As Europe’s energy system shifts from fossil fuels to decentralised renewable energies, one challenge is coming into focus: how can the rising costs of expanding and modernising the electricity grids required for the transport of renewable power be financed fairly and efficiently? And how can tariff design help reduce pressure on the grid by encouraging consumption patterns that make better use of existing infrastructure? Sinéad Thielen examines how different grid and electricity tariff structures can support a fair, flexible and resilient electricity system, and what is needed to protect vulnerable consumers in the process.

Credits: Fré Sonneveld | Unsplash, Public domain.

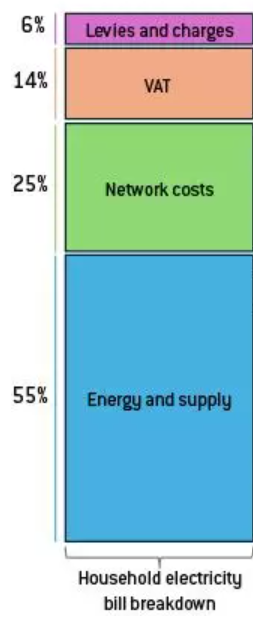

The key challenge of the energy transition is no longer the question of how to produce enough renewable electricity, but increasingly how to efficiently manage its grid integration and distribute it across complex decentralized power systems. Electricity prices consist of three main components: wholesale energy costs, network charges and government-imposed taxes and levies. While wholesale prices are falling thanks to more renewables, these savings are often eaten up by rising network charges, namely the fees consumers pay for using the electricity grid. Today, network charges make up around 25% of household electricity bills, with large variation across EU Member States – a proportion of the electricity price that will foreseeably rise. Maintaining, modernising and expanding Europe’s electricity network is essential to enable the rollout of wind and solar, connect electric vehicles and heat pumps – briefly: meet European climate targets. This will require massive investment, estimated at over €500 billion by 2030 by the European Commission in its Action Plan for Grids. How fairly we allocate these costs will shape public perception and the political viability of the energy transition. Designing fair network charges is therefore not a technical issue alone, but a question of social justice and acceptance. The European Commission has recognized this in its Action Plan for Affordable Energy, where it states that ’network charges should be designed to encourage efficient electricity consumption while fairly distributing costs’. But what design options are there and how can they, in combination with further measures, deliver their part in a European energy transition that is fair and cost-efficient at the same time?

Figure 1: Household electricity bill components (Source: Bruegel)

Design options for network charges to reflect grid use and support equity

The design of network charges consists of at least two elements. There is a fixed charge, paid in euros per point of connection to the grid, and a variable fee based on the amount of electricity consumed.

The latter can manifest in a volumetric tariff, meaning consumers pay their share for using the grid based on the total amount of electricity consumed. This is the most common tariff structure across European grid systems and ensures predictable revenue for grid operators, as well as a financial incentive for consumers to reduce their electricity consumption. The more electricity they import from the grid, the more network charges they have to pay. However, volumetric tariffs do not accurately reflect the actual cost drivers of the grid expansion. These are determined much more by the peak demand than by overall energy consumption. Because what stresses the grid most is not how much electricity is used overall, but the maximum demand that occurs at the same time. A household that uses electricity continuously throughout the day may have a lower impact on the grid than one that charges an electric car, runs appliances and heats the home all at once in the evening. Volumetric tariffs, though, do not incentivise shifting usage away from peak demand hours.

A better alignment with grid cost drivers can be achieved through capacity-based tariffs, where users are charged based on their highest level of usage during a billing period (their peak demand). This demand is physically reflected through the capacity of the cable needed to supply that home: thicker cables allow for higher voltage and can thus handle higher currents, allowing for potentially higher peak consumption at the same time and therefore impacting the capacity tariff. This pricing method reflects more fairly the pressure a consumer can potentially place on the grid during maximum usage hours.

Another option is time-of-use (ToU) tariffs that charge different prices for volumetric consumption at different times of the day, week or year. They can be based on historical data (static) or on adjusted real-time prices (dynamic). This design option is capable of optimally integrating renewables into the grid, but while beneficial for some users, they are not one-size-fits-all: highly dynamic ToU tariffs demand some digital literacy, and they currently tend to pay off only for those households that have the ability to invest in heat pumps, electric vehicles and smart household appliances. Not all citizens, in particular vulnerable households, have the opportunity to engage in these solutions. Consumers without installed smart meters and automated technologies cannot profit as much as wealthier households. Also, households that are unable to adjust their electricity use flexibly are more vulnerable to price fluctuations, especially during sudden spikes. Coping with these unexpected cost increases requires some financial flexibility, which can place a burden on low-income households.

Progressive block tariffs, granting a basic level of electricity consumption, for instance 1,000 kWh per household, at a reduced rate with higher pricing steps applied above this threshold, can help address these inequalities. While they are not specific to network cost allocation, they can be useful in ensuring that basic electricity needs remain affordable. While these models subsidise essential electricity use and alleviate the burden on energy-poor households, they may distort market signals and lead to over- or underconsumption.

In practice, no single tariff model fits all consumer profiles. A combination of volumetric, capacity-based, ToU and progressive elements – adapted to different consumer profiles – can offer a fairer and more efficient approach.

Flexibility as a solution to ease pressure on the grid

The most effective way to avoid rising network costs is to make better use of the infrastructure we already have. That means reducing peak loads and shifting electricity use to times when the grid is less busy or when renewable energy is abundant. While network charges play a role, this part of the discussion extends into the broader design of retail electricity prices. To allow all groups of consumers, including vulnerable households, to benefit from the energy transition and make use of flexible tariffs, several social safeguards and enabling factors need to be put in place. This is important to avoid disadvantaging those who cannot invest in smart appliances or electric vehicles. An option to promote system-friendly consumption for low-income households as well are price corridors for flexible retail electricity tariffs that ensure consumers will not be exposed to peak prices while reaping the benefits of fluctuating renewable prices. Here, it will be important to find the right balance between protecting consumers and allowing for effective price signals. Either way, the wider promotion of smart meters is necessary to give consumers a more granular overview of their consumption patterns and possibly variable electricity prices to benefit from flexible tariffs. This goes hand in hand with schemes that facilitate the purchase of smart devices for poorer households, for example through on-bill financing mechanisms. In such models, part of the initial investment would be paid off through the savings made by lowering the overall energy bill and on revenues gained from providing flexibility. Moreover, it will be important to simplify switching tariff offers by issuing guidance or even binding characteristics for online price comparison tools. The complexity of retail electricity tariff options increases, demanding more transparency in energy contracts, clear pre-contractual communication, and accessible and user-friendly tariff design. This will increase trust in the consumer’s capabilities to reduce their energy bill, as well as in the energy transition as a whole.

Ensuring that the costs of grid expansion are equitably distributed and encouraging system-friendly consumption is now a critical task for policymakers and regulators. Tools for reform are taking shape regarding the European Commission’s preparation of a Grids Package until the end of 2025. It is expected to present a legislative proposal to streamline planning procedures and simplify approvals. Also, a guidance on network tariff methodologies has been published, providing recommendations for national regulators on longer-term infrastructure planning, anticipatory investments, risk-sharing frameworks and approval mechanisms. If done right, the reform of network tariffs can ease pressure on the grid, protect vulnerable consumers and turn the promise of the energy transition into practical progress for all.

The views and opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.