It happened quickly and quietly. Within only two minutes, Prague City Assembly members managed to discuss and approve a local obligation to reduce CO2 emissions by 40 % by 2030 during a meeting last September. Of the 58 assembly members present, 40 voted in favor and nobody was against. Petra Kolínská takes a look

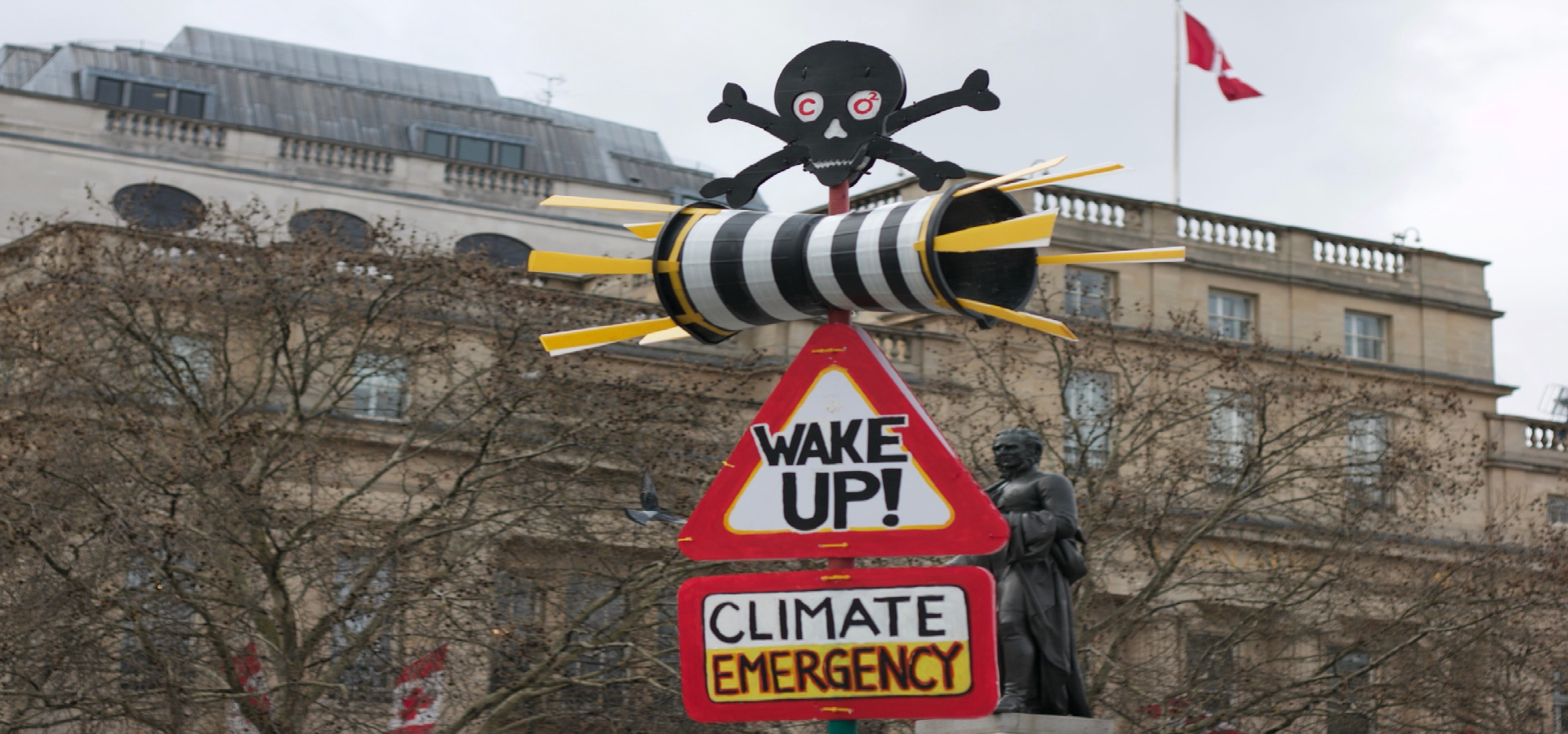

Municipal Departments of Prague announced a state of climate emergency in June 2019 (Public Domain)

Half a year later, a very similar plan became the source of passionate debate. Many assembly members did not support a new proposal that was just slightly more ambitious. What changed during those six months?

