In the upcoming days Japan will hosts its first ever G20 Summit. As the main contributers to global warming, the G20 states agreed 2009 on a phase out plan of fossil fuel subsidies. Ten years later the failure of the G20 to act on global warming is evident: around $63.9 billion was spent by G20 countries this year to develop coal industries in the global south. Dr. Rainer Quitzow reveals the facts.

G20 states finance coal-fired power plants in developing countries (Public Domain)

The G20 nations, which are set to meet on 27 and 28 June in Osaka, Japan, account for about 80 percent of global CO2 emissions. This gives them a key role in the implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement. But they not only determine whether to pursue a climate-friendly energy policy in their own countries; they also play a crucial role in influencing policies in numerous partner countries. The G20 includes the most important donor countries for bilateral energy-related development assistance: China, Germany, France, Japan, and the USA. It is disastrous that these countries continue to invest in coal-fired power plants through development aid and export financing.

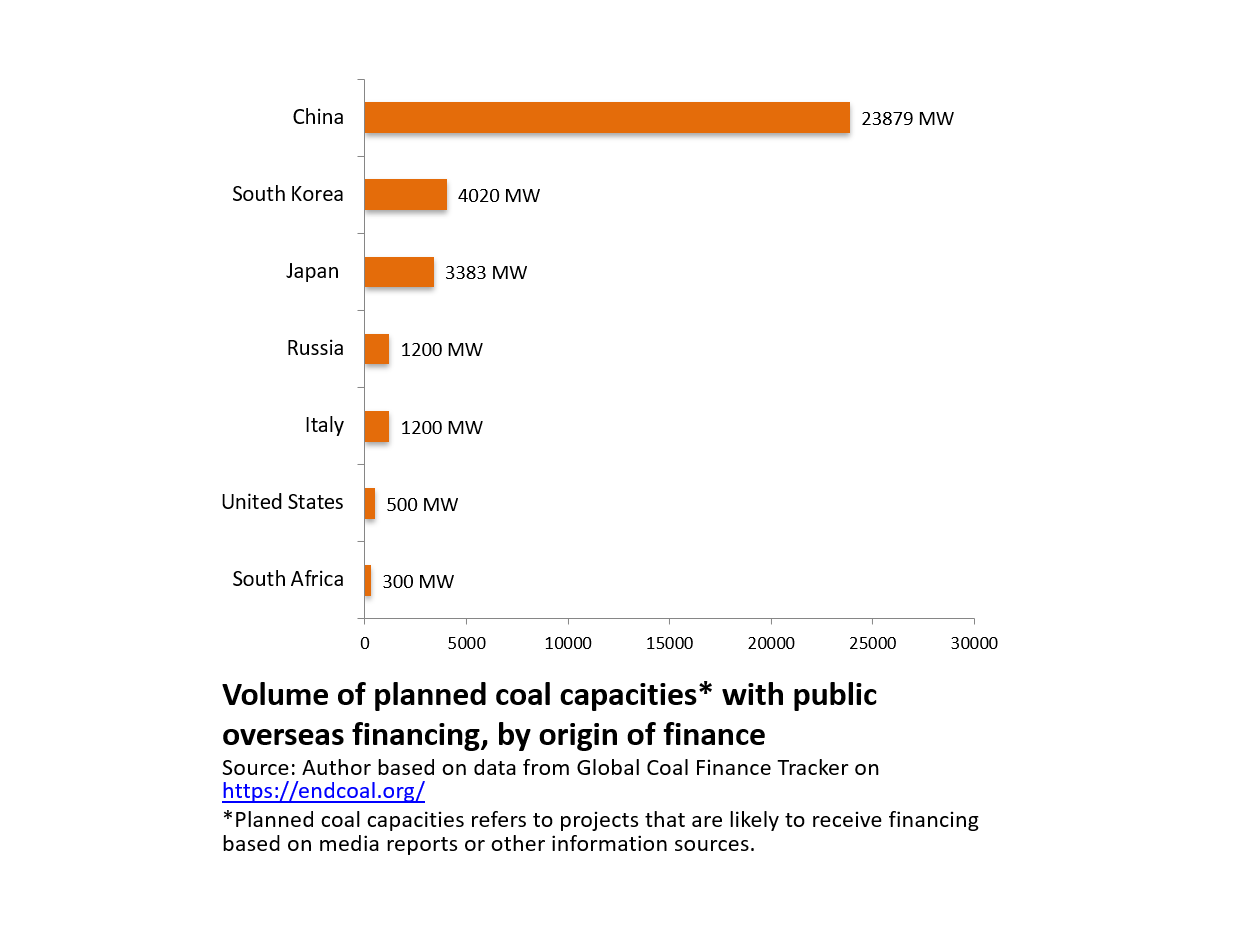

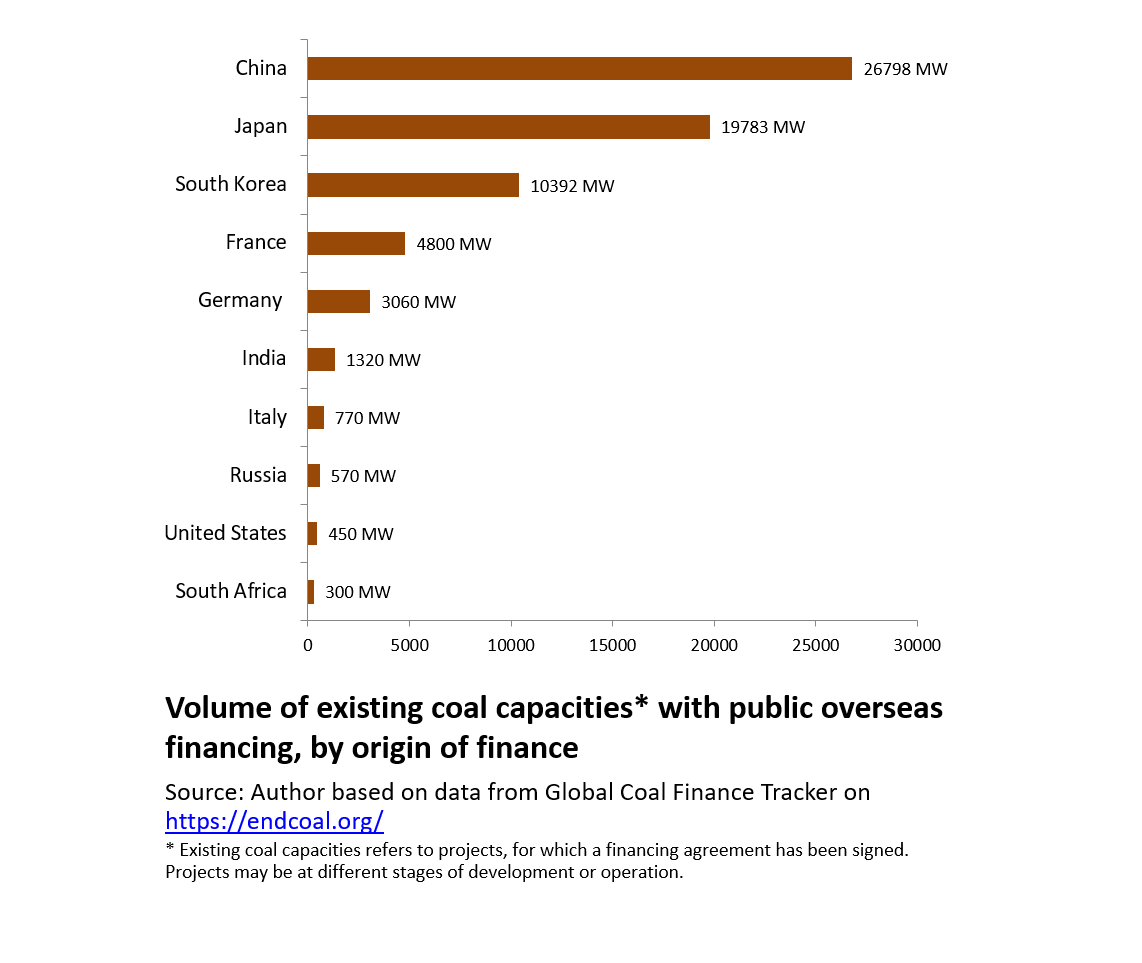

Since 2013, the G20 countries have financed coal-fired power plants with a combined capacity of over 50 GW. Among the funders is the German development bank, KfW, which has helped to build coal-fired power plants in India and Greece. However, the Chinese government has been by far the most lavish in funding coal power abroad. While China’s central government has started to back away from coal-fired power at home, it actively supports investments by the Chinese coal industry abroad. Since 2013, it has funded coal-fired power plants with a combined capacity of over 26 GW via state-owned lenders such as the China Development Bank. A further 23 GW of coal-fired capacity is planned in 18 countries in Asia, Africa, Europe and South America. This represents more than twice the planned investment of the other G20 countries combined.

