Oliver Geden and Severin Fischer of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) recently published a study on how the German Energiewende fits into the European context. Today, Geden sums up the issue for us.

Source: Lupo | pixelio.de

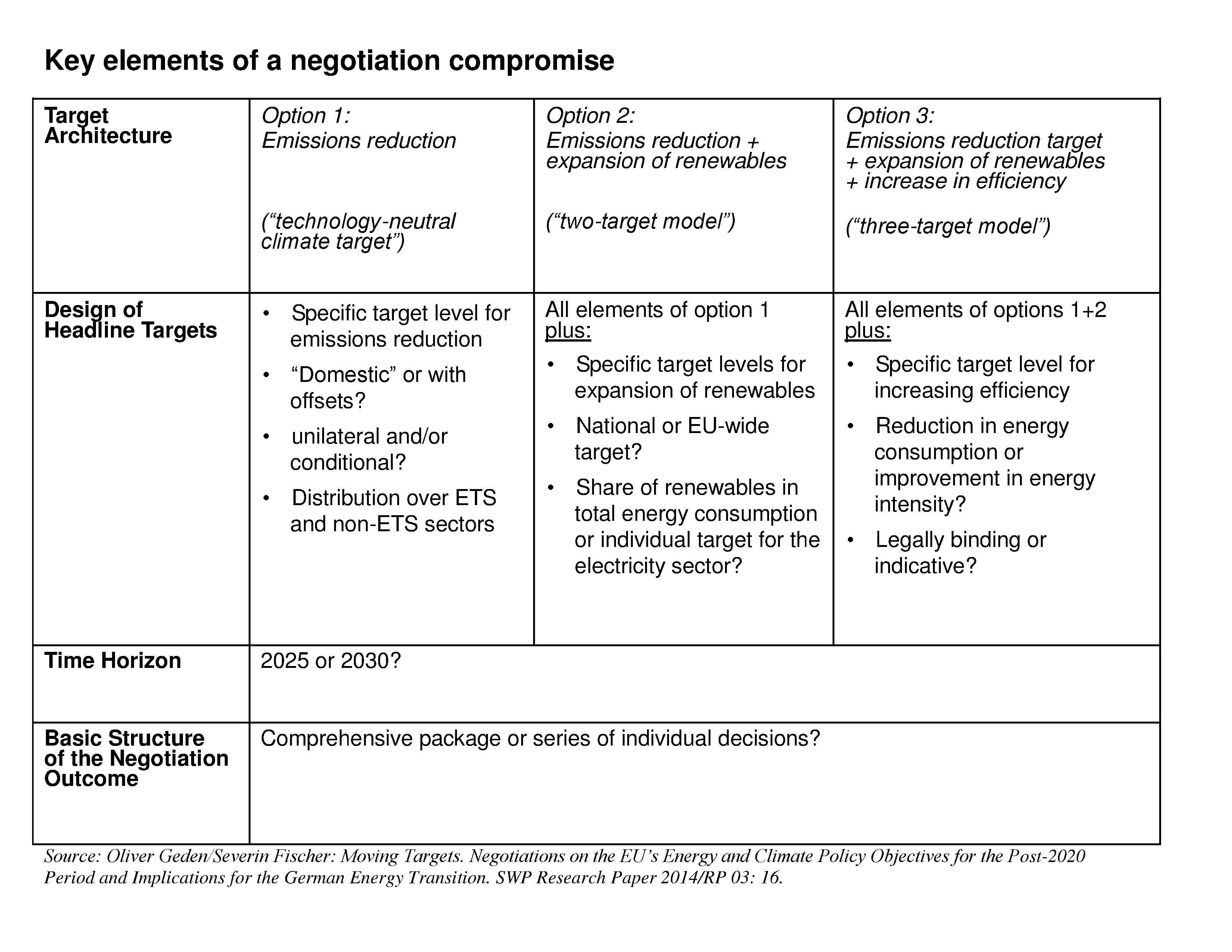

Negotiations between 28 Member States on the EU’s key Energy and Climate Policy Objectives for the post-2020 period are still at an early stage and might only be concluded after the 2015 UN Climate Conference in Paris. Although a basic structure for a compromise (see table below) has emerged even before the Commission’s proposal in January 2014, it is impossible to predict concrete outcomes. Only roughly two-thirds of the Member States have already expressed clear preferences; many Central and Eastern European countries are taking a wait-and-see approach. The European Parliament will only come into play when the 28 heads of state and government have unanimously decided on overarching targets, which will then make it necessary to adapt policy instruments such as emissions trading in the context of legislative procedures.

