Legally all former coal fields have to be cleaned up or reclaimed following the end of mining activities. While most former surface sites in Germany are flooded, more sold coal sites are being redeveloped as renewable energy sources. L. Michael Buchsbaum talks to developers to see how it works.

Wind farms could provide new renewable energy sources on the site of former coal mining areas (Public Domain)

Coal mining has left the Earth pockmarked with countless abandoned shafts, open pits and tens of thousands of hectares of disturbed lands from old surface mines.

Though many countries passed reclamation rules requiring mining companies to restore post mined lands back to their original states or approximate original contours (AOCs) after extraction ends, most mining companies have been rather slow to do so. The vast majority of post-mining lands are nowhere near as healthy or bio-diverse as they were prior to industrial activities.

But increasingly, regulators across Europe, along with several energy companies, are redeveloping mined out lands into renewable energy sites. Though solar panels are becoming less uncommon, installing wind farms on former surface mines is still challenging, especially as higher capacity turbines are deployed.

As part of the European Commission’s support mechanism for transitioning away from coal, their Joint Research Centre published a study which looks at the best practices and opportunities throughout Europe, as well as suggestions of financial support (EU coal regions: opportunities and challenges ahead).

The report and developers agree that after a mine closes, converting the site to a renewable energy generation facility can provide new job opportunities and economic value, as well as contribute to a more secure energy supply.

Such projects can greatly benefit from the pre-existenting infrastructure and land availability. The EC report finds that several coal producing regions in Spain, Greece and Bulgaria are particularly well situated for solar power generation while many current coal regions in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland have high wind availability.

Renewable redevelopment in Germany

Throughout Germany the report cites several redevelopment examples. One great success is the Klettwitz wind farm in southeastern Germany, built on former surface mining lands. When it opened in 2000, it was the largest wind operation in Europe; today it includes five separate sections. And following recent upgrades and re-powerings, it has a combined generation capacity of 145.5 megawatts.

Initially the biggest technical challenge of the pioneering project was the construction of turbines on unstable foil above the former pit. Now for almost 20 years, renewable energy has been generated “where previously climate-damaging coal was mined. A brilliant example of the green energy transition,” said Ralf Heinen, CEO of the developer, Ventotec.

Nearby, developer ABO Wind Energy is approaching completion of a wind park on the site of the Lausitz Energie Bergbau (LEAG) owned Jänschwalde open cast mine. The second such project for ABO, it’s the company’s largest to date and they see “enormous potential” for similar brown-to-green undertakings in the future, said company spokesman, Dr. Daniel Duben.

Prior to redevelopment, the site had been a more or less abandoned pit, filled in and awaiting recultivation for future farming. Mining activities at depths greater than 95 meters had left soil layers looser than those found in normal terrain, creating technically demanding construction conditions, ABO reported.

“Though normally foundations for 200-meter high wind systems are only three to four meters in depth, that does not suffice at Jänschwalde,” said Duben. Instead the company used water to flush gravel deeper and then compressed the loose soil. They followed this up by hammering 32 concrete piles, each between 15 and 21 meters long, into the ground to keep the foundations stable. Because of this, the project is more expensive. “Normally it takes less than a year for the wind mills to generate enough energy and income to pay for their installation. It will take a bit longer for the former post mine site because of the size of their concrete anchors,” continued Duben.

Nevertheless, ABO is now targeting similar sites. They view them as classic win-wins since one of the struggles for wind developers is locating sites where they won’t affect local wildlife, bird or human populations. Already impacted and cleared of trees and villages, former mine sites are “ideal” for such redevelopment. Though a handful of other companies are also moving in this direction, most avoid such redevelopment strategies because of the additional complications. But ABO is “keen on developing projects on these sites” because they “strongly believe in the necessity of energy transformation,” said Duben.

However, despite the need to create viable post-mining economies, at present there are no subsidies or technical assistances offered from the state or federal government. In fact “there are more technical and legal barriers to overcome in Germany to build wind farms on former mines than at other locations,” continued Duben.

Back in coal heavy North Rhine-Westphalia, fossil fuel dependent RWE AG has also redeveloped a sliver of their former mine sites into wind farms, in particular erecting the 67-megawatt Königshovener Höhe wind farm on a reclaimed site of their Garzweiler opencast mine.

