Germany set a new record on Sunday, May 11, by getting nearly three quarters of its electricity from renewable sources during a midday peak. Nonetheless, Craig Morris says the resulting negative prices are both good news and bad news.

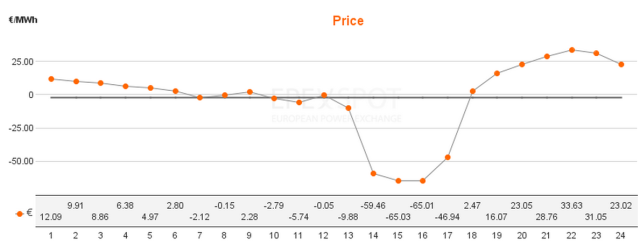

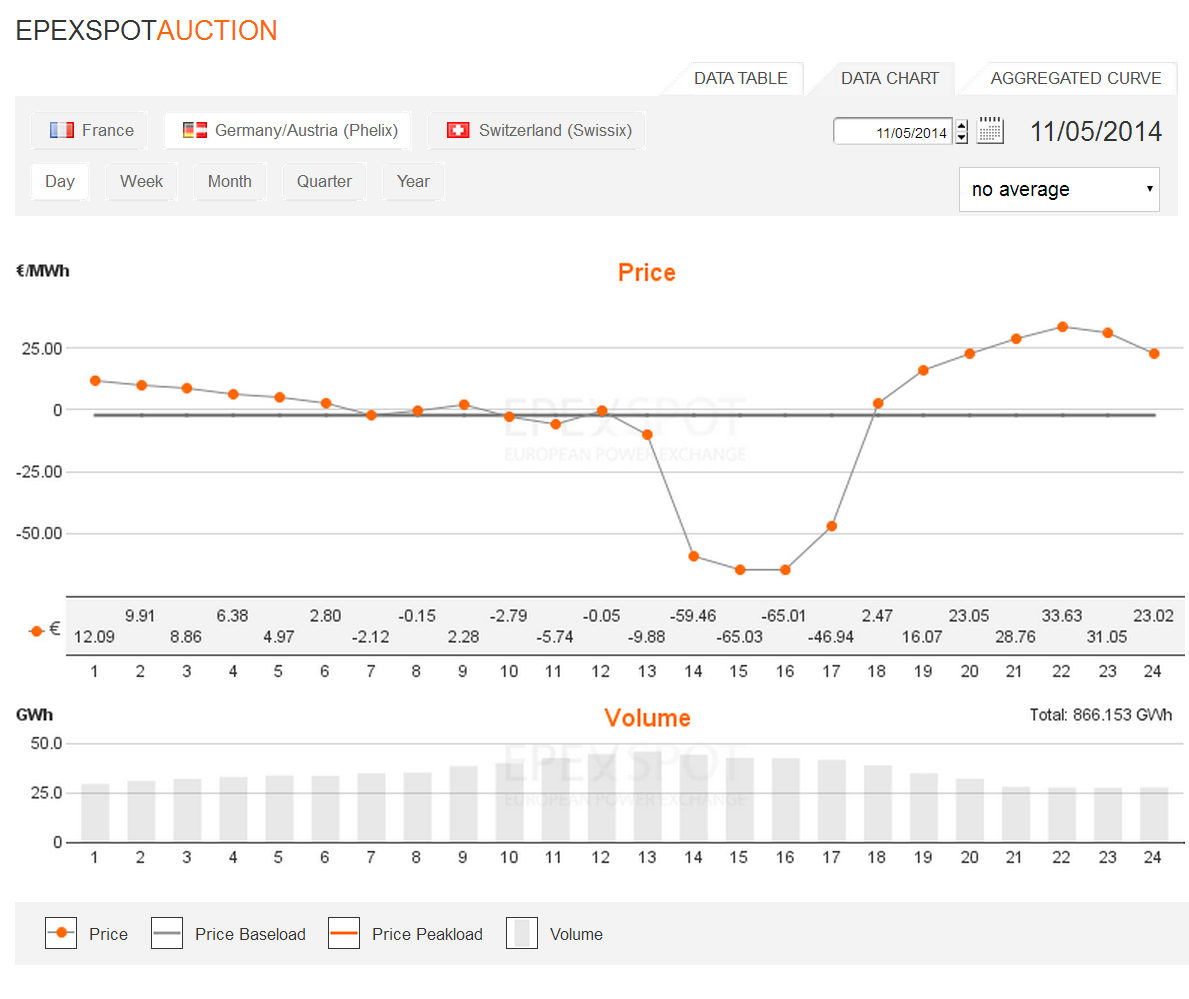

On May 11th, power prices were negative for several hours in Germany. (Source: EPEX)

