To continue leading the Energiewende it started, Germany now needs to follow other progressive nations and announce a swift coal exit. But the “Coal Commission” tasked with structuring the coal phaseout seems to be dragging its feet. L. Michael Buchsbaum takes a look.

Demands by the Greens and other environmental organizations for a quick coal exit have been denied (Photo by Ende Gelände, edited, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Perhaps the most important long-term question before Angela Merkel and the latest version of the Grand Coalition between the conservative CDU and the left-of-center SPD parties is “will Germany continue to play a leadership role in embracing clean energy? Or will it increasingly be eclipsed by other nations?”

At an early stage, the Energiewende forged an international perception that Germany, with Merkel as its titular head, was committed to writing a new green chapter in its long history. Clearly demonstrating that an industrial power can successfully transition away from near total fossil fuel and nuclear energy dependence without sacrificing its economy, today almost 40% of Germany’s energy is regularly generated by renewables.

With ever more capacity coming online, generation costs continue to fall. Likewise, as part of long established plans, the nation remains on schedule to shut its last nuclear power plants by 2022, and this year, after centuries of underground coal mining, Germany’s last “hard coal” mines will finally close.

Though Germany did not create the renewable energy revolution, her early endorsement of its potential turned the tide in green energy’s favor, taking it off the drawing board and bringing it into the real world—simultaneously opening up new economic markets and creating tremendous opportunities.

Leapfrogging ahead of Germany, last year at the COP 23 held in Bonn, over 20 nations, including France, Austria, and Italy confidently joined the UK and Canadian-lead “Powering Past Coal Alliance” to take the next step of pledging to swiftly and purposefully phase out coal altogether. Notably missing, however, were the world’s biggest miners and burners: the US, Russia, China, India and sadly, Germany.

Indeed, despite the Energiewende, today over 40% of Germany’s energy still comes from coal as the nation remains the world’s largest miner and burner of brown coal or lignite – one of the worst greenhouse gas emitting fuel sources. This is a major reason why by March the nation had already exceeded its full-year quota of 217 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

One of the pledges of the new Grand Coalition is the creation of a “Coal Commission” tasked with making the decision of when and how to exit coal. However, its commissioners continue to prevaricate upon when they will even announce that a decision has been reached. Initially it was to be in 2018, then by the end of the year, and now increasingly “sometime in early 2019.”

Moreover, in what some fear a deliberate attempt to slow down its progress, at least four Cabinet ministers with very different mandates will “jointly” work upon it. As currently envisioned, economic minister Peter Altmaier (Christian Democrat), environmental minister Svenja Schulze (Social Democrat), labour minister Hubertus Heil (Social Democrat), and interior minister Horst Seehofer (Chrisitian Social Union) will somehow together steer the work of the officially entitled “special commission on growth, structural economic change and employment.”

But the actual taskforce is being housed in the more conservative economic ministry, signaling that all steerage won’t be equal, and Energy Secretary Altmaier seems to be taking the lead. At the Berlin Energy Transition Dialogue, while praising the Energiewende as a globaly admired business model that other nations should follow, he rejected demands by the Greens and other environmental organizations for a quick coal exit, flatly stating that though Germany “will reduce coal production by half by 2030,” a final coal exit will not occur for several decades more. Note, Altmaier carefully referred to halving the mining, not burning of coal.

Though some coal-fired power plants are indeed being retired this year, these cuts are nothing like what has been done in the UK, which is acting much more like the European leader on climate change. While reducing emissions by more than 40% since 1990, over the last five years alone, they have also slashed coal generation by almost 85%. On April 6, Great Britain experienced its second coal-free 24-hour period since 1882—without blackouts.

But in Germany a key stumbling block seems to be finding a long-term solution for affected industries and the estimated 13,000 to 50,000 affected coal workers (depending on which economic study one accepts). While not a trivial concern, it’s not an impossible hurdle to overcome.

Last December, the European Commission announced that billions of euros of financial support and training schemes to assist impacted coal mining areas are being made available. The new “Platform for Coal Regions in Transition” program is precisely intended to facilitate the development of projects and long-term strategies throughout affected areas, with the aim of “boosting the clean energy transition by bringing more focus to social fairness, structural transformation, new skills and financing for the real economy.”

Maroš Šefčovič, vice-president of the European Commission in charge of the Energy Union, and one of the leaders of this Platform shared several stages with Altmaier as well as other officials at the Berlin Energy Transition Dialogue. At a press conference, both men promised to soon travel to the coal fields of Lusatia in Saxony to meet with members of its state government, and regional union and mining officials with the goal of developing a transition plan. But local mining company Leag has stated that it doesn’t plan to end production at its opencast mines until sometime in the early 2040s.

However, if Germany doesn’t adopt a robust coal exit strategy, not only won’t it be able to meet its promised emissions targets, but the goals of the Energiewende may go up in smoke along with hundreds of millions of tonnes of filthy lignite. Allowing for a slow burn will actually suffocate the green energy revolution while cowardly leaving an ever growing toxic mess for the leaders of other nations and future generations to clean up.

“today almost 40% of Germany’s energy is regularly generated by renewables.”