The course and outcomes of the negotiations over the future of EU energy and climate policy in Brussels will hugely affect Germany’s energy transition (Energiewende) policy. First, the German government will have to develop a negotiation strategy that promises success on the EU level but that can also be presented convincingly to the German public. Second, it will have to deal with the contradictions that are likely to arise between the EU and the German policy framework. The more the EU slows down the pace of transformation, and assuming that German ambitions remain high in the core energy transition areas, the greater these contradictions will be.

The course and outcomes of the negotiations over the future of EU energy and climate policy in Brussels will hugely affect Germany’s energy transition (Energiewende) policy. First, the German government will have to develop a negotiation strategy that promises success on the EU level but that can also be presented convincingly to the German public. Second, it will have to deal with the contradictions that are likely to arise between the EU and the German policy framework. The more the EU slows down the pace of transformation, and assuming that German ambitions remain high in the core energy transition areas, the greater these contradictions will be.

At present, it appears highly likely that the 28 heads of state and government of the EU Member States will set only a moderate emissions reduction target and will not agree on a new renewables target for the entire energy sector. Such a decision by the European Council would create pressure to modify some German Energiewende targets.

Inward turn after Fukushima

A glance at recent history shows that German energy and climate policy has actually undergone an inward turn. This is hardly surprising given the scale of the tasks at hand and the controversy surrounding numerous details of the national energy transition. But the strategy of largely ignoring the European dimension of the Energiewende is not just pragmatic. It is also based on the German self-perception of being a leader in energy and climate policy, whose good example the other Europeans will eventually follow – either by making ambitious decisions on the EU level or by imitating at some later point in time. Past German administrations were able to employ this notion with almost no political risk. They occasionally had to fend off accusations that Germany is too ambitious in its environmental policy, thus endangering the competitiveness of German industry. Yet these debates have not led to widespread questioning of Germany’s leadership role. Furthermore, consensus remains broad in Germany on phasing out nuclear power, reducing emissions, and expanding the use of renewable energy. However, a paradigm shift has begun to occur on the EU level and this will affect Germany’s ability to play a successful leadership role.

Pressure to modify Energiewende targets

At present, it appears plausible that the EU target architecture will be reduced to a single emissions reduction target after 2020 with a low level of ambition – even below the “40 percent domestic” level proposed by the Commission. If this happens, Germany’s key Energiewende targets will be affected in very different ways. While such a decision on a European target would have no negative consequences for the German roadmap to phase out the use of nuclear energy, it might impede Germany’s expanded use of renewable energy. And it is highly likely to have a negative impact on emissions reduction policies.

Even if Europe does not set a new renewable energy target in the same form as the current one, Germany could still set its own national target of achieving 30 percent renewable energy in total energy consumption by 2030. However, if this were perceived by the German public as “going it alone” within Europe, the project of ambitious energy system transformation would meet with substantially increased political opposition. Furthermore, public discussion of the overall costs is likely to flare up again and again in the years to come.

Such discussions might be sparked by European issues, such as the fact that the Benelux countries and France, which have close ties to the German electricity market, profit from the significant decline in electricity wholesale prices across the entire market area thanks to the wind and photovoltaic installations subsidized by German energy consumers. The effort required to maintain network security will probably increase significantly if neighboring countries like Poland and the Czech Republic, which have decided against an energy strategy based on renewables, design their electricity networks in such a way that they are able to block the transit from northern to southern Germany during high-wind periods. The expansion of electricity networks within Germany will probably encounter major acceptance problems in many regions.

In all these cases, the argument could be made that Germany would be better off partially adjusting to a European approach and slowing down the domestic expansion of renewable energies. Against this backdrop, it seems sensible to encourage efforts to further expand the use of renewable energy in the electricity sector, both within Germany and also within the EU. This would not only be in the interest of German industrial policy, but could also make it easier to carry out necessary discussions with neighboring countries about the design of a cross-border electricity market.

