The German chapter of the Green Party may be the strongest in the world – so how is it faring in numerous coalition governments? Can other countries with different political systems learn from the German experience? Craig Morris explains a new study.

The German Green party has been exceptionally successful on a local level. (Public Domain)

The German Greens – officially called “Alliance ‘90/the Greens” – are just barely alive, one might think looking at recent polls, which put the party just barely above the 5% of the vote needed to be in parliament. And aside from 1998-2005, they have never been in a coalition government, nor are they likely to be after the elections coming up this fall. So they are marginal, right?

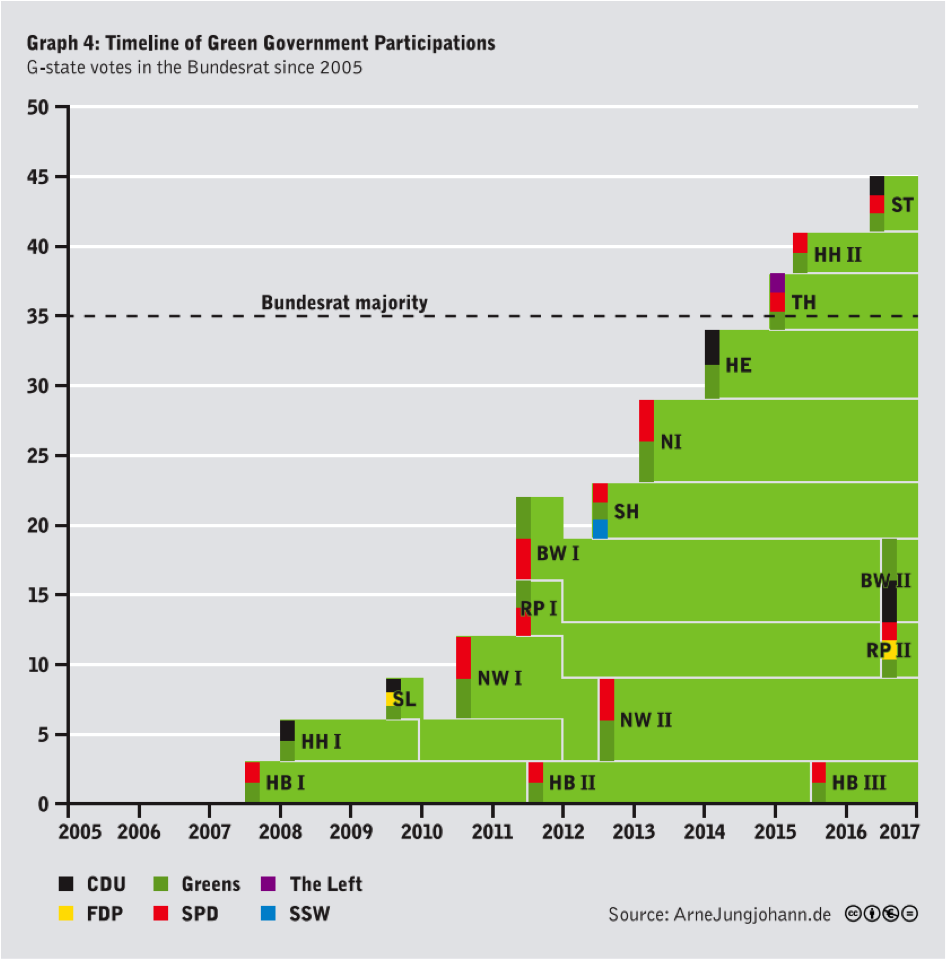

Not so fast. Look below the federal level, and the Greens are everywhere, generally as junior partners in coalitions. As the chart below shows, Merkel’s grand coalition has to anticipate the reaction of the Green Party because the Greens are in a majority of state coalition governments.

To understand the chart above, it helps to know that the Bundesrat is the upper house representing the governments of Germany’s 16 states. So when the Greens were voted out of Gerhard Schröder’s coalition in 2005 (based on votes in the lower house: the Bundestag), the Greens were not in government at the state or federal level for two years. But since 2007, they have gradually re-entered state coalitions in 11 of 16 states.

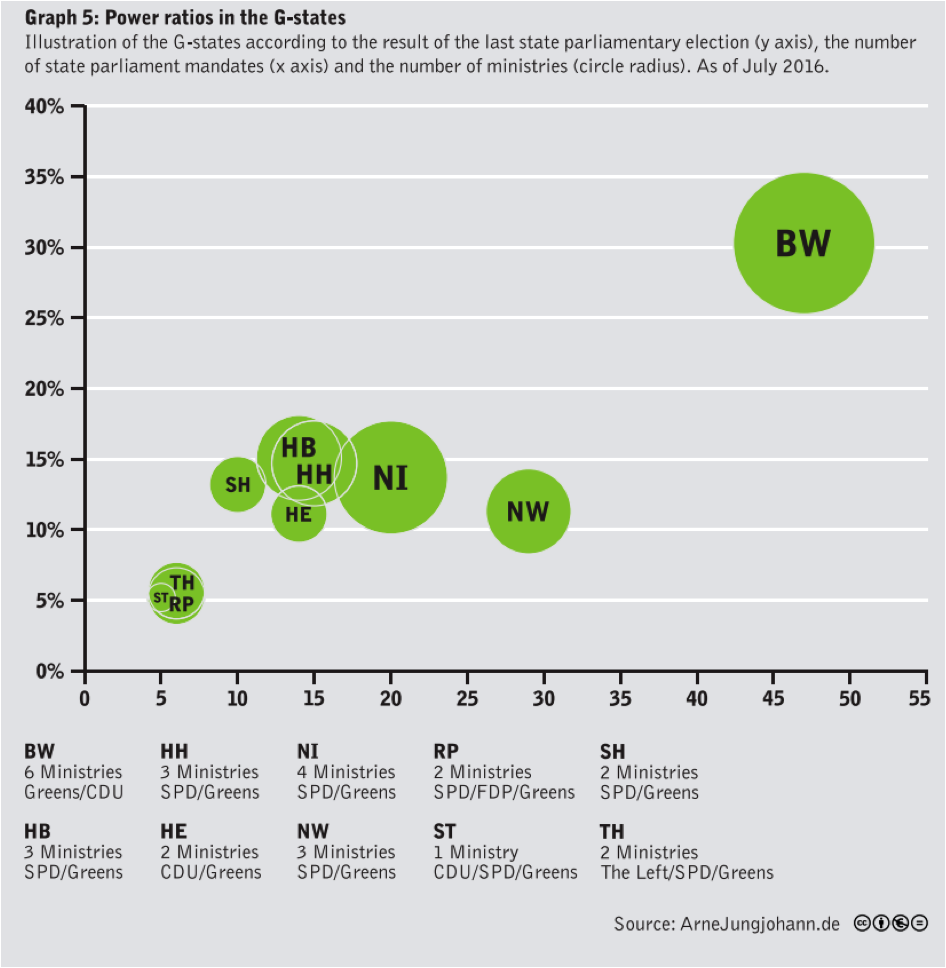

As much as I like the chart, Arne Jungjohann, its creator and the author of the new study entitled “German Greens in coalition governments” (PDF), warns that it should not be misinterpreted to mean that the Greens alone have a majority to block Merkel’s coalition. Rather, the Greens are in coalitions that can do so, as the chart below indicates.