Japan, this year’s host of the G20 summit, also plans to continue funding new coal-fired power plants, for example in Vietnam and Indonesia. The country is thus under suspicion of violating the OECD guidelines on export financing in the energy sector, agreed in 2015. These guidelines stipulate that coal-fired power plants with a capacity above 500 MW must, at a minimum, be equipped with highly efficient, ultra-supercritical boiler technology, which can reduce CO2 emissions by around 10–20 percent. However, certain Japanese-funded projects do not appear to have included this technology. The G20 members Italy, Russia, South Africa and the USA also continue to fund coal-fired power plants through public export financing, albeit to a much lesser extent. For example, the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) is poised to fund a new coal-fired power plant in Kosovo. The World Bank, which has only financed coal-fired power plants in exceptional cases since 2013, turned the project down in 2018 due to its high costs.

Japan, this year’s host of the G20 summit, also plans to continue funding new coal-fired power plants, for example in Vietnam and Indonesia. The country is thus under suspicion of violating the OECD guidelines on export financing in the energy sector, agreed in 2015. These guidelines stipulate that coal-fired power plants with a capacity above 500 MW must, at a minimum, be equipped with highly efficient, ultra-supercritical boiler technology, which can reduce CO2 emissions by around 10–20 percent. However, certain Japanese-funded projects do not appear to have included this technology. The G20 members Italy, Russia, South Africa and the USA also continue to fund coal-fired power plants through public export financing, albeit to a much lesser extent. For example, the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) is poised to fund a new coal-fired power plant in Kosovo. The World Bank, which has only financed coal-fired power plants in exceptional cases since 2013, turned the project down in 2018 due to its high costs.

Support for new coal-fired power plants not only has long-term consequences in terms of climate change, it also entails significant economic risks for the recipient countries. Even as leading insurance companies such as Allianz and AXA announce their withdrawal from the coal sector in order to protect their customers, the economies of poor countries such as Bangladesh, Zimbabwe and Montenegro are being burdened with debts for the construction of new coal-fired power plants. With expected operational lifespans of 40 years and longer, these plants are clearly incompatible with international climate protection goals. The risk that they will become so-called stranded assets is therefore high. Moreover, now that the costs of solar and wind power have fallen sharply, attractive alternatives exist for expanding the supply of renewables-based electricity.

The Japanese government has placed two key global environmental challenges on the agenda of the G20 summit in Osaka: climate change and marine plastic polluion. These issues have been discussed in a ministerial meeting on energy and the global environment in the run-up to the summit. Similar to past summits, the G20 states have declared their support for a transformation of the energy system and the phase-out of fossil fuel subsies. Like other subsidies, state-supported export financing also reduces the cost of fossil-based electricity generation.

The Japanese government has placed two key global environmental challenges on the agenda of the G20 summit in Osaka: climate change and marine plastic polluion. These issues have been discussed in a ministerial meeting on energy and the global environment in the run-up to the summit. Similar to past summits, the G20 states have declared their support for a transformation of the energy system and the phase-out of fossil fuel subsies. Like other subsidies, state-supported export financing also reduces the cost of fossil-based electricity generation.

It is cynical for G20 countries, with China the leading culprit, to support the a transition to clean energy, while continuing to promote large-scale coal power abroad through cheap loans. The G20 should acknowledge that public financing of new coal-fired power plants distorts the market and undermines the pricing of climate risks by private financiers. It should follow the example of the OECD and adopt the directive on export financing in the energy sector. However, this can only be a first step. Both the OECD and the G20 should agree to completely withdraw from coal financing in the near future. That would also involve the G20 calling on all multilateral development banks to ensure that no new investments are made in coal-fired power plants.

Dr. Rainer Quitzow is a Senior Research Associate of the IASS Potsdam. His research focuses are on sustainable innovation, industrial policy, and governance of the energy transition in Germany and beyond.

The article as been republished from IASS Potsdam.

The ODI report uses a commonsense definition of “subsidy” as actual public cash. The IMF uses a broader definition including non-payment of externality costs: this makes perfect sense to welfare economists, but looks like special pleading to the person in the street.