Municipalities and civil society have to be involved in the process of defining NECP targets

These days, the cancellation of ceremonies and handshakes between high-level officials is usually explained with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, what does it tell us when Vice President of the European Commission Josep Borrell, in his recent visit to Ukraine, meets with anti-corruption activists before getting together with officials? Are we witnessing the onset of a new kind of morally dignified political hygiene? Oleg Savitsky has the details.

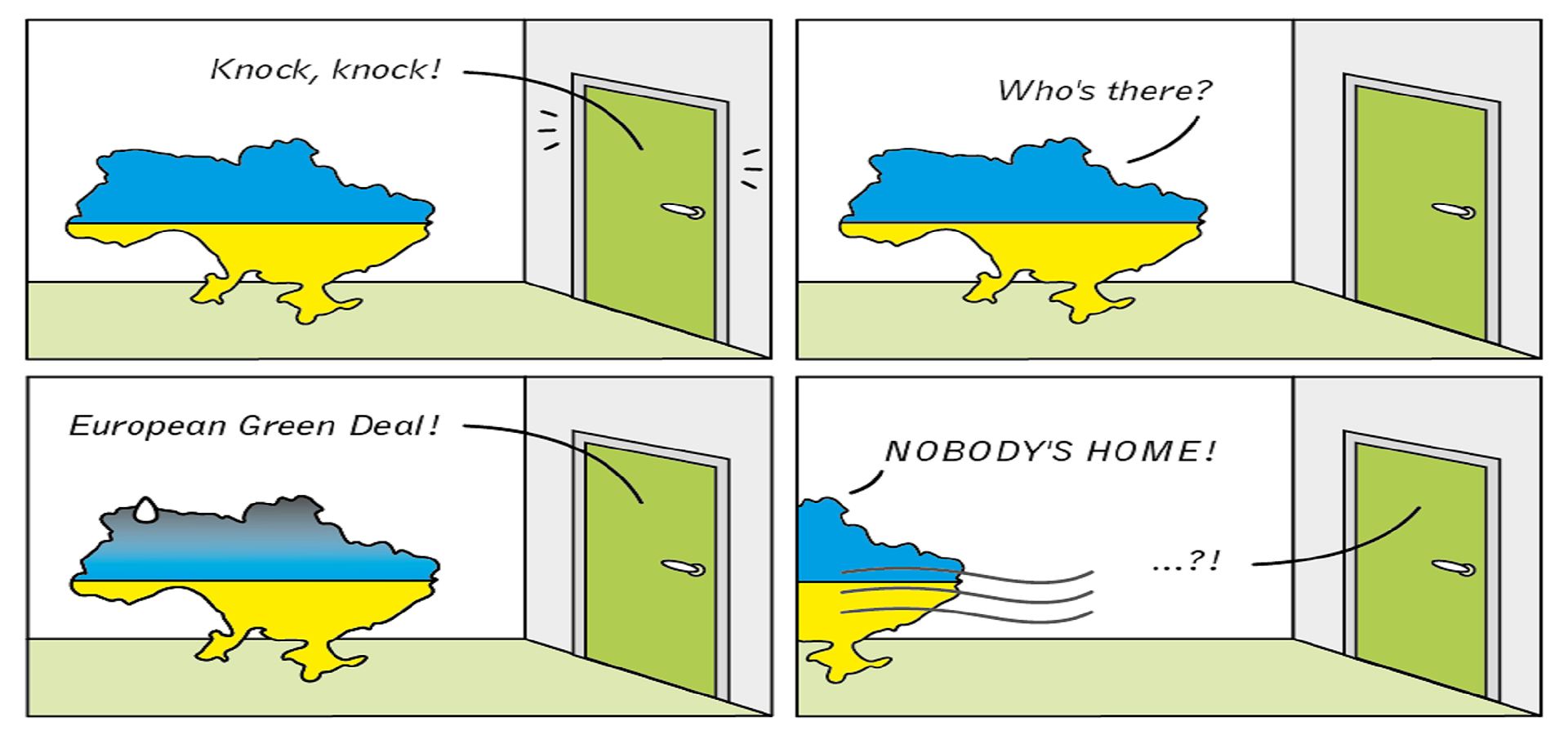

Comics about Ukraine and European Green Deal. (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0, Anastasia Skokova)

The European Green Deal is a flagship project not only within the EU but also for its relations with its neighbours. As such, it is very much dependent on the rule of law and on anti-corruption enforcement. The European Green Deal is a cornerstone on the way towards environmentally-friendly modernisation and the realisation of major investments into green infrastructure and decarbonisation.