CLEW for example states that renewables account for 13 % of Germany’s energy consumption and fossil fuels about 80%. The rest is nuclear.

https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/germanys-energy-consumption-and-power-mix-charts

“today almost 40% of Germany’s energy is regularly *GENERATED* by renewables.”

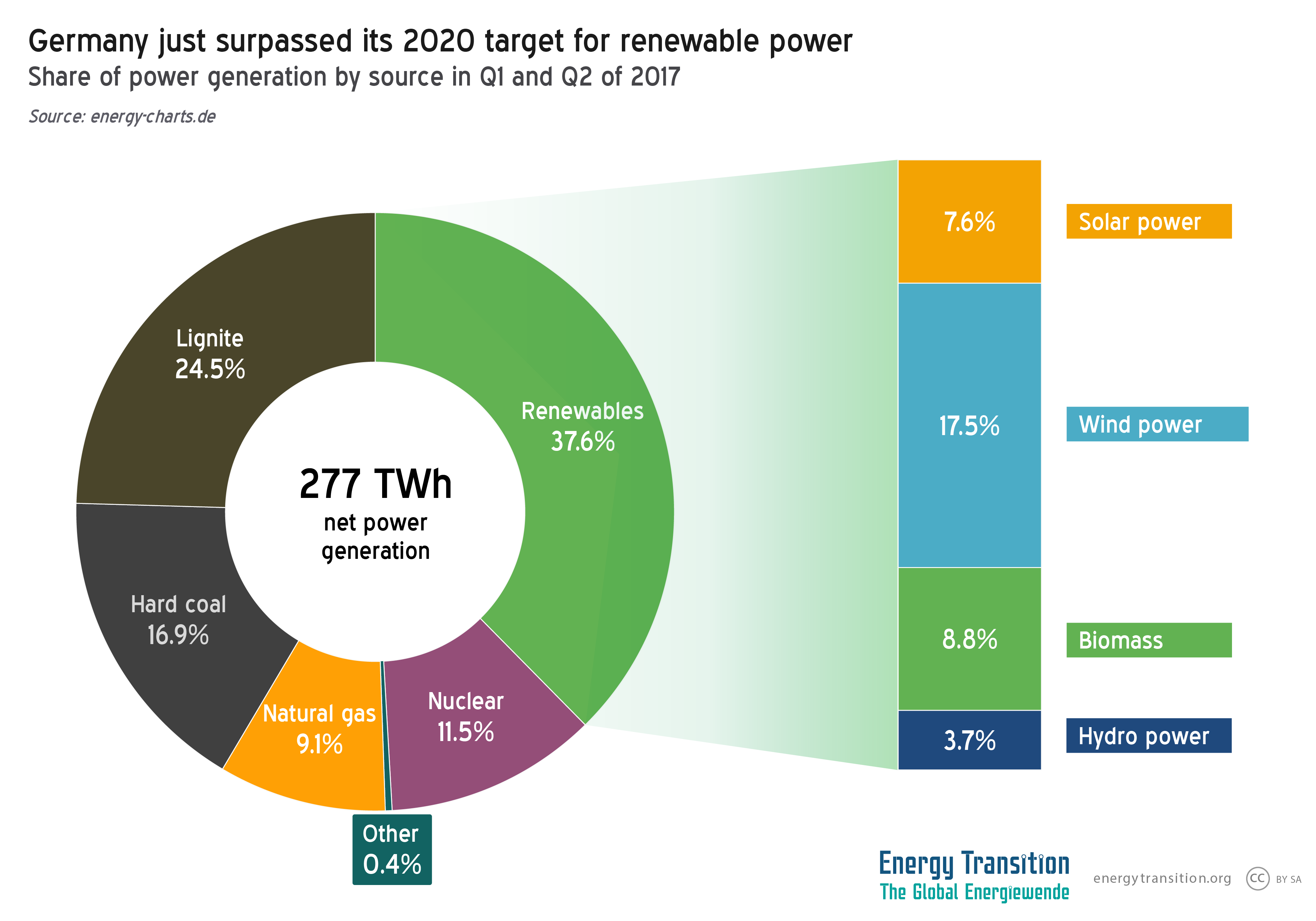

Power consumption does not equal power generation. Generation last year was 37.6% renewable – see chart in this article, sourced from energycharts.de

“…today almost 40% of Germany’s energy is regularly generated by renewables.”

…and a comparable comment regarding coal.

No, they’re not! Till about twenty years ago, the equation of power with (all) energy was understandable, among the non-cognoscenti anyway. Now, it’s a hanging offence. While Germany does have renewables projects for destinations other than electricity, and while the sole saving grace to its recent sqirming away from its erstwhile headline heroics in terms of power transition targets has been an apparently greater emphasis on transition in the non-electrical modes, it has reached nowhere near 40% of renewables for all energy. Without checking, I would be reasonably confident that it is still below 20%. (Love to learn I was wrong about that.) For most substantial countries, 15 – 40 % would encompass the range of electric power as a proportion of total energy consumption – I think it’s about 25% for Germany. Of course, one way of addressing transition in other modes is to bring them into the ambit of electricity, e.g. the electrification of transport, now with a rising profile.

See the chart – 37.6% renewable power generation. Share in final consumption is different, and we have addressed that in multiple other articles on this site.