents per kilowatt-hour). But if that wholesale price rises, the surcharge sinks – because the renewable power paid for with feed-in tariffs could be sold at higher prices, so the remainder is smaller.

The colors show a breakdown of the cost components by power source, and you can read those items in the legend without a translation. But four of the items might trip you up: Sonstige is Other; Priviligierung is industry’s share passed on to SMEs and retail ratepayers; and then there are the liquidity reserve (purple) and the carry-forwards (red). The former is provisions set aside for a potential future overdraw; the latter, the overdraw from the previous year. But as I wrote in January, the account is in the black now, so both of these items – collectively worth 0.86 cents above – could/should disappear in the surcharge next year.

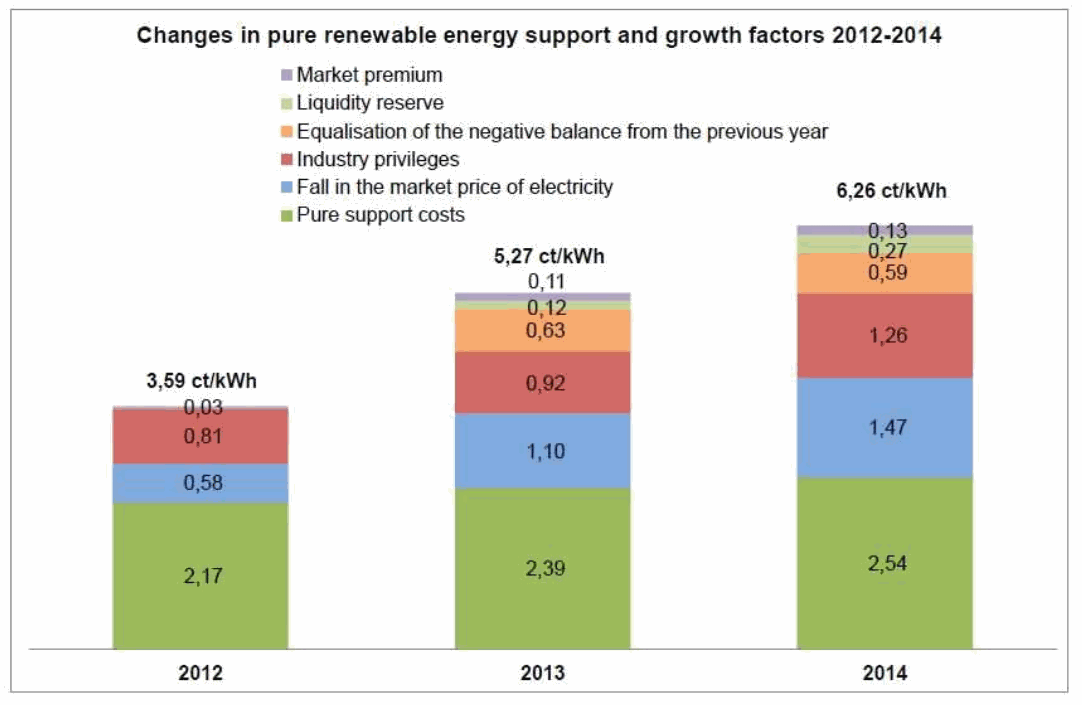

That article from January includes another way of looking at the surcharge:

Source: BEE

Don’t ask me why the organization has a slightly incorrect figure for 2014 (6.26 instead of 6.24 cents); I notified them at the time, but I can find no corrected version. Strangely, the breakdown of the set-asides is different, though the final amount is the same: 0.86 cents. But I actually want to focus on something else.

This chart has the effect of wholesale prices indicated as a separate item. The actual payments of feed-in tariffs divided by the amount of power covered by those payments produces 2.54 cents per kilowatt-hour. The shortfall from power sales on the exchange bring us up to 3.97. This level is the same in the first chart above once industry privileges, Other, and the two items for provisions are taken out.

In other words, the actual renewables surcharge is around four cents per kilowatt-hour.

It would help people understand the discussion if we spoke of the surcharge at that level, which reflects the cost of renewable electricity including its impact on wholesale prices. We could then say that retail consumers pay more than 150 percent of that surcharge, whereas an industrial firm that pays, say, two cents on average would only be paying 50 percent of the surcharge – the cross-subsidization is quite clear then.

Last year, Felix Matthes of the Öko-Institut – the same organization that made the first chart above – complained that the renewable surcharge is not a good indicator of the Energiewende’s true cost. My proposal won’t change what people pay, but it will help everyone understand the true cost better.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.