Decarbonisation as battlefield – oligarchs vs. change

This year, Ukraine has seen a long series of corruption scandals, personal attacks on activists, attempts to replace management at strategic state-owned enterprises, and a strong backlash against market liberalisation and environmental protection reforms. Since March, after an abrupt reshuffle of the government, Ukraine has gradually given up control over its economy and infrastructure to oligarchs.

Today, critical components of the European Green Deal, such as energy efficiency, renewables, and pollution reduction, which were still in their early stages, are being dismantled by the actions of the new government and the administration of President Volodymyr Zelensky. In 2020, funds intended for environmental protection programmes were diverted to cover non-transparent subsidies for coal mines. Ukraine‛s renewables sector, which attracted record investments in 2019, is now in limbo. An official government memorandum regarding restructuring is not effective, as the rules governing the monopolised electricity market are constantly being changed. The Energy Efficiency Fund, long the poster child of Ukrainian reform policy, will be completely defunded according to the draft 2021 state budget. The Ministry of Energy seeks to postpone environmental compliance or closure of polluting coal plants for another ten years. At the same time, official Kyiv is declaring its commitment to the European Green Deal and to decarbonisation.

In this situation, the EU’s foreign policy faces a critical challenge – will it be willing to take a stand against lobbyists and Ukraine‛s polluting monopolies?

The decarbonisation dimension of the EU-Ukraine relationship

Since 2011, Ukraine is a contracting party to the Energy Community Treaty, the EU’s key policy vehicle for advancing its energy policy beyond its borders. Established in 2006, the Energy Community Treaty initially was meant to extend the EU‛s internal energy market rules and principles to countries in South-Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region. Gradually, the Energy Community acquis was expanded to include legislation on renewables, energy efficiency, pollution control, and climate change and, as a consequence, the Treaty has become a policy vehicle for accelerating the transition to clean energy and the overall decarbonisation of South–Eastern Europe. The Association Agreement, signed in September 2017, reinforced Ukraine‛s alignment with EU climate policy.

The Energy Community established that contracting parties had to incorporate the strategic 2030 targets in their integrated National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs). As is the case with EU member states, members of the Energy Community were obliged to comply with three major targets for 2030: increase the share of renewables in primary energy consumption; deliver energy savings with improved efficiency; and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

On 22 July 2020, the technical assistance project “Low Carbon Ukraine”, which is funded by the German government, submitted a draft NECP to Ukraine‛s Ministry of Energy. According to Presidential Decree №837/2019, the integrated energy and climate plan has to be approved by the government by 30 September 2020. However, this deadline will not be met, as no public consultations have been held. This goes to show that open, inclusive and transparent policymaking faces major challenges in Ukraine. On the administrative level, the government is not building up the absorption capacity required to meet the conditions for non-repayable funding and technical assistance from the European Union. Ukraine’s current government is serving the interests of a few oligarchs. This not only undermines the economic development of the country, it also is a source of instability, endangering the proper maintenance of critical infrastructure (such as gas transit pipelines, gas storage facilities, and nuclear power plants), which, in turn, poses risks for the whole continent. Today, Ukraine remains one of the most carbon-intensive economies in the world.