What is much more vulnerable to negative European influences is Germany’s emissions reduction policy. In the scenario assumed here, there would still be a basic consensus between Germany and the EU on the role of targets, but the significantly differing levels of ambition would pose a problem. No one can prevent Germany from maintaining its national emissions reduction target of 55 percent by 2030. Yet it is difficult to predict whether Germany would face pressure to adjust its 2030 objectives simply because its own emissions reduction target turns out to be far more ambitious than the EU target.

Additional national measures

Far more critical than the potential problem of increasing doubts about Germany’s future climate policy leadership role is the issue of the deteriorating conditions that such a role would require. An unambitious EU climate target would have a negative impact on the ETS allowance price and would thus exacerbate an already very strong tendency. Since barely half of German greenhouse gas emissions are regulated directly through EU emissions trading, the persistently low allowance price has made it significantly more difficult for Germany to maintain its original targeted emissions reduction path, which was calculated on the basis of much higher CO2 prices. As a consequence, the CO2-intensive energy sources lignite and hard coal profit in particular from price erosion in the ETS and place a growing burden on Germany’s overall emissions balance. Germany will only be able to achieve a direct and short-term increase in allowance prices through initiatives at the EU level. In the chosen post-2020 negotiation scenario, however, such initiatives would have relatively little chance of success.

The German government would be left with only one option to meet its own emissions reduction goals: the use of additional national measures. First, it would have to introduce further regulatory instruments for the energy sector, such as technical emissions performance standards for power plants or a carbon floor price for installations covered by the ETS. Such measures could improve the German emission balance, but this would not lead to a emissions reduction from an overall European perspective since the allowances saved in Germany would be used in other EU countries. Second, Germany would finally be forced to take additional emissions reduction measures in the sectors of transport, agriculture, and buildings, which until now have been largely spared from widely unpopular regulations.

Minimizing EU interference

In light of the complex constellation of interests in EU negotiations, the paradigm shift underway in energy and climate policy, and the continued broad consensus on the transformation of the German energy system, a relatively pragmatic strategy appears to be the most advisable. This approach would center on the attempt to design EU policies that ideally reinforce and support, but at least do not interfere with the German Energiewende in order to prevent EU developments from undermining this flagship project as much as possible. In the EU post-2020 negotiations, the German government would have to concentrate on reaching agreement on a comprehensive package that contains both an ambitious emissions reduction target and a legally binding target for renewable energy.

If the need for further national emissions reduction efforts is to be minimized, the new EU emissions target would have to be formulated in such a way that it directly affects allowance prices in the ETS, for example, by shifting additional efforts from non-ETS sectors to the ETS and strictly limiting credits from international climate protection projects. With regard to the renewable energy target, it will probably be very difficult to reach an agreement in the European Council that covers all energy consumption sectors. From a German point of view, this is not strictly necessary, since the transport and heating sectors are only marginally relevant to the common European energy market and only play a minor role in the German Energiewende discourse. A European energy policy supporting the German energy transition would have to strongly promote the use of renewables in the electricity sector across the EU. Germany will only be able to achieve its national deployment path efficiently through integration into the European electricity network and in conformity with European state aid rules. The German government will therefore have to campaign vigorously for a renewable energy target in the electricity sector.

About the authors

Oliver Geden and Severin Fischer are Research Fellows at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. SWP is the largest foreign policy think tank in Europe, funded primarily by the Federal Chancellery.

This article is based on SWP’s Research Paper “Moving Targets. Negotiations on the EU’s Energy and Climate Policy Objectives for the Post-2020 Period and Implications for the German Energy Transition”. By analyzing the decision-making process mainly from the negotiators’ perspective Geden/Fischer consider the plausible and probable outcomes of negotiations to establish a new EU energy and climate policy framework. The article was originally published at Energy Post and is reprinted here with kind permission.

[…] Full analysis […]

The only problem of our country is that Czech grid is sometimes used for he huge electricity transport from Germany to Germany which cannot be tolled but grid operator has to deal with it. Pay them some decent money for the grid usage and there will be no disharmony and Czech grid can (at least partially) substitute Süd link. It’s over-dimensed (until Temelin 3,4 completion, at least next 15 years) and in a quite good shape.