The German Coal Commission has recommended that all coal be phased out by 2038. But this trajectory won’t be quick enough to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, says L. Michael Buchsbaum.

Lignite mining area Gazweiler in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (Public Domain)

Days after the Coal Commission announced their recommendations, the climate activist members of the group held their own press conference to criticize the 20-year exit plan, claiming that although well-intentioned, its slow pace will nevertheless violate Germany’s international climate targets.

A quarter of Germany’s installed coal power capacity will be shut down between 2019 and 2022; the path for the years 2023 to 2029 is much less clear.

(Chart: CarbonBrief)

“Neither the planned final exit date of 2038 nor the vague path until 2030 are sufficient for an adequate contribution to climate protection from the energy sector,” read a declaration by the commission members Martin Kaiser (Greenpeace), Kai Niebert (umbrella NGO DNR), Hubert Weiger (Friends of the Earth Germany, BUND) and Antje Grothus (Climate Alliance Germany/Buir for Buir).

Indeed in their dissenting vote, the four commission members rejected the otherwise agreed-upon timetable. Lamenting that the commission had missed an “opportunity to combine ambitious climate protection with future-proof regional and economic development,” they nevertheless voiced their support for the compromise in general because it broke “Germany’s climate policy stalemate of the past years” and because it creates a phase-out through 2022 while at least recommending the preservation of the still-embattled Hambach Forest.

In addition, the group argued that it is still urgently necessary to specify the exit path from 2023 to 2029. Rejecting both the “non-concrete path from 2023 and the late exit date” of 2038, they fear the lack of concrete planning will “prevent a cumulative CO2 reduction of the energy sector compatible with the Paris Climate Agreement.” On the contrary, “cumulative CO2 emissions in the atmosphere [will be] far too high for Germany to contribute to limiting global warming to a maximum of 2 degrees, let alone 1.5 degrees…In the interest of climate protection, an exit would be necessary by 2030.”

Not progress, but business as usual

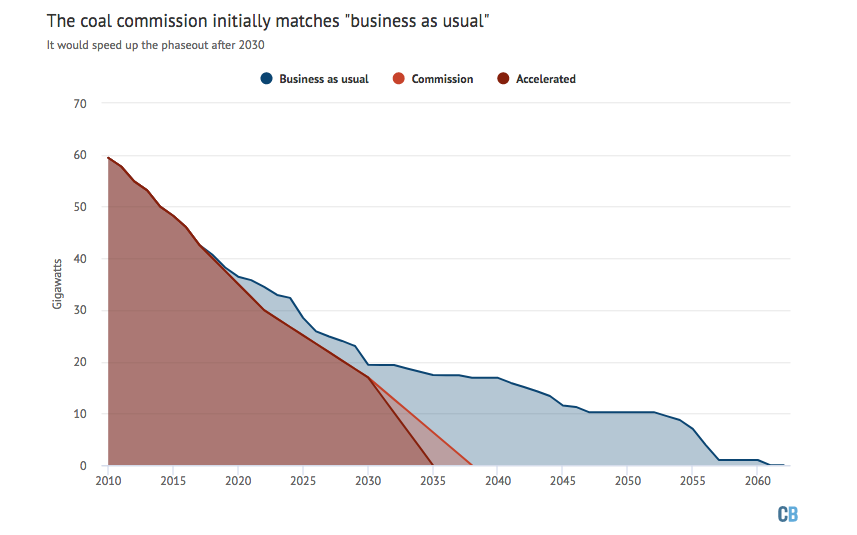

Their fears are backed up by an analysis from think tank Carbon Brief which suggested that coal capacity would barely fall faster under the Commission’s plan than under a business-as-usual (BAU) pathway. The lignite and hard-coal-fired power stations slated for shutdown in the near term are already expected to retire.

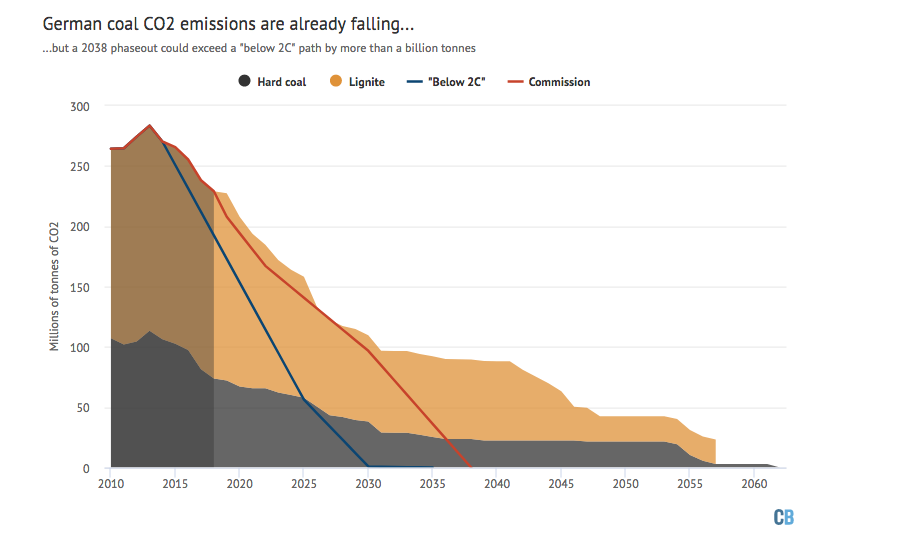

In their analysis, they state that without cutting deeper into planned power plant emissions, Germany will “breach a Paris Agreement-compatible pathway by more than a billion tonnes of CO2.”

