Ineos who? That was more or less my response too when I first heard of Ineos. And yet in 2019 Ineos was once again among the global top 5 chemical companies (in terms of sales, which totalled €27 billion). Ineos is also the top European producer of ethylene, the basic feedstock in today’s petrochemical industry and an essential component in the production of plastic. Andy Gheorghiu reports

Fracking4plastics on tour.

Fracking4plastics on tour.

Since 2016 Ineos plays – by its own account – a key pioneering role in the European chemical industry. The company is doing this by focusing heavily on fracked gas as a feedstock for its plastic production.

At a time when there is an urgent need to drastically reduce both the use of fossil fuels and the production and consumption of plastic, Ineos is deliberately basing its investment policy upon business models that belong to the past. This has made the company a key target of the anti-fracking and anti-plastic movements in recent years.

A brief history

Ineos was founded in Antwerp in 1998 by Jim Ratcliffe (the main shareholder with around 60% of the shares). Ineos grew rapidly by buying up a wide range of chemical companies, including Innovene, which Ineos acquired from BP in 2005. This made Ratcliffe the owner of the huge Grangemouth chemical site in Scotland. The deal cost Ratcliffe – by now one of the richest people in Britain and a multi-billionaire – around €5.72 billion, which he secured with loans and junk bonds totalling some €5.49 billion. The level of debt grew over the years – partly as a result of further company purchases. The financial crash of 2008 gave Ratcliffe’s empire its first thorough jolt. In 2009 Ineos’s debt had increased to around €6.7 billion and Ratcliffe was forced to consider closing sites such as Grangemouth.

The trans-Atlantic #Fracking4Plastics connection

But instead of closing Grangemouth, Ratcliffe decided to put a proposal for massive new investment before his creditors – who include the usual suspects behind the financing of the climate-damaging and environmentally harmful oil/gas/chemicals scene, such as Barclays, Merril Lynch and Morgan Stanley. With this ploy, Ratcliffe secured coverage of the company’s huge debts for a prolonged period of time.

