The first of three pieces highlighting the potential of Ukraine’s post-war recovery to pioneer sustainability – especially the energy transition – but warning against complacency. Part 2 focuses on business and finance, and Part 3 highlights the risk of leaving Ukraine out of its own recovery. Josh Matthews reports.

Global leaders of finance, politics and industry can secure and maximize the Ukraine 2.0 vision

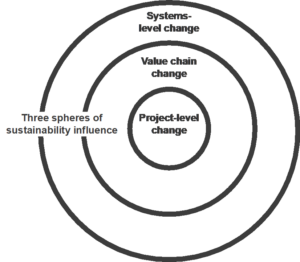

That will take brave decision making. Decisions that look past the barriers in existing global systems of investment, politics and business. Decisions that match the world’s opportunity and responsibility in supporting Ukraine and addressing the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Dozens of environmental, social and economic/governance (ESG) factors must underpin sustainability – crucially achieving a just transition, whether in energy or throughout the SDGs. Ukraine must not only rebuild and house individual projects that meet these goals, but generate full value chain and systems-level change (see Figure below).

The work has started

Policies and planning are coming into place, whether through this summer’s Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC) or the country’s own ‘Ukraine 2.0’ vision. But the world needs to realize that same vision. Leaders of finance, politics and industry with levers to pull should step up. Ukraine’s post-war recovery cannot become a developmental project only. Ukraine can pioneer sustainability across the whole global context. But plans and ambition must be secured now, from all stakeholders.

Razom We Stand, a Ukrainian movement against war and for sustainability, held an event that set the tone for the latest URC held in London. A mix of policymakers, industry leaders and investors came together; Razom published its own take and summary of the discussions here. From these conversations, and subsequent writing by media and numerous other groups, I’m convinced there are enough of the right people working on the technical sides of finance, policy and technology to lay the foundations of a plan to make Ukraine a leader that can trigger systemic change within its borders, as well as across the continent, and be a global example for how sustainability can work across all ESG factors. But for the full ambition to be realized, bold decisions must be made to overcome the barriers of existing systems – not just the challenges of war.

Three spheres of sustainability influence, which can illustrate a new level of ambition for Ukraine’s recovery. Adapted from HFS Research

There already exists a wide ambition, together with economic arguments, for projects, value chains and systems-level change

Razom has published one such report collating the research of academics, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and others, alongside its own call to action. Plans are aligning in both the global sustainability context and the individual needs of investors, industry leaders and policymakers. However, there is some room for improvement, concluded a study published by a research team of Ukrainian nationals and researchers from Oxford University, that the government’s 2022 recovery plan of $750bn could do more across the SDG spectrum.

Razom’s report also referenced research by the Institute for Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. A recovery prioritizing decarbonization and the broader energy transition was modelled to cost just 5% more than rebuilding the old economic, fossil fuel–heavy model. (And naturally that 5% ignores the many social, governance, and wider economic and environmental benefits, which are less quantifiable). Plenty of individual project examples also hold their own on normal investment metrics across the renewable energy spectrum. With renewable energy adoption accelerating in Europe, Razom’s worthy ambition is for Ukraine to be the first 100% renewable nation.

Beyond new energy development

Digital technology and energy efficiency (including addressing methane leaks, which took up a large part of Razom’s Q&A panel) must be in the mix of solutions. Decentralizing power grids and replacing emergency diesel generators further adds to the solutions checklist. Digital and physical infrastructure (required side-by-side for operating ‘smart grids’) come alongside digital and IT services: there’s big potential for the world’s consulting, tech and services firms at all parts of their value chain. (In Part 3, however, we’ll consider the troubling risk of these firms ignoring the collaboration potential with Ukraine’s own experts, NGOs and businesses, both large and small). Ukraine is obviously not starting from scratch on renewables and decarbonized energy: natural potential for solar and wind energy means that renewables have leapt in the overall electricity mix, from 1.8% in 2018 to 8.2% in 2021. But any schemes, like providing guarantees of origin for renewable energy generation purchased, should focus on new capacity building, not simply taking existing capacity from the market without inspiring new development – although it’s right to acknowledge the two do work hand in hand to an extent.

Viewing Ukraine as a development project for global institutions only risks failing its people and losing a chance for global change

Similar concepts can be applied to the benefits on offer from meeting the SDGs globally. We need a pivot from targeting the few trillion dollars available in developmental funding (for the whole world) to the world’s several hundred trillion of total investment potential. Each stakeholder should be clear on their opportunity and responsibility. The case for investing in sustainable development, and projects that hold their own financially on paper, is being further de-risked by joint financial, industrial and political organisations and partnerships. But these opportunities can be further de-risked with the coming together of the right expertise of recognized sources, individuals and firms – and crucially the right data, produced transparently from Ukraine itself, as Razom’s event participants made clear on several occasions.

In Part 2/3, we will consider the need and opportunity for business and finance to make up for the failings and limited power of politics.

About Josh Matthews: Recently the Chief Sustainability Officer and Practice Leader at HFS Research—having built its sustainability research and advisory practice from scratch, while leading the energy, utilities, and supply chain team, and embedding sustainability through HFS’ industry, technology, and business coverage. Speaker at COP26 and other sustainability and industry events. Project and standalone engagements with Fortune 100 CEOs and various global leadership teams. Former Cambridge City Councillor and shadow cabinet member for climate change, environment, and the city centre. Approved parliamentary candidate for the Liberal Democrats. Former Chair and now partnerships lead for the Association of Liberal Democrat Engineers and Scientists. Graduate of Cambridge’s Department of Engineering (MPhil) and Loughborough Chemical Engineering (MEng). Former Process Engineer at TotalEnergies and Visiting Scholar at UC Santa Barbara, publishing work in the Chemical Engineering & Technology journal.