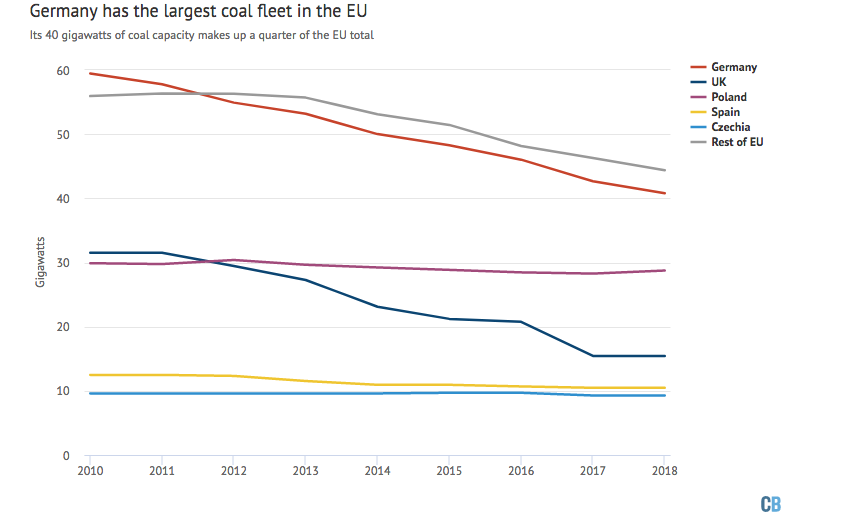

Of course, one of the main challenges is that coal currently supplies nearly two-fifths of German electricity, and has long been the backbone of its generation capacity.With the largest fleet of coal-fired power stations in Europe, Germany also has the fourth-largest fleet in the world, after China, the US and India.

(Chart: CarbonBrief)

The proposed phaseout timeline could actually break EU law: it breaches the deadline for EU coal power to be phased out, as shown in the International Energy Agency (IEA) “below 2C” pathway. Indeed, even an accelerated 2035 coal phaseout would only be roughly in line with the IEA’s 2C pathway, but not its “below 2C” scenario.

In total, the commission’s recommended timeline could prevent a cumulative 1.8bn tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) from entering the atmosphere compared to business as usual, but could still breach the “below 2C” pathway by some 1.3Gt CO2. The 2015 Paris Agreement significantly raised the bar with its target of limiting warming to “well-below 2C” above pre-industrial temperatures and, ideally, only 1.5C. The EU has pledged to raise its 2030 targets and indicated it could commit to a net-zero goal in the longer term.

Critically, according to Carbon Brief, it is only after 2030 that the coal commission’s proposal starts to significantly bend the curve away from business as usual. In other words, it is recommending that forced early coal plant closures mainly take place after 2030, some 12 years into the future. The designated pathway before then really isn’t that ambitious.

The way forward

This looming planning failure seems even more worrying given that in early February Germany finally officially acknowledged that it is also not making the envisioned progress on climate change that had been formerly planned. Though by 2020 Germany is expected to emit around 32% less greenhouse gases than in 1990, the government had previously pledged a reduction of at least 40%. While experts have known for years that Germany would not be able to fulfill these goals (originally set in 2007), the 40% reduction was meant to inspire other EU countries to set more ambitious targets. Instead, Germany’s failure may now inspire other nations to also fail to hold to established emissions pledges. Indeed when combined with the underwhelming ambitions of the coal commission’s emissions recommendations, this admission should signal that Germany’s long-term strategies are simply not working as promised.

(Chart: CarbonBrief)

In announcing the new report, German Federal Environment Minister Svenja Schulze (SPD) called for more courage and commitment to climate policy. She reiterated that she would therefore come up with a law that makes compliance with the 2030 climate goals more binding, something also suggested by the Coal Commission’s environmentalist wing, but ultimately watered down in the final report. As it stands now, by 2030, Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions are planned to be reduced by 55 per cent compared to 1990 levels.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel also backed the Coal Commission’s findings, stating that “by 2038, we want to have exited coal,” adding that “unfortunately we still have too much brown coal.”

However, rather ominously, the chancellor then said that by exiting coal, Germany “will have to use more gas.” The dissenting green commission members and much of the environmental community instead hopes that the planned structural reforms and renewable energy expansion will once again “change the discussion within a few years.” But with fossil gas proving to be as potentially harmful as coal, is Merkel’s climate change solution simply to take Germany from the frying pan into the fire?