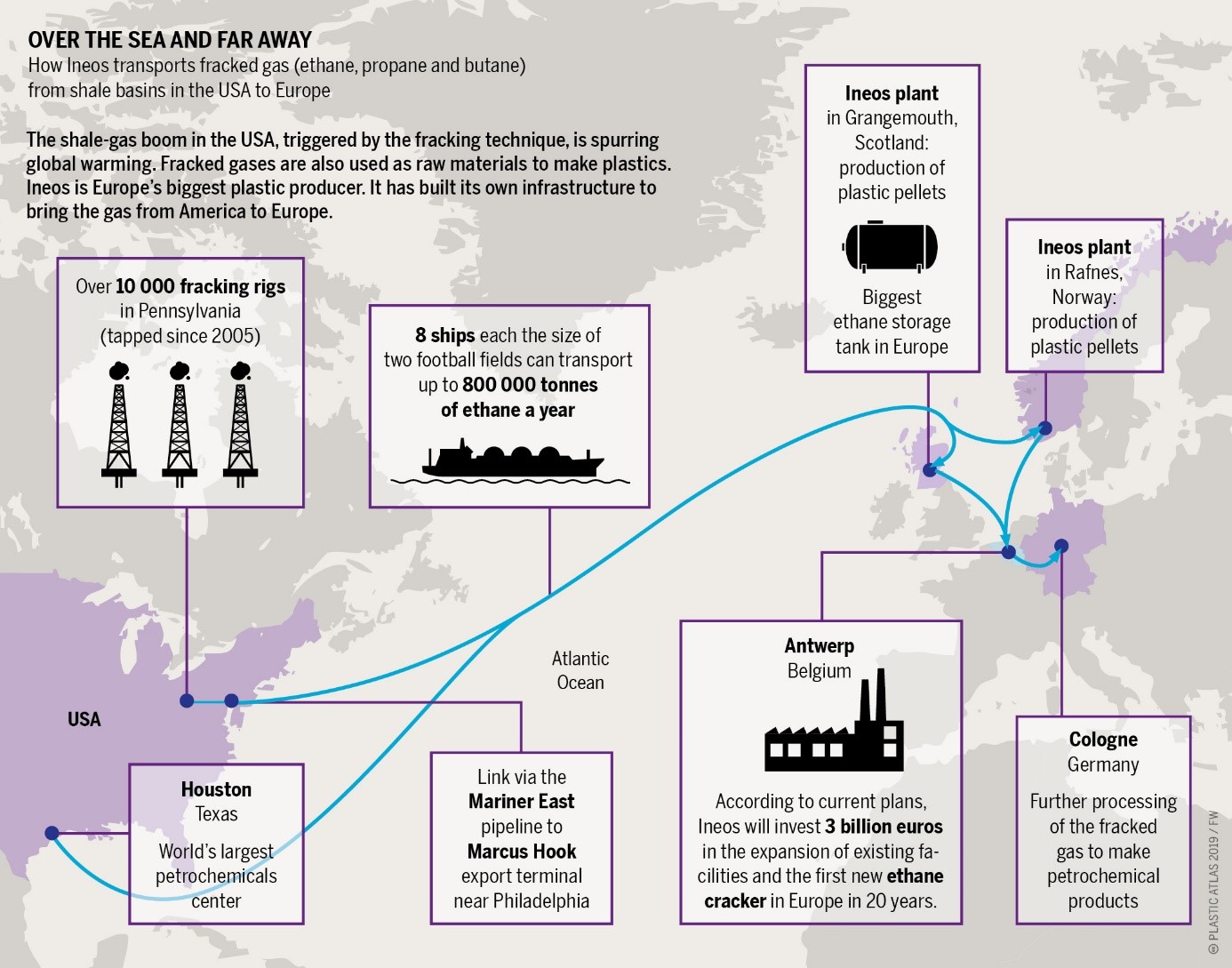

Somewhere along the way Ratcliffe hatched the plan of focusing specifically on fracked gas as a feedstock for plastic production and building up a trans-Atlantic supply chain. At that time, the gas extracted by the fracking industry – especially in Pennsylvania – contained a large proportion of “wet gas” (i.e. ethane, propane or butane) in addition to the “dry gas” (i.e. methane). For a long time this wet gas was simply a by-product for frackers in the US. The rapid expansion of fracking in a very short time (more than 10,000 wells in around 10 years in rural Pennsylvania) was not only accompanied by huge adverse impacts on the climate, the environment and human health but also produced a glut of ethane, propane and butane. Initially, there there was no sizeable market for these by-products. The result was that prices fell, making ethane in particular attractive as a feedstock for plastic production.

Methane, ethane, propane, butane…?

Methane (“dry gas”) can be used by the petrochemical industry to generate electricity for its very energy-intensive processes or to manufacture fertilisers. Ethane, propane and butane (“wet gases”), on the other hand, are valuable as feedstocks for a wide range of chemical products, such as plastic. Many shale deposits, such as the Marcellus and Uttica shale formations in the USA, contain a particularly high proportion of wet gas.

One of the lorry convoys that are delivering water, sand and chemicals to a fracking site in rural Pennsylvania. Photo taken in Pennsylvania on 6 March 2020, Andy Gheorghiu. All rights reserved

