The complex merger deal will transform Europe’s worst polluter, RWE, into one of its largest renewable energy generators allowing it unprecedented behind-the-meter influence as partner E.ON dominates German grid distribution and consumer access. This poses a threat for competition and could upend Europe’s energy transition.

RWE, historically Europe’s most polluting company, will grow even larger following the merger. (Photo courtesy Buchsbaum Media)

What’s the deal?

When Germany began liberalizing its energy markets twenty years ago, power plants, grids, and sales were divided into distinct portions under four large conglomerates, RWE, E.ON, EnBW and Vattenfall. But if this new proposed merger is approved, E.ON and RWE, whose headquarters are located just a few blocks from each other in Essen, will roll out a new model of horizontal segmentation, giving each partner a controlling market position out of the gate.

As envisioned, RWE will acquire all of E.ON’s and daughter company, Innogy’s global renewable energy assets, ironically transforming the new RWE into the third largest renewables generator in Europe with a nearly 9 GW portfolio and several GW more in the pipeline. Innogy was created only in 2016 by a financially humbled RWE to house its “risky” renewable assets. Now, as part of the deal, the parent is reclaiming those profitable new toys back, along with its crosstown rivals. When the financial dust settles, RWE is set to become the second largest offshore wind operator worldwide.

The new E.ON in turn will concentrate on grid operation and end-use services, taking over all of RWE’s existing power lines and grid holdings, customers, and EV chargers. E.ON will also assume RWE’s 76.8 percent stake in Innogy, taking over that unit’s regulated energy networks, retail businesses and customer operations assets as well.

Moreover, the new RWE will also take a 16.67 percent stake in the re-vamped E.ON, including minority shares of Innogy’s gas storage business and a chunk of their holdings in Austrian energy supplier Kelag. It will also fold E.ON and Innogy’s combined solar expertise – including their subsidiary installation and operation units, into the engorged firm. In a remarkable about-turn, the new RWE expects renewables to become its primary profit generators. To borrow from the film, Good Will Hunting, “How do you like them pineapples now, Dr. Grossman?

Following the merger, the new E.ON will essentially operate most of Germany’s (and a major slice of Europe’s) grid – delivering electricity to tens of millions of customers while RWE, historically Europe’s most polluting company, will grow even larger, expanding to produce close to one-third of the continent’s electricity from a mixture of nuclear, fossil and renewable sources.

“Renewable energies and conventional power generation are two sides of the same coin. And we will have them both under one roof,” said a gleeful RWE CEO Dr. Rolf Martin Schmitz while discussing the merger.

No longer just filthy RWE

Following completion of the proposed deal, roughly 60 percent of RWE’s overall global generation portfolio, including holdings in Germany, eastern and western Europe as well as North America, will be produced from zero (renewables, hydro and nuclear) or low carbon dioxide (fossil gas) emitters. Additionally, the company plans to invest about €1.5bn per year in renewables—roughly 2-3GW of new solar and wind annually.

Monopoly fears

Since March, however, the €43bn deal has been held up by a European Commission (EC) competition investigation that is provisionally scheduled for completion on 20 September, according to the EC website. The probe was launched because of concerns “that the remaining competition would be insufficient to constrain the market powers” of the expanded entities, a view shared by many smaller firms including green energy providers Naturstrom and Lichtblick.

