On August 21, a solar eclipse will pass over the continental United States. Attention is now being paid to the impact on solar power generation. Germany’s solar eclipse of 2015 provides some answers. Craig Morris says the impact will be negligible.

The US eclipse won’t change much today – but it could once countries increase their solar power (Photo by Takeshi Tuboki, edited, CC BY 2.0)

On 20 March 2015, a solar eclipse passed over Germany, which had the most photovoltaics installed of any country at the time. There was a lot of concern at the time, and I reported live from a grid operator that day.

Worse case #SolarEclipse for PV: south Germany is cloudless where most PV is instaled, hold on tight pic.twitter.com/CUGuynYUaT

— Craig Morris (@PPchef) March 20, 2015

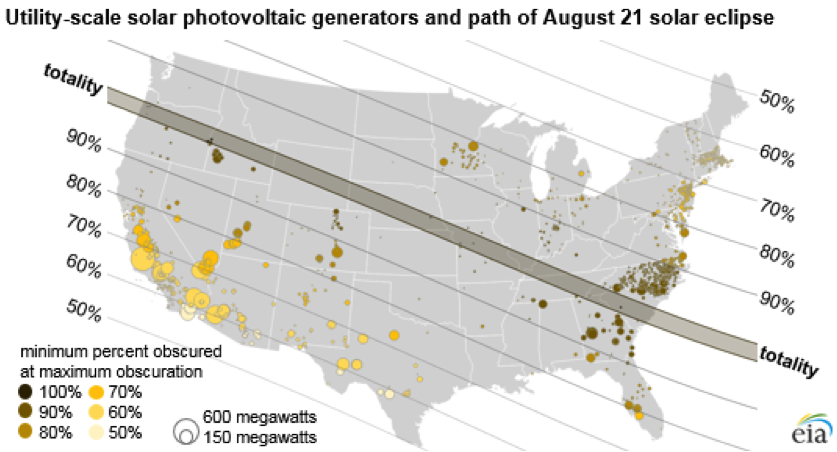

California has the most solar of any US state, but it lies safely south of the full eclipse. An impact might be felt in the afternoon in North Carolina – the second-biggest solar state – and Georgia, which comes in eighth. Then again, the eclipse will peak at around 2:30 PM there, when solar power is already dropping.

However, the grid operator in North Carolina is playing it safe by switching off large solar plants entirely in advance. California is asking residents not to switch on lights during the eclipse, thereby increasing power demand right when solar power supply drops.

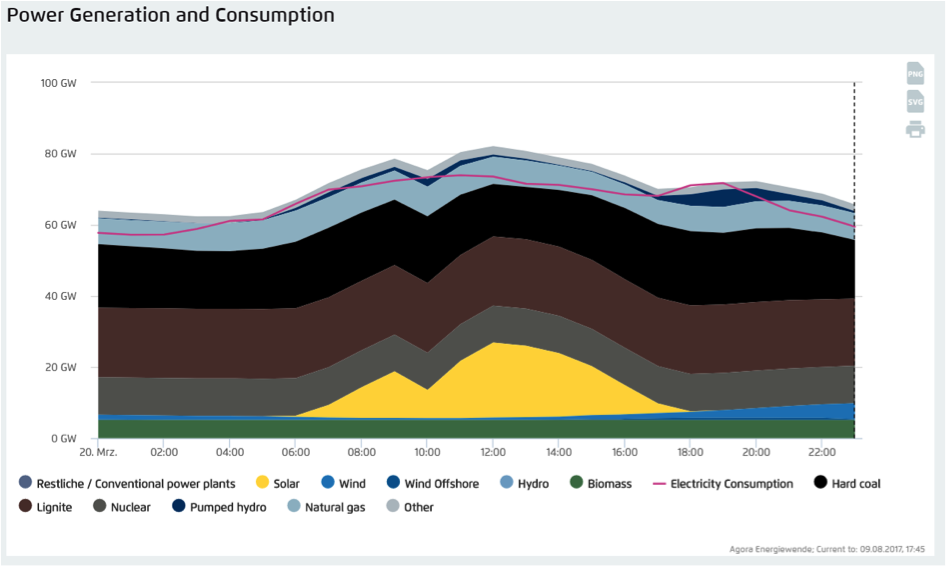

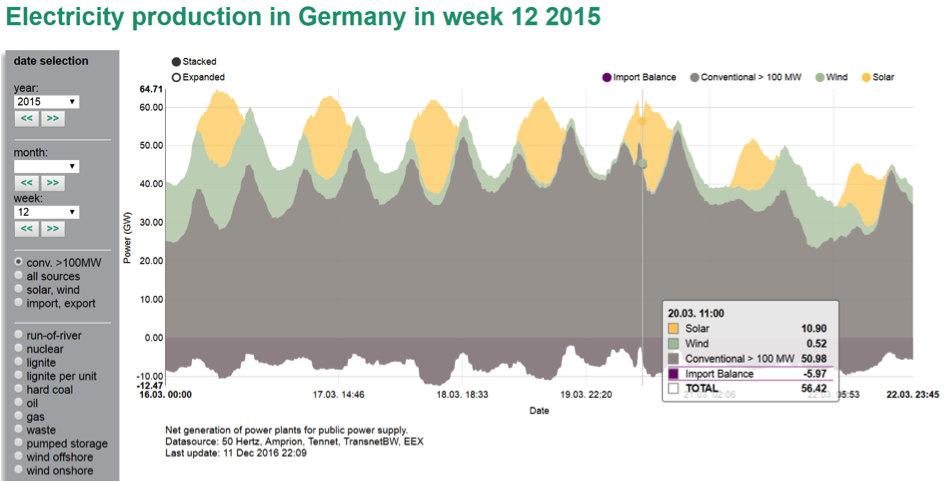

A look at Germany’s experience from 2015 suggests that demand might not rise during the eclipse. In Germany, a lot of people stopped work (it was a Friday) to witness the event outside. The chart below shows what that day looked like. The eclipse peaked at around 10 AM.