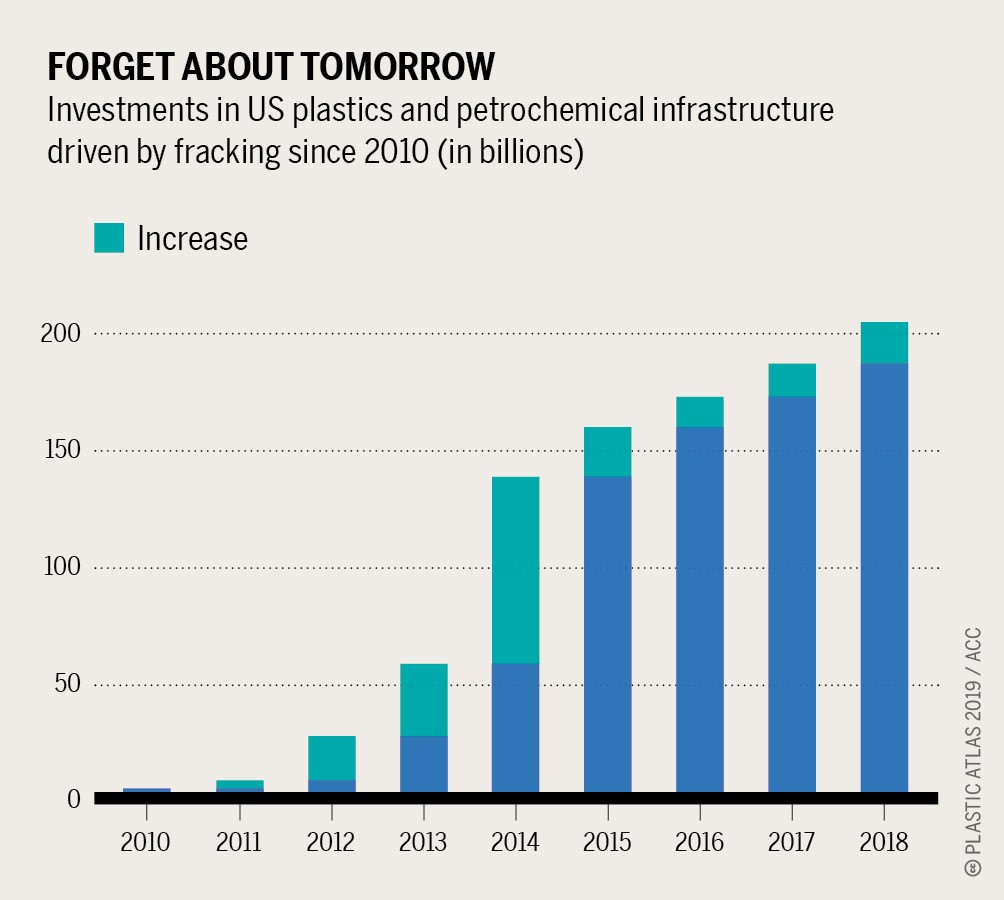

This led to an “unholy polluter alliance” between the fracking and chemical industries (with players such as Shell, ExxonMobil and Total, who make profits in both business areas). The American Chemistry Council estimates that the US chemical industry – on the basis of access to fracked gas – has spent or plans to spend around €170 billion on 343 projects since 2010.

Source of diagram: Plastic Atlas (link: https://www.boell.de/en/plasticatlas)

Source of diagram: Plastic Atlas (link: https://www.boell.de/en/plasticatlas)

Jim Ratcliffe no doubt saw this wave coming and put everything on it in a bid to save his collapsing debt-ridden empire. Ineos commissioned the construction of its own shipping fleet to deliver fracked gas from the USA to the company’s plastic factories in Scotland (Grangemouth) and Norway (Rafnes). Each of these Dragon-class ships (of which there are eight in total) can transport up to 27,500 m³ of gas (either as liquified dry gas or as ethane). Ineos also entered into supply contracts with the US companies Range Resources and Sunoco – a subsidiary of Energy Transfer, the company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) project, which was to be pushed forward by force and against the will of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe.

The Ineos-Sunoco deal centres on realisation of the Mariner East pipeline project to secure the supply of fracked gas from Pennsylvania. In what seems to have become almost a typical feature of the #Fracking4Plastics business model, the €2.5 billion Mariner East pipeline project has from the outset been beset by a series of significant incidents that have led to judicially imposed shutdowns and criminal investigations. The partner of Ineos, Sunoco, has on several occasions been ordered to pay fines in connection with the construction of the project. One of the biggest penalties amounted to around €10.5 million. In August 2020 Sunoco again paid around €300,000 for multiple environmental violations.

Source of diagram: Plastic Atlas (link: https://www.boell.de/en/plasticatlas)

Source of diagram: Plastic Atlas (link: https://www.boell.de/en/plasticatlas)

Furthermore, because the ethane that Mariner East is due to transport is highly explosive and the pipeline is being built close to settlements, sports grounds and kindergartens, people along the pipeline are protesting against the project.

But Jim Ratcliffe and Ineos are not interested in any of this. When the Mariner East 1 pipeline was twice shut down in the spring of 2018 because of possible “catastrophic results impacting the public”, Ineos petitioned officials to support the project on the grounds that Mariner East is important for the export of ethane as a feedstock for Ineos’s European petrochemical facilities. Indeed, the company itself states that by switching to fracked gas as a feedstock it shifted overnight from loss to profit; the losses for the affected communities, the environment and the climate were of course not considered.

Poor environmental, accident and climate record

It is perhaps also not surprising that Ineos cares little about the adverse impacts of the Mariner East project and the risks associated with it. After all, Ratcliffe’s company has accumulated an impressive list of accidents and infringements of environmental regulations and labour laws, for which Ineos has repeatedly been fined.

Over the last ten years there have been – at regular intervals – fires, gas and oil leaks and uncontrolled escapes of toxic substances at almost all Ineos facilities in Europe. At its sites in Cologne there are repeated explosions that have to be carried out to relieve pressure; the most recent was in August 2020. In September 2017, 14 workers were hospitalised with blast trauma. Ever since the major fire of 2008, nearby residents have lived in constant fear of the next disaster.

Jim Ratcliffe is aware of these frequent accidents, which in some cases could lead to a major catastrophe. At an interview with the London Business School in 2015 he spoke of the “symbiotic relationship between the local community and the chemical plant”, which is important because “occasionally things go wrong” and you therefore need the “sympathy” of local people. Yet instead of safety being increased, the opposite is sometimes happening. In early 2020 there was a spontaneous strike at one of the facilities in Antwerp that lasted almost two months. It began when Ineos dismissed a trade-union member and long-serving employee who had pointed out the lack of safety at the plant and the resulting risks.

Although Jim Ratcliffe likes to paint a different picture, his facilities – especially those that are fed by fracked gas – make a significant contribution to global warming and emit a whole range of pollutants into the atmosphere. Ineos has repeatedly – most recently in June 2019 – been declared the worst air polluter in Scotland.

Fracking plans in England and Scotland rejected – next stop Texas?

Ratcliffe may have sensed at an early stage that, for a variety of reasons, the supply of fracked gas from Pennsylvania was not totally secure in the long term. The Ineos boss therefore decided to turn slowly but surely into an oil and gas producer, thus ensuring control of the necessary feedstocks throughout their life cycle.

As well as buying the Forties pipeline system from BP, Ineos also acquired the complete oil and gas business of the Danish company DONG, thus becoming one the top 10 extraction companies in the North Sea.

At the same time, Jim Ratcliffe secured the majority of shale gas licences in Scotland and England and attempted to use a court injunction to nip all anti-fracking protests in the bud. It did not take long for large-scale resistance to Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s feudal gestures to emerge.

The civil resistance finally forced politicians to act. Both Scotland and England have now imposed moratoria on fracking. The Scottish moratorium, which still needs to be fully enshrined in law, aims to permanently ban fracking on account of its harmful impact on the climate. In England, by contrast, the fracking moratorium was introduced on account of concerns about earth tremors and announced shortly before the 2019 parliamentary elections to stop it becoming an issue in the election campaign. However, the ban can be repealed quite easily at any time. And Ineos remains the owner of the shale gas licences.

Nevertheless, the years of opposition have resulted in significant losses for Ineos. At the end of 2018, Ineos Upstream Ltd – a subsidiary that acts as holder of the licences – had debts totalling around €144 million (compared with some €43 million in 2017). The operational loss as a result of the ban on fracking in Scotland and England amounted in 2018 to around €94 million (as against €7 million in 2017).

The fracking route is now blocked in the United Kingdom. Since Ineos is still eager to maintain access to low-cost fracked gas, the company is now attempting to pursue its fracking plans in Texas. It has bought drilling licences from the Houston oil company Crawford Hughes and filed for fracking permits in the Austin Chalk formation. The Austin Chalk also contains wet gas, such as ethane. It remains to be seen how long #Fracking4Plastics in Texas goes well for Ineos.

Expansion plans for Antwerp and the Cologne connection

Another piece of the jigsaw in Jim Ratcliffe’s climate-damaging and environment-degrading #Fracking4Plastics business model is the announced €3 billion investment in new plastic production facilities in Antwerp. Ineos is not only declaring quite openly that the new facilities will use fracked gas; it also wants the construction projects to be seen as kicking off investment for the revival of the European petrochemical industry as a whole.

Directly linked to this investment is the construction of a new gas tanker that will ship fracked gas from Antwerp to the facilities in Cologne. Jim Ratcliffe is thus demonstrating once again that he is deliberately banking on the failure of the anti-plastic and anti-fracking movements.

He would do better to focus on halting pollution by the plastic pellets that are one of his basic products and that cause vast problems around the facilities in both Grangemouth and Antwerp. Thousands of plastic pellets turn up on beaches and even in protected Natura 2000 sites. So far, though, he seems to be lacking the motivation to address this. This is hardly surprising: politicians and government agencies are ignoring the criticism from environmental associations and continue to treat these structural crimes as petty offences.

Plastic pellet pollution in the Port of Antwerp (Natura 2000 site “Scheldt and Durme estuary from the Dutch border to Ghent”, site code: BE2300006), photo taken on 5 July 2019 by Andy Gheorghiu. All rights reserved

Plastic pellet pollution in the Port of Antwerp (Natura 2000 site “Scheldt and Durme estuary from the Dutch border to Ghent”, site code: BE2300006), photo taken on 5 July 2019 by Andy Gheorghiu. All rights reserved

Opposition

Although not everyone is familiar with the name Ineos, the impacts of Jim Ratcliffe’s business model and his unscrupulous behaviour and arrogance with regard to the needs of our time are provoking resistance everywhere Ineos has a presence.

And that’s a good thing!

At the end of the day it will not be politicians or government agencies or buyers of plastic goods that will put an end to Jim Ratcliffe and his outdated ideas of “dirty business come what may”.

No, the chemistry giant from the world of plastic will eventually be brought down by persistent and passionate people and activists from small and large communities on both sides of the Atlantic who face up to Ineos on the front line, despite all setbacks. Campaigners in the United Kingdom have already proved that it can be done.

And the giant may already be faltering: the company is again seeking a state bailout and in its 2019 annual report it states that it is “significantly indebted”, with loans and credits of around €6.9 billion. In the spring of 2020 the rating agencies FitchRatings, Moody’s and S&P Global classed Ineos’ outlook as negative. Well, cheers to that!

A well written and well informed article. Living within the glow of INEOS Grangemouth I recognise and share the concerns raised here. INEOS does not look for or care about a social licence with its neighbouring communities and has one driver- profits at all cost.

Very interesting info about Ineos and fracking in particular. May I translate your article in Dutch and put it on our website http://www.grootoudersvoorhetklimaat.be ?

yes, that would be great!