Delineating between commercial and physical power flows is not a task for the faint-hearted. Fortunately, researchers have done the work for us – and found that power is sold when it is cheap, not to prevent blackouts. As part of a four-part series, Craig Morris discusses a recent study on this matter conducted by the German Institute of Applied Ecology (Oeko-Institut).

Wind Energy in France. (Photo by olympi, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

You might think that European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity would be an obvious place to get such information, but the study’s authors point out that national borders do not always tally with grid control borders, some of which have also shifted over the past few years, further hampering comparisons over the years. Also, the organization’s monthly data represents purely physical power flows (monthly), whereas both physical and commercial data are provided in the hourly data.

And then there is the wonderful footnote on page 46, where the authors point out that the data for power exchanges sometimes exceeded “the physical capacity of the lines.”

Nonetheless, trends can be clearly identified and conclusions drawn. It turns out that the power trading market between Germany, France, and the Benelux countries has had a market coupling mechanism for a few years now. If power unexpectedly flows in a direction not expected based on power sales, the power trader may be left empty-handed, but the transmission grid operator will be paid.

The crucial sentence comes on page 20: “A market coupling mechanism has not yet been introduced for Switzerland and the eastern neighbors of Poland and the Czech Republic.” Here, we see why the complaints mainly come from these countries. The solution also seems obvious: expand power trading to these countries so that more market players get paid their fair fee.

Poland and the Czech Republic are members of the EU, which is currently focusing on strengthening energy trading between member states. The Germans, Poles, and Czechs should therefore be working on opening up their grids and power trading to each other, not on limiting grid connections at the border.

When power trading occurs

A major issue that the study addresses is whether Germany has become more reliant on power imports. One could simply look at the overall trading volume, which reveals that, after a brief dip in 2011, German power exports roared on again in 2012, rising from 6.3 to around 23 terawatt-hours.

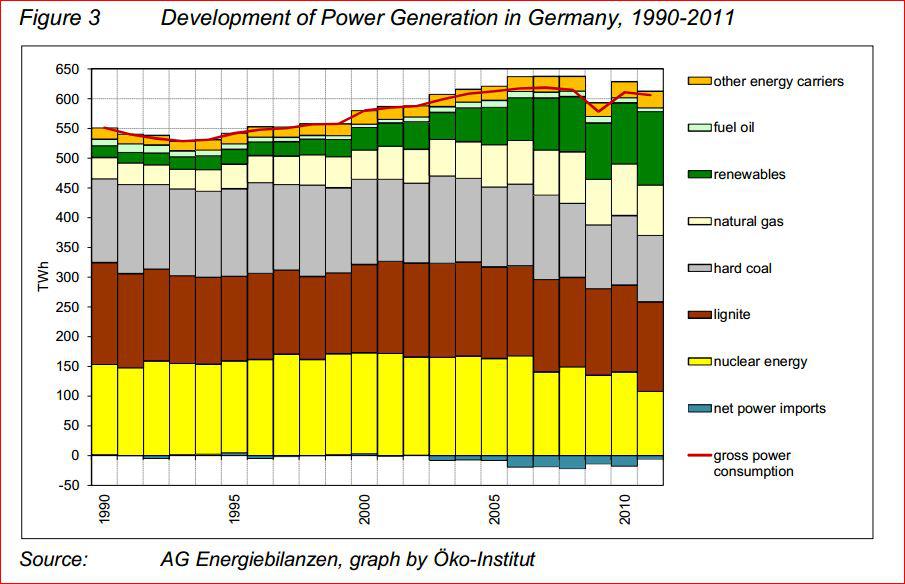

Over the past 20 years, Germany has reduced its consumption of both nuclear and coal power (lignite and hard coal) and has even become a major power exporter over the past decade – right as it began ramping up renewables. And though the chart does not show it, power exports were up again in 2012 to 23 terawatt-hours, roughly the level of 2006-2010.

But the study goes further by investigating when power is traded. If Germany needed to import power for a lack of generating capacity, say, resulting from the nuclear phase-out, we would expect German power imports to increase as the country’s power demand rises.

The opposite is the case; the researchers found that power demand in France seems to dictate power trading more than what Germany needs. Though the researchers do not use the wording, the finding is not surprising because of the inherent inflexibility of nuclear plants.

When power demand is low in France and Germany (the two countries have a similar load profile), France is generally exports power to Germany. The option would be ramping down its nuclear plants, which nuclear reactors do not do well. Likewise, when power demand rises in France and Germany, Germany exports power to France. Whereas Germany still has a dispatchable electricity generation capacity exceeding peak demand, France desperately needs to build new generation capacity to meet its rising power peaks, which crossed the 100-gigawatt threshold last winter – a full 25 percent higher than peak demand in Germany, which has nearly a quarter more inhabitants.

This trend is not limited to absolute peaks and valleys (seasonal) but can be seen across normal business days and when comparing workdays to weekends. For instance, France tends to export power to Germany on the weekend, when demand is low in both countries. Clearly, power trading is the result of prices, not an attempt to prevent power outages resulting from any scarcity of power production – at least not in Germany.

Thus, Germany’s power trading balance depends partly on French electric heating. If we had a very mild winter, France would not import as much power.

In the next installment, we take a closer look at Germany’s eastern neighbors.