While ostensibly trying to craft policy that both transforms Germany’s energy sector to 65% renewables by 2035 and protects the security of Germany’s 20,000 coal workers, the Grand Coalition Government’s halting energy policies have just cost the jobs of over 30,000 workers through the wind sector. Facing the worst domestic slowdown in 20 years, manufacturers spent much of 2019 hemorrhaging jobs, going bankrupt or heading into reconstruction. As 2020 begins, L. Michael Buchsbaum brings us up to date.

Germany’s wind energy sector will suffer greatly from the recently adopted regulations in the coming years (Public Domain)

Going off the rails

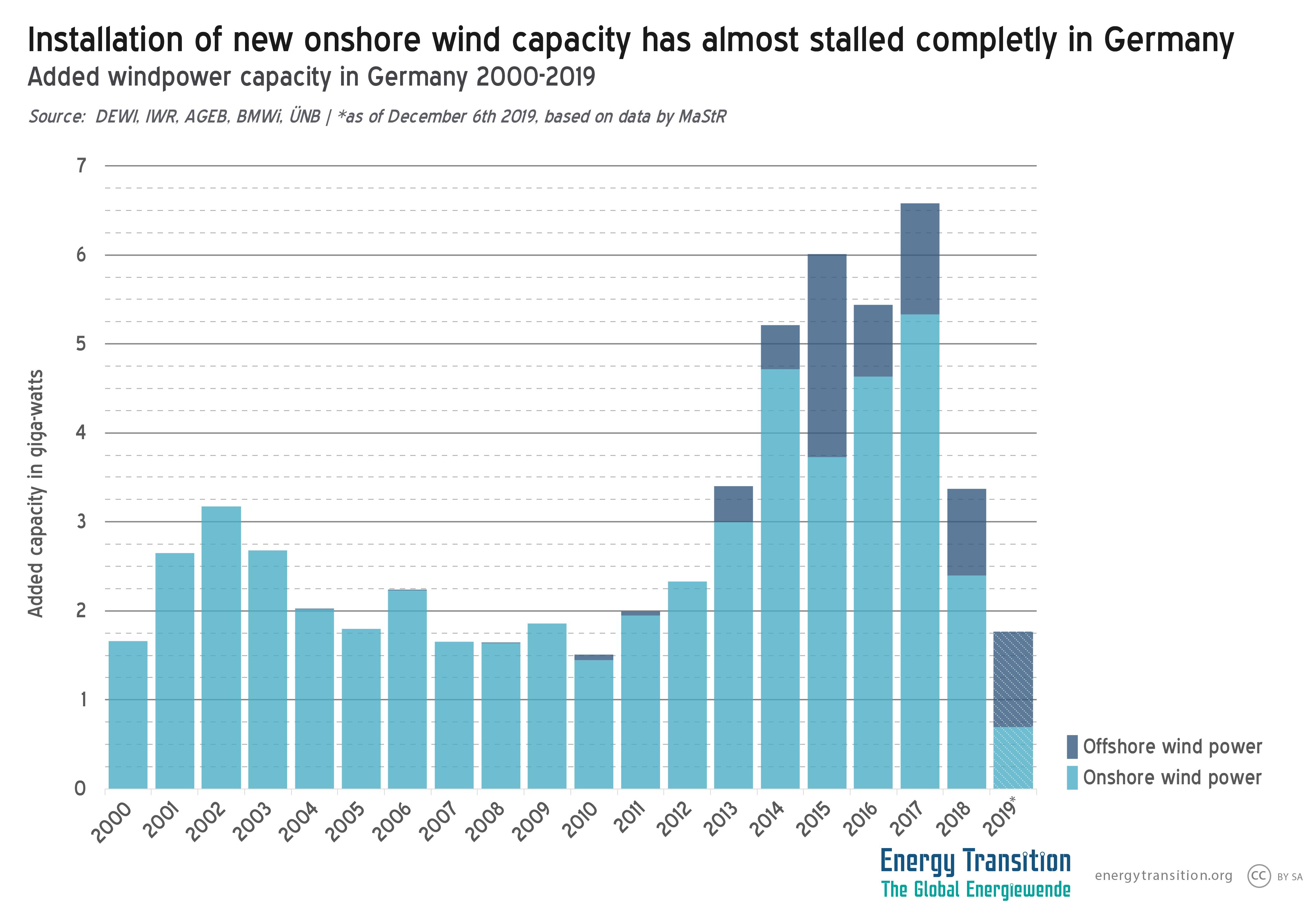

Since 2017 there were many signs that Germany’s wind energy sector was heading for trouble. Once the world’s wind leader, the industry essentially matured here while erecting over 20,000 wind turbines with a capacity of around 48,000 MW throughout Germany since 2000. As more were added to the grid, insiders started warning that mangled new auction schemes were starting to hold back future markets. But the situation continued to deteriorate as the rates of permits slumped and bureaucratic hurdles were erected ever higher. Combined with pushbacks from nature conservation groups (some used as fronts for anti-wind interests), and the rise of the anti-wind right-wing AfD party, Germany’s wind train came to a halt.