A telling example: The derailed electricity market reform

Through President Zelensky‛s sudden reshuffle of the cabinet, the former manager of Ukraine’s private, vertically integrated coal and energy conglomerate DTEK, Denys Shmyhal, became prime minister of Ukraine. In 2018–2019, Shmyhal was in charge of the massive 2.3 GW Burshtyn thermal power plant – the cornerstone of DTEK’s monopoly in the western part of Ukraine that is synchronised with the EU‛s electricity grid – and which is also the main source of its electricity export capacity to the EU and is strongly associated with Ukraine‛s “carbon leakage”. This new government immediately changed electricity market regulation so as to favour DTEK and his owner, one of Ukraine‛s major oligarchs, Rinat Akhmetov. As a consequence, and after a strong performance in the previous year, Ukraine‛s renewables sector saw a sharp downturn because feed-in-tariffs were retroactively reduced. Also, political control over the National Energy and Utilities Regulatory Commission (NEURC) has increased.

Ukraine‛s government is now trying to strike a deal with the European Commission, in order to bypass EU environmental regulations on air pollution, extend the lifetime of depreciated coal power plants, and strengthen DTEK’s domestic electricity market monopoly, while, at the same time, maintaining access to European markets for the dirty electricity generated by the Burstyn thermal power plant. The Burstyn plant‛s efficiency and emission levels per kWh are approx. 50% worse than those of Polish or German coal-powered plants, and therefore the implementation of any kind of Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism would result in the shutdown and decommissioning of this plant.

NECP to be based on bottom-up decarbonisation roadmap

Ukrainian civil society organisations emphasise that what is needed is long-term and systematic planning in the energy sector, including nuclear safety issues, as well as restructuring and continued public spending on energy efficiency, air pollution control, and other environmental programmes. The key measures towards decarbonising Ukraine are a well-organised coal phase-out plus the dismantling of the electricity market monopoly, and this has to go along with a long-term, localised approach to ensure a just transition in the coal–mining regions.

It is possible and necessary to reduce Ukraine‛s greenhouse gas emissions, transition to decentralised renewables, and to introduce new energy-efficient technologies. The implementation of these measures could be the key to an equitable economic recovery after the COVID-19 crisis.

Ukraine‛s civil society demands that the proper financing of environmental protection and energy efficiency measures shall be reinstated in the 2021 budget. Experts and civil society have developed a roadmap towards feasible decarbonisation. The 2030 Climate Goals Roadmap for Ukraine includes quantitative targets for five sectors: energy, buildings, transport, waste, plus one subsector, which includes agriculture, forestry and land use. These goals are based on an analysis of the legal framework, international examples and best practice, as well as the experience of the public and leading experts within these sectors.

A number of Ukrainian cities have already committed to clean energy and overall decarbonisation, and, accordingly, they have developed their own local climate and energy plans. Zhytomyr was the first city to commit to a 100% renewable energy target by 2050, and it has already demonstrated what is possible in the short term. Zhytomyr has switched completely to LED-based street lighting, constructed a municipal solar power station, and commissioned an administrative services centre, which is the first municipal building in Ukraine with zero emissions. Local authorities in Lviv, Mykolaiv, Kamianets-Podilskyi, Chortkiv, Trostyanets, and Baranivka have also set themselves the target of switching to 100% renewables by 2050, and they already are working on the implementation.

Transparent and effective climate and energy governance in Ukraine requires inclusive discussions and active public participation, especially involving municipalities, as they will do most of the groundwork – and civil society organisations with long-term vision and expertise. Open public debate and the participation of local government representatives is an effective antidote to centralised political corruption and rule of oligarchs. It is therefore in the EU’s best interest to ensure that an inclusive and transparent national dialogue on the 2030 targets will take place in Ukraine, a dialogue that will enable the adoption of an adequate and viable NECP.

Ukraine do their work in green policy very good!

Ukrainians bought more electric cars than all neighboring countries to Ukraine.

Ukraine has a very low level of CO2 emissions!

Despite this, emissions continue to decline.

Ukraine has reduced fossil fuel consumption by more than 50 percent in 30 years.

Also, about 70 percent of electricity production in Ukraine is clean energy. (hydro, nuclear, and green).

In energy policy, Ukraine is better than many EU countries.