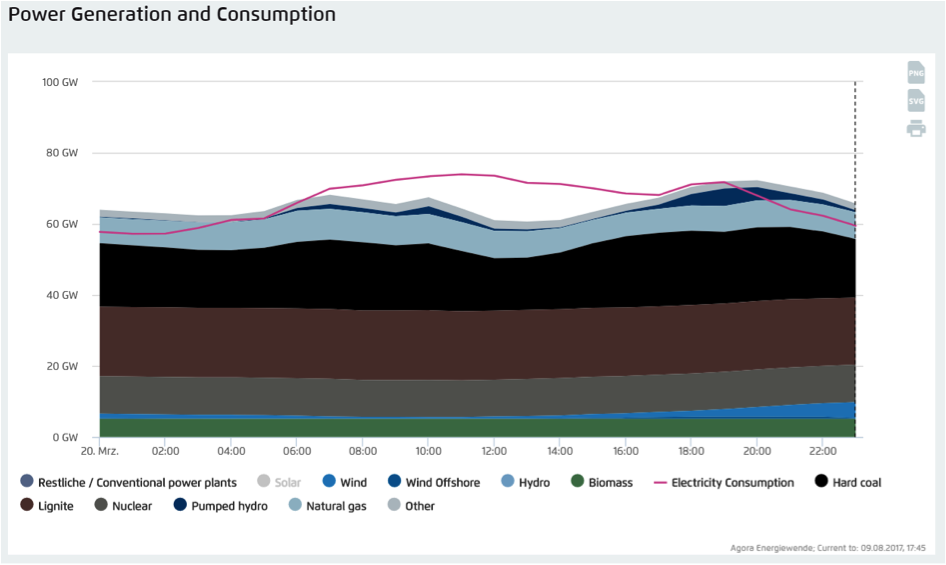

Note before we continue that the red line indicating power demand remains below total generation throughout the eclipse, meaning that Germany was a net exporter during those hours – we’ll come back to this below. But first, if we remove solar power from the chart, we can see how little everything else reacted (play around with the interactive website here).

It’s impossible to see the eclipse here at all. Instead, we see a slight decrease in conventional power generation just after noon as solar comes back, followed by an increase towards the evening as the sun sets. But this does not look challenging; nuclear and brown coal plants hardly move at all. These facts are important because of exaggerated claims like this one at Vox.com:

Germany stabilized its grid and electricity supply by dialing up its fossil fuel, nuclear, and hydro power, while also asking four energy-hogging aluminum smelters to dial down their power use temporarily.

In reality, conventional power generation fell (!) during the heaviest parts of the eclipse between 10 AM and 11 AM. And while smelters were asked to reduce power consumption, a report from Germany’s transmission grid operator (the country has four) explained that these steps were not actually necessary, but merely an attempt “to test this option for future challenges.”

If we now include power trading, we see what really happened (mouse over the original website for yourself). Net exports fell from 7.5 GW at 9:30 am to 2.2 GW at 10:30 am, a difference of 5.3 GW. During that hour, solar generation fell from 14.4 GW to 6.0 GW or 8.4 GW. In other words, Germany simply briefly reduced its net power exports (below the baseline in the chart) during the eclipse.

(Source: Energy-Charts.de)

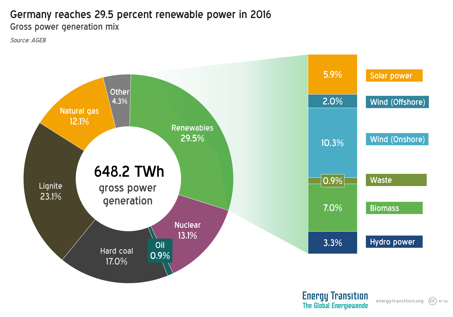

The Vox article overstates the impact on Germany by claiming: “For a country whose electricity is 40 percent powered by solar, it was hit hard.” In fact, Germany was not hit hard at all – and solar power production sometimes peaks at 40%, but solar only makes up 6% of power supply in Germany.

In 2016, North Carolina got 3.25% of its power from photovoltaics, just over half of Germany’s 6% in 2015. While the eclipse in Germany was not total, the impact in North Carolina will hardly be larger in light of the state’s smaller share of solar. Below is a visualization of the 2015 eclipse in Europe.

In the end, all of this is far less exciting than the press makes it out to be. We had the same inflationary reporting on the 2015 eclipse, which turned out to be a nothingburger. I’m with my colleague Christian Roselund: no panic necessary – but maybe decades hence. Countries with far larger shares of solar in the future will not be able to rely on power trading during eclipses like Germany did two years ago.

In 2015, Italy switched off its big solar plants like North Carolina plans to. Germany did not. Its experts wanted to use the event as a preparatory exercise. As such, the impact was almost too small because the conventional fleet hardly had to react. On the other hand, the next total solar eclipse in Germany won’t take place until 3 September 2081. By that time, it’s anyone’s guess what options we will have.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.