EU funds as motivation

In September 2018, Prague joined the Covenant of Mayors. As part of that voluntary platform, the city pledged to fulfill EU targets in the areas of climate and energy policy.

An indisputable advantage of this platform is that it pays attention to checking the fulfillment of this pledge, to monitoring its progress, and also to sharing both good practices and those that are less successful. An answer to the question of why Prague joined can be found in the background materials to the Covenant: full-fledged members of the platform have better access to EU funds. Some of the financial resources, especially for the area of energy, are accessible to Covenant signatories only.

Students as cheerleaders

The calm that accompanied the approval of the climate obligations last September sharply contrasts with the debates on the issue being held in the capital’s assembly this year. This change of atmosphere coincides with the abrupt political disruption after the local elections in October 2018. The Pirates made it into the City Council leadership, as did an entirely new group, “Prague together” (Praha sobě), which is a grassroots citizen movement with a partly green agenda. The main trigger for the debate, however, was the increasing pressure from the public. None of the parties running had set CO2 emissions reduction a priority.

The current interest on this issue was kick-started by high school students. Along with activists from Extinction Rebellion and local sympathizers, they have begun to point out the inaction of the public administration on this issue, at both local and state level.

Through the combination of an appeal to politicians and the student strikes, the engaged public has achieved an unexpectedly fast turnaround on this issue. The mainstream media, which had helplessly avoided this subject in recent years, began to offer more or less informed commentary and news reporting about it. The Government and legislators are so far keeping quiet about the young people’s challenge, while local politicians, with a few exceptions, are hesitating to respond to it.

However, the capital is an exception. The Municipal Departments of Prague 6 and Prague 7 announced a state of climate emergency in June and pledged themselves to many new measures. Among the most ambitious innovations are environmentally responsible public tenders. Various supplying companies (e.g. service providers or construction works), for instance, will have to take into account the life cycle of their products, use environmentally safe materials, or minimize their energy consumption.

At the capital level, the subject of preventing climate change has been on the assembly’s program twice.

Since the increasingly active civil society wasn’t satisfied with the tame content of the first overview, assembly members brought the topic back on the agenda again in June. This time the proposal was more ambitious and focused on limiting CO2 emissions. The capital, in accordance with UN recommendations, has established the climate pledge of “reducing CO2 emissions (…) by at least 45 % by 2030 (compared to 2010 levels) and to achieve zero CO2 emissions by 2050 at the latest.” Some of the new measures the city is meant to immediately start implementing relate to “a change to the rules for buying electricity for the needs of the city and all of its subsidiary organizations such as to provoke the building of new production capacities using renewable energy sources with a view to covering at least half of the city’s current and future needs from such sources by 2030”. The resolution may have been supported just by assembly members from the parties in the local coalition government, but none of the 65 assembly members voted against it.

Dispute continues

The approved resolution and the content of the debate about it have clearly demonstrated that a genuinely demanding time lies ahead. Even among those who supported the climate pledge, the hope is still dormant that all can be done without making any basic structural changes.

The litmus test of the city’s willingness to go beyond its comfort zone may be the planned construction of a new runway for the Václav Havel Airport. The co-chair of the Prague Greens, Vít Masare, has pointed out that this private investment will be a fundamental new source of CO2 emissions. He has drawn the attention of assembly members to the fact that Prague has an opportunity to delete this construction from its own land-use plan and to push the Government to remove it from the national one.

The willingness of the city assembly can also be tested in terms of easier measures. Among those would certainly be adapting the Prague Building Code so that it will be possible to construct apartment buildings and entire residential zones without costly underground garages or parking structures. So-called “car-free zones” with a minimum number of parking places correspond to the right of residents not to own a car and not to pay the considerable costs associated with the building and operation of parking spaces when buying or renting apartments.

Mark September 2020 in your calendar – that will be the moment the capital city’s assembly members will approve the Action Plan. The preparations are being taken care of by a newly established expert commission under the leadership of the former Environment Minister and former Green Party chair, Martin Bursík. It is precisely his name that should guarantee the public that the Action Plan will be comprised of measures which will be not just environmentally vigorous, but also economically feasible.