Nature conservation and wind power generation can overlap in oceans – for now.

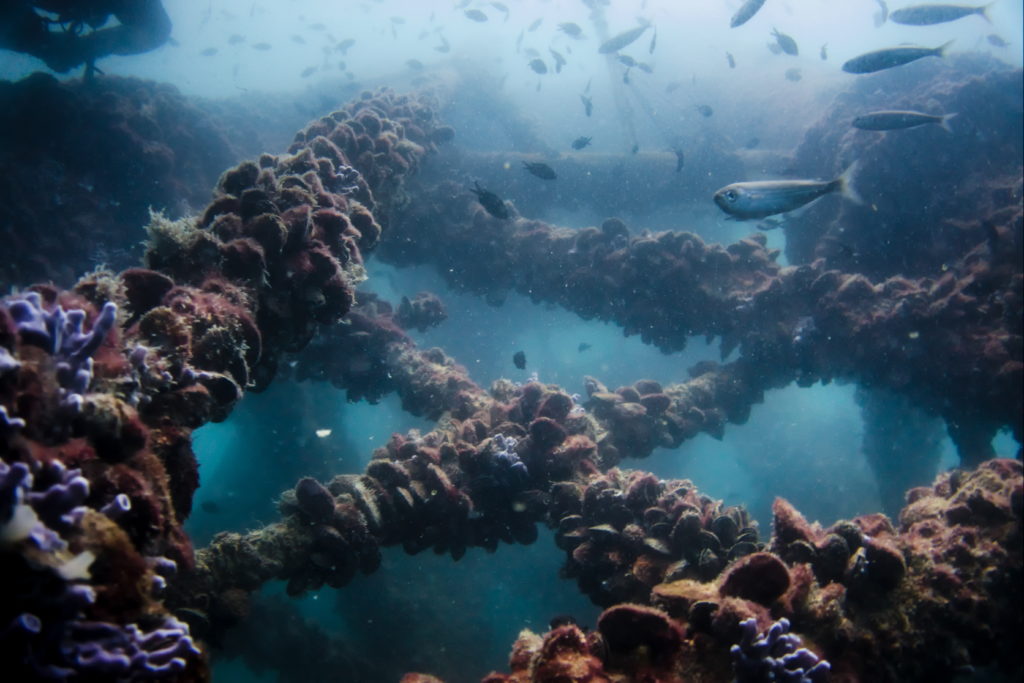

Offshore turbines, once planted, can serve as marine life habitats. (Photo by Enrico Strocchi, CC BY-SA 2.0)

It is uncommon for today’s ever-more gargantuan wind parks to win points for their nature friendliness. Sea-based wind turbines kill birds, confuse dolphins, and crush seafloor aquaculture, charge conservationists. But, according to an new expose in The Anthropocene magazine, marine researchers in the North Sea – from several countries and independently of one another – have come to the same unorthodox conclusions: offshore wind parks protect and even nurture a range of marine life, including threatened species such as North Sea cod and grey seals.

The North Sea is the site of these counterintuitive findings because its shallow waters and gusty coasts have hosted modern turbines for twenty years – longer than anywhere else in the world. During this stretch, northern European wind farms in the waters of half a dozen countries have been off-limits to the fishing industry. This has enabled their underwater environs to develop unviolated by watercraft and the trawling nets that rake the seas and their floors clean.

And the turbines’ foundations on the seabed can also function as artificial reefs upon which flora and crustacea thrive, which then are consumed by fish, porpoise, and seals. Researchers have found that the sea’s renewables energy parks can serve as sprawling marine life sanctuaries – a Kinderstube, or nursery, for underwater species, say Germans – some of them as vast as 80 km2 in size.

The findings are highly relevant, as offshore wind power needs to be built out dramatically in the near future – in Europe and globally – in order to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Until now, this prospect has largely been one of grave concern for conservationists. Planting the giant steel piles into the seafloor destroys part of the seabed and disperses sediment, which disrupt marine ecosystems for kilometres. During the surveying and installation procedures, vessels collide with marine mammals, sea turtles, and fish. And once in place, noise and electromagnetic fields can distract larger fish for the length of the turbine’s productive life. When decommissioned, the masts embedded 30 meters in the sea floor must be removed or replaced (a dirty, expensive procedure currently happening to the North Sea’s oil and gas rigs.)

But an ever-larger volume of multinational research, some of it still ongoing, reveals that the protected marine space could be crucial to rejuvenating fish stocks, shellfish populations, and aquatic marine mammals. Wind parks could actually benefit the natural world – in ways beyond the generation of zero-carbon energy.

Scientists at St. Andrews University in Scotland have tracked grey and harbour seals marked with GPS tags off the Dutch and British coasts. They saw that some of the mammals in the German and the UK wind parks swam in patterns from turbine to turbine, sometimes stopping to forage around the masts. The work coincided with findings that harbour porpoises, a highly endangered species, tended to gravitate to wind parks in Dutch waters, either for purposes of protection or to find prey, such as gobies, herring, and sand eels.

In Germany, researchers have located cod and planted young lobster populations in wind parks. Vanessa Stelzenmüller, a marine biologist from the Germany-based Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute, has tracked schools of North Sea cod off the diminutive archipelago of Heligoland about 80 km north of the port city of Bremerhaven. The North Sea’s cod, a favourite of seafood lovers, has been dramatically overfished which has led to a sharp decline in the population. The sea’s warming waters, due to climate change, is another contributing factor, says Stelzenmüller.

Stelzenmüller has observed the species in a German-owned wind park of 80 turbines that generates enough electricity for about 320,000 homes. Not only were cod living in the park but “we found their condition was better than that of those cod outside the park,” says Stelzenmüller. Recently she and her colleagues ascertained that cod were breeding there, too. “It is remarkable,” she told The Anthropocene, “that even despite the warmer waters in the southern North Sea that the habitat in the wind park suits them better than in the colder northern reaches of the sea.” They enjoy better shelter, protection and forage options.

The European lobster is yet another beneficiary. When marine scientists released 2,500 baby lobster in and around the rock-covered foundations of a North Sea park in the German Bight, they didn’t know what to expect. Three years later, the lobster population had grown, though marginally. They were healthy and larger in size than farmed lobster.

The emergence of wind parks as safe zones for marine life coincides with studies that show that parks, when not located in the path of migratory routes, do not kill larger birds in abundant number (research into smaller birds is inconclusive). Nor are harbour seals unnerved by turbine noise once the masts are embedded in the sea floor.

Yet advocates for the sea’s protection told The Anthropocene that many times more turbines in the North Sea is another story entirely. The cumulative impact of so many turbines bears another quality of systemic risks, they say. The wind parks can benefit nature, they admit, but their expansion must be executed with a light touch and plenty of planning.