In a recent article about the German energy transition, a researcher in the US looks at the challenges Germany faces. But Craig Morris thinks the report says more about Americans than about Germany.

The Energiewende is not a result of top-down but bottom-up policies. (Photo by twicepix, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In an article at the Journal of Energy Security, a PhD student in the US investigates the situation in Germany, but she also shows how the Anglo world projects its worldview onto Germany.

First, let’s clear up two sloppy errors – it is the Danish, not the Dutch, who have the highest power prices (not energy bills) in Europe. Germans power bills are roughly the same as those in the US at around a hundred dollars a month. Germans may pay more per unit, but they consume less overall.

Then come several misunderstandings. As readers of this blog know, Germans do not sell “surplus” renewable power to the grid; under feed-in tariffs, they sell all of it. And the “umlage” is the surcharge that covers the cost of these feed-in tariffs; the researcher seems to think the two are separate, but the umlage contains the cost of feed-in tariffs. Furthermore, you do not put a “windmill in your yard” in Germany; you purchase shares of a large community-owned wind turbine nearby. Tellingly, the researcher otherwise focuses on offshore wind power (the domain of big business), whereas the Germans want to own onshore wind themselves.

As readers of this blog also know, the Czech Republic and Poland are not suffering from surges of wind power from Germany, and solar and wind are not “unpredictable”; they are, rather, not dispatchable, meaning that you can’t switch them on.

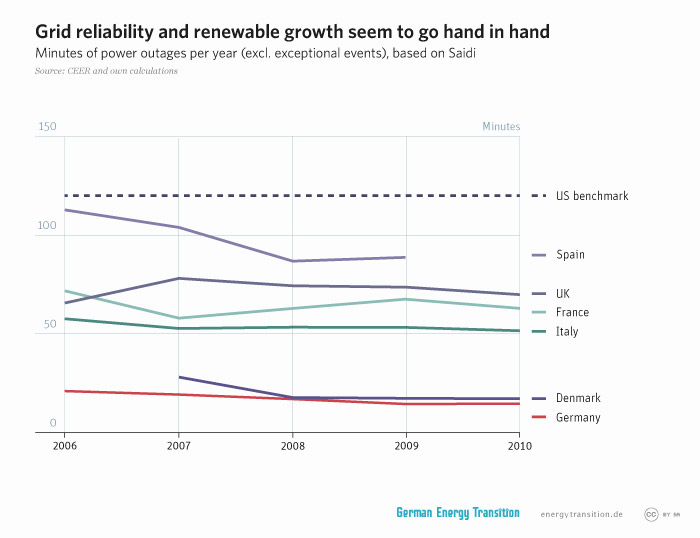

Germany continues to have one of the most reliable grids in Europe (along with Denmark, another frontrunner of renewables).

She claims that Germany has progressed with renewables “more than any other European country, to be sure,” but Germany lags far behind Denmark, and the share of renewable electricity in Spain and Portugal already reaches much higher levels. The example she gives of German progress also reveals her focus on big business: “Deutsche Bahn, Germany’s railway operator” will be 30 percent renewable by 2014. In fact, German electricity was already 22.9 percent renewable in 2012, 5.8 percentage points above the level of 2010. At that rate, all anyone has to do to be 30 percent renewable by 2014 is consume electricity from the grid.

When she states, “The most significant challenge Germany will face will come from its citizens,” she overlooks the history of the Energiewende going back to the 1970s, when German citizens told their corporations: we don’t want your cheap electricity; we want to make our own power, even if it is more expensive.

A few years ago, I wrote in my personal blog about how visitors to Freiburg’s new allegedly car-free neighborhood of Vauban seem to assume that the city does not allow people to have cars, when in fact it was the citizens themselves who petitioned their government to have the district designed with as much car-free space as possible. Clearly, Germany is pursuing an energy transition because the Germans want it.

In my next installment, I’ll investigate the researcher’s most interesting claim – that Germany has built coal plants in reaction to the nuclear phaseout after Fukushima.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.