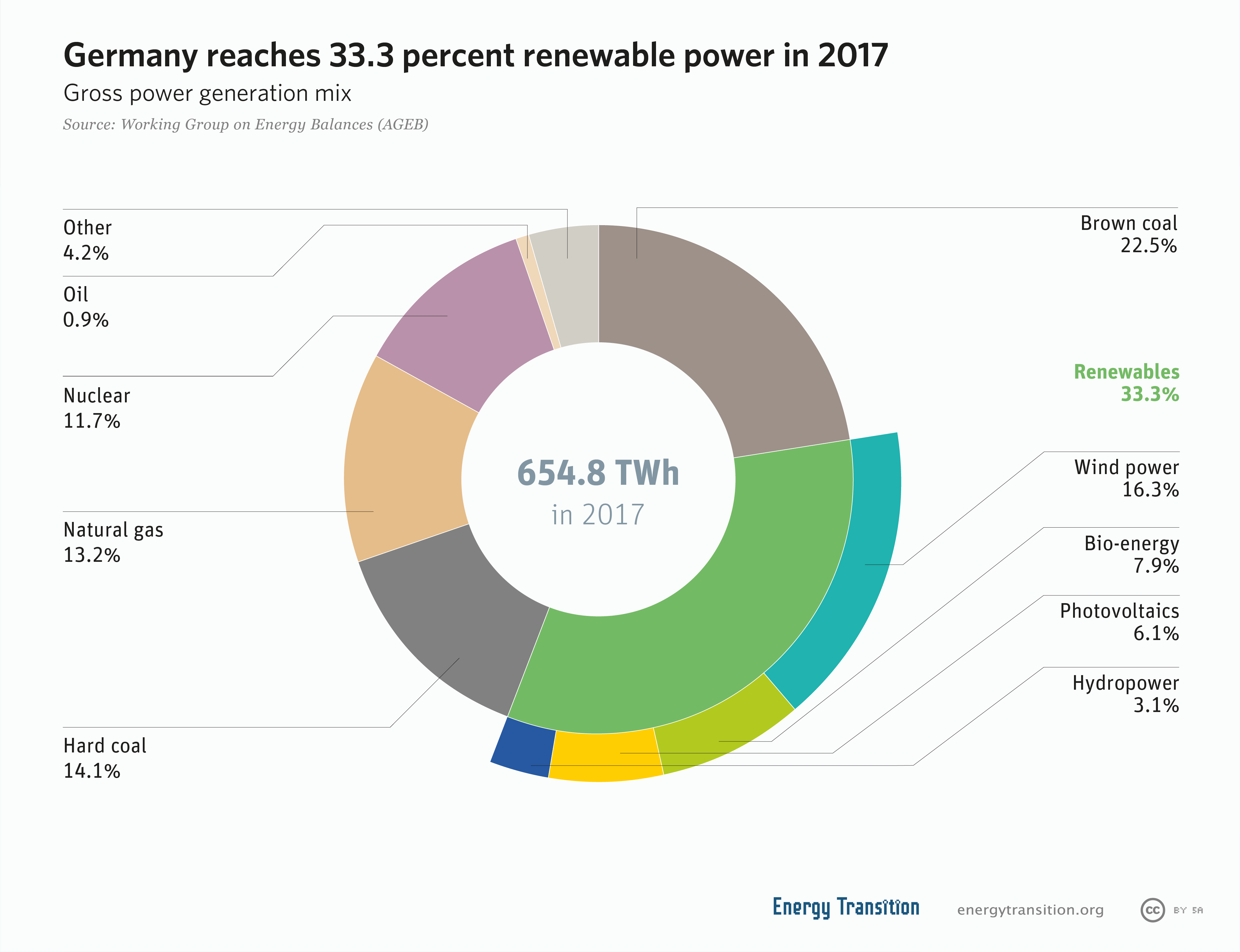

But frustratingly in NRW, only about 12% of gross electricity generation is currently generated from green energies–about half of which is wind, despite the region’s enormous potential. This is in stark contrast to other areas of northern Germany or the country as a whole which is now averaging close to 40% renewable energy.

“Renewable development shifts the policy of the conservative CDU / FDP state government, which after taking over in 2017, is keen to slow down the expansion of wind energy,” said Dirk Jansen, head of the Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND).

Indeed, though the Hambach and Garzweiler pits are virtually surrounded by wind turbines, the gigantic residual holes of the RWE mines are supposed to be flooded after the end of operations, negating any wind energy potential.

Though other possibilities exist, both the state and RWE have been resistant to other alternatives. While Greenpeace Energy proposed to buy out their generating and mining assets and immediately begin redeveloping them into clean energy sites, RWE has stubbornly refused to take another course. But if the Coal Commission’s recommendations are followed, they will have to shift policies or put shareholder value further at risk.

What exactly is the merit of putting wind turbines in a deep hole?