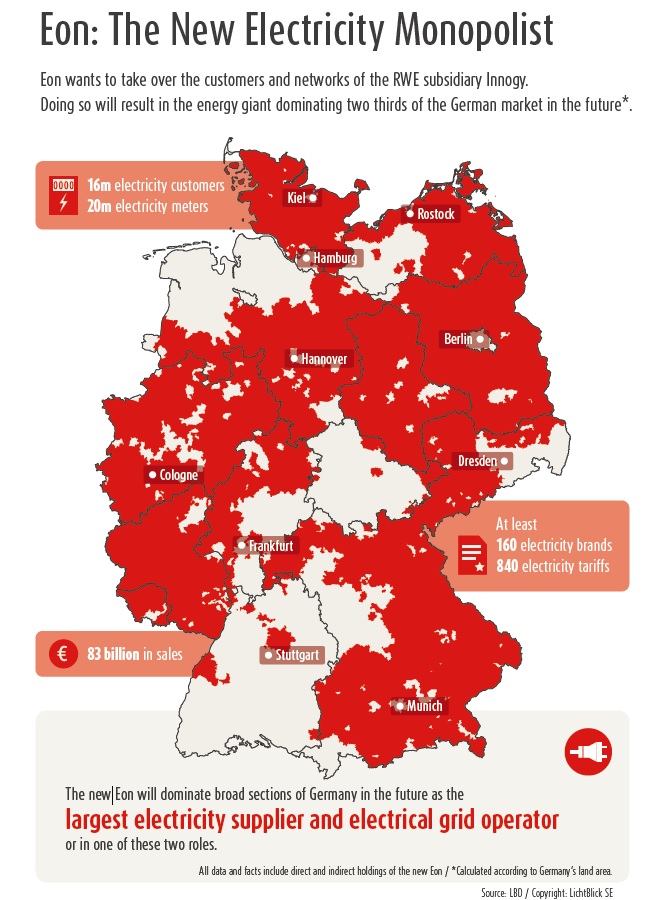

Following the merger, Eon will become the largest electricity supplier and electrical grid operator in Germany. (Graphic courtesy LichtBlick)

However, if the deal goes through, the new E.ON will immediately be in a dominant delivery position across Germany and much of Europe especially in emerging markets like Electric Vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, smart meters, and smart-home solutions, enabling E.ON to generate, track and control vast amounts of energy and consumer-use data as the whole power sector increasingly digitizes.

With so much power in their hands, independent producers worry that the new companies’ respective market shares and combined weight will squash competition, stifle innovation and hold back the on-going energy transition.

“E.ON needs to divest from its participation in municipal and regional utilities in Germany,” said Tim Meyer, a board member at Naturstrom. “Only that way can you avoid E.ON simply crushing smaller competitors in the power retail and distribution grid operating businesses.”

Lichtblick, the largest provider of green energy and green gas in Germany, worries that if the new E.ON becomes the colossus they fear, with a majority of consumers across two-thirds of Germany, the entire liberalization concept will be turned on its head.

“This will be a game changer,” said Ralph Kampwirth, head of corporate communications in an interview with EnergyTransition.org. “Given all their shares in local energy providers, E.ON will have over 16 million customers under the new firm, while owning more than half the grid in Germany,” he continued.

Just as concerning is that the two companies will gain even more influence over Europe’s incomprehensibly complex grid. The new E.ON will essentially define “easy and fair grid access” through much of Germany and Europe going forward—all but guaranteeing a massive source of future revenue and profits. “We fear their market control could be used to undermine competition as consumers are soaked with overcharged grid fees,” worried Kampwirth.

Concerned green-energy consumers will likely be even more confused after the deal given that the new E.ON is poised to control some 250 different retail energy-supply brands, many of which regularly mask their true ownership. Already “many consumers who do change their energy providers from E.ON to another firm mistakenly choose another E.ON product because they are not aware of which ones are actually owned by the company,” continued Kampwirth.

RWE demands billions to shutdown climate killing coal

Another vital question still on the table is the future of coal across the continent—with old RWE being Germany’s biggest miner and burner. Earlier this year, RWE’s Schmitz accepted that “New coal-fired power stations no longer have a place in our future-oriented strategy,” and this summer the company announced the planned early 2020 closure of its 1.56 GW Aberthaw B power plant in Wales after nearly 50 years of operation as part of the UK’s coal phase-out.

But back in Essen, RWE is demanding EUR 1.2 to 1.5 billion in government compensation for each GW of shut down capacity. As Berlin develops a new climate and energy plan, one wonders how much sway ministers will have over the new firms’ combined power.