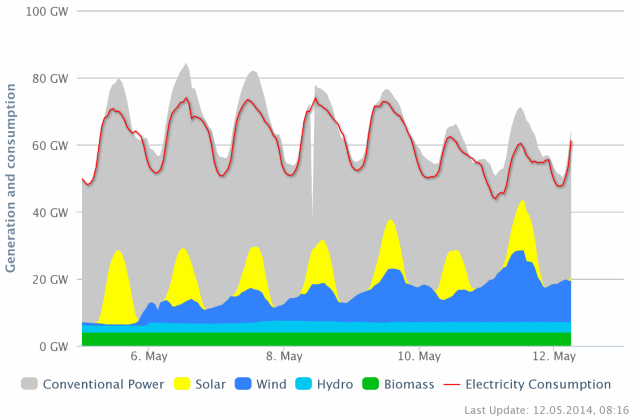

Wind power peaked at around 21.3 GW at 1 PM on Sunday, with solar simultaneously coming in at 15.2 GW. Add in the roughly 3.1 GW of hydropower and 3.7 GW of electricity from biomass that Germany usually has, and the output of conventional power plants was pushed down to 26 GW at 1 PM on Sunday.

Power demand, however, was only at 59.2 GW, meaning that only 15.9 GW of conventional power was needed to serve domestic demand. The remaining more than 10 GW was for export – a clear indication of how foreign demand for German power is rescuing the conventional sector.

An overview of the German power sector last week. The gray area above the red line (representing domestic power demand) is all of the conventional electricity generated solely for export. The sharp dip on May 8 is a glitch in the data, not a drop in production. Source: Agora Energiewende

The week is a bit unusual in terms of the high level of combined wind and solar output. At 1 PM on Sunday, wind and solar alone made up around 62% of German power demand (domestic, excluding exports). Add on power from biomass and hydro, and renewables covered 73% of demand during the midday peak – albeit on a Sunday, when demand is low.

But the same chart shows us a quite small share of renewables at 5 AM on the first day of the week. Hydro is at 2.0 GW, biomass at 3.7 GW – and wind and solar collectively only at around 0.7 GW. Yet, domestic demand was 53.1 GW. Renewable power only covered 12% of demand that hour, when the residual load came in at 46.7 GW.

Germany has a must-run capacity of around 20 GW, meaning that 16 GW (the residual load from domestic demand on Sunday at 1 PM) is simply too little for the German power sector to serve. As the residual load approaches the mid-20s (gigawatts), power firms therefore begin paying customers to take electricity off their hands. Yesterday, power prices went negative for the entire afternoon, as the chart below shows.

Source: EPEX

There are some hard lessons to learn here. I intentionally avoided the headline that “Renewables cover three quarters of German power demand” above, though that statement would have gotten the most clicks. This figure is probably a new record. It is also cherry-picking. Over the first quarter of 2014, renewables made up 27 percent of demand (up from 25 percent for 2013 as a whole), but that share generally fluctuates between 10 percent and 50 percent.

More importantly, negative prices are not good. Granted, they hurt the conventional power firms that have worked to slow down the transition over the past two decades, but we must meter out our cheerleading wisely. The previous week shows us that we continue to need considerable backup capacity on a regular basis. Negative prices make such backup capacity unprofitable.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

On the other hand, regarding the sheer spread between – 70 €/MWh and + 30 €/MWh within a couple of hours, one could say that this looks like an attractive situation for storage providers? The more often wrenewables will cut into the residual load of around 20 GW the more often these providers can benefit from the EVU’s urge to pay for power purchasers. Shouldn’t that promote the business case of pump power for example?

“Shouldn’t that promote the business case of pump power for example?”

Yes but… In the early 80s the US had a surplus of power production. This was due to utility planners overestimating the forecasted load. A lot of this surplus power was Nuclear which has a hard time ramping down… Especially in those days when the operators were having a hard enough time keeping the new plants up and working the bugs out. At night you’d see negative prices so pumped hydro plants would charge up and subsequently sell during the day. The difference between back then and now is that nuclear plants cause the surplus power problem 11 months out of the year whereas solar only causes the problem for 3ish months… This leaves a limited amount of time available for the pumped hydro plants to run and recover their fixed costs. An additional difference between now and 30 years ago is that nowadays we can manage our energy use via smart appliances much more cost effectively.

If direct marketing is implemented you could imagine a situation where “prosumers” contract with pumped hydro facilities. In this situation the prosumers would be charged a storage fee which represents the operating costs of the PHS plant plus some profit – this is likely to be around 5 cents/kWh. This arrangement would likely require the communication of aggregate load from all the prosumers participating in the contract – this would likely require less bandwidth than a tweenage texter.

[…] die gesamte erneuerbare Energie gekauft werden muss, gibt es Zeiten, in denen die Strompreise negativ sind (d. h. man gibt den Leuten noch Geld dazu, damit sie den Strom abnehmen). Weil ein Backup aus […]