According to the UBA, Germany’s federal environment agency, by the end of November 2019, only around 160 new wind turbines had been built nationwide as year-on-year expansion of onshore turbine capacity dropped by over 80 percent. Including repowering, i.e. the replacement of old systems with more powerful wind turbines, the installed capacity only increased by 618 megawatts (MW) – this corresponds to only about a quarter of the capacity increase planned for the year. By comparison: Since 2000, Germany built around 1,100 turbines on average per year with a capacity of over 2,500 MW per year.

1000 deadly cuts

Desperate to change course, last autumn industry representatives met with the powerful Economic Affairs and Energy Minister, Peter Altmaier (CDU) for a so-called “wind summit.” After what they perceived to be a series of constructive meetings, the industry hoped the Grand Coalition’s long promised Climate Package would bring some relief. Finally released at the end of September, embedded within was instead a poison pill nearly certain to bring the whole industry to its knees: a thousand meter residential distance rule, mandating no new builds going forward within that perimeter.

Ostensibly meant to both appease wind opponents while smoothing the way for new expansion, Hermann Albers, president of the German Wind Energy Association (BWE), fears instead the rule will prove a “fatal” blow as it drastically shrinks the land area available for new turbine construction by some 20-50% according to calculations by the UBA.

Moreover, the minimum distance not only concerns the construction of new installations but also the continued operation of existing ones that will start to lose their guaranteed feed-in remuneration after 2020. According to the BWE, 4 GW of capacity will drop out of the renewables support scheme after next year, meaning that a net reduction of installed capacity is possible if nothing is done. So just as wind energy exceeds lignite in Germany for the first time, official government policy may actually reduce it going forward.

All of this flies in the face of the stated goals of the new Climate Package, which calls for renewables to power at least 65% of the country’s electrical needs by 2035. Even though wind energy now constitutes a quarter of production, to meet its share of the projected energy quota, the German Renewables Association (BEE) estimates that an installation of 4.7 gigawatts (GW) of new onshore wind is required. Though renewables are producing some 40-43% (depending on final figures and definitions), a recent study by the Agora Energiewende think-tank states that about three-quarters of the additional capacity needed for 2030 alone will have to come from wind.

Failed policies lead to bankruptcies and huge job losses

With over half of Europe’s 300,000 wind energy jobs located throughout Germany, conservative estimates suggest some 30,000 to 40,000 wind-industry jobs were lost throughout 2019. If the situation continues, up to 27 percent of the roughly 64,000 jobs directly linked to onshore wind power could be lost by 2030, according to a recent study published by VDMA Power Systems.

Throughout the first ten months of 2019, Enercon, one of the largest German wind turbine manufacturers, saw installations sink to their lowest level in 30 years. Workers installed only 65 new windmills with a combined total capacity of 210 MW throughout the country (compared to 711 turbines with over 2 GW of capacity throughout 2017). With the future darkening, Enercon cut over 3,000 jobs or 17% of its workforce—while blaming the politicians for being unable to correct their course.

“The current energy and climate policy endangers not only know-how that has been built up over years and jobs in our industry, but also climate protection and the Energiewende [energy transition] as a whole,” said Enercon managing director Hans-Dieter Kettwig. “Worse, after the presentation of the climate protection package of the federal government, it becomes clear that problems for us will become even bigger.”

In early 2019, embattled German wind equipment manufacturer Senvion filed for insolvency. Rival manufacturers Vestas and Siemens Gamesa have also announced major job cuts.

With so many jobs being lost, many are questioning why Berlin continues to plan to pump billions of euros into regions that will lose jobs in the wake of the country’s planned exit from coal and lignite, while no aid is being offered to the wind industry.

Suicidal tendencies?

“We have been here before,” said Norbert Allnoch, head of IWR, an international renewable-energy economic forum. The present condition of the German wind industry is a stark reminder of the collapse of the German solar market in 2012-14, “which also shrank by 90% due to political regulation, with the loss of tens of thousands of jobs,” he continued.

In an interview with Capital, Senvion CEO Yves Rannou worried as well that Germany’s wind industry might face the same grim fate as the country’s solar panel manufacturers if nothing changes (CLEW provides a great historical review here). “I cannot comprehend why the government would accept that a technology of the future and key industrial competencies that Germany built up for years are being destroyed.” Though policymakers alone can’t be blamed for all of Senvion’s troubles, government policies ultimately “pushed us over the fence,” he lamented.

Though new rules were expected before last year’s end with amendments to Germany’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG), German environment minister Svenja Schulze said in late December that too many questions remained unresolved to reach an agreement before 2020. Chancellor Merkel said the new law was likely to be decided on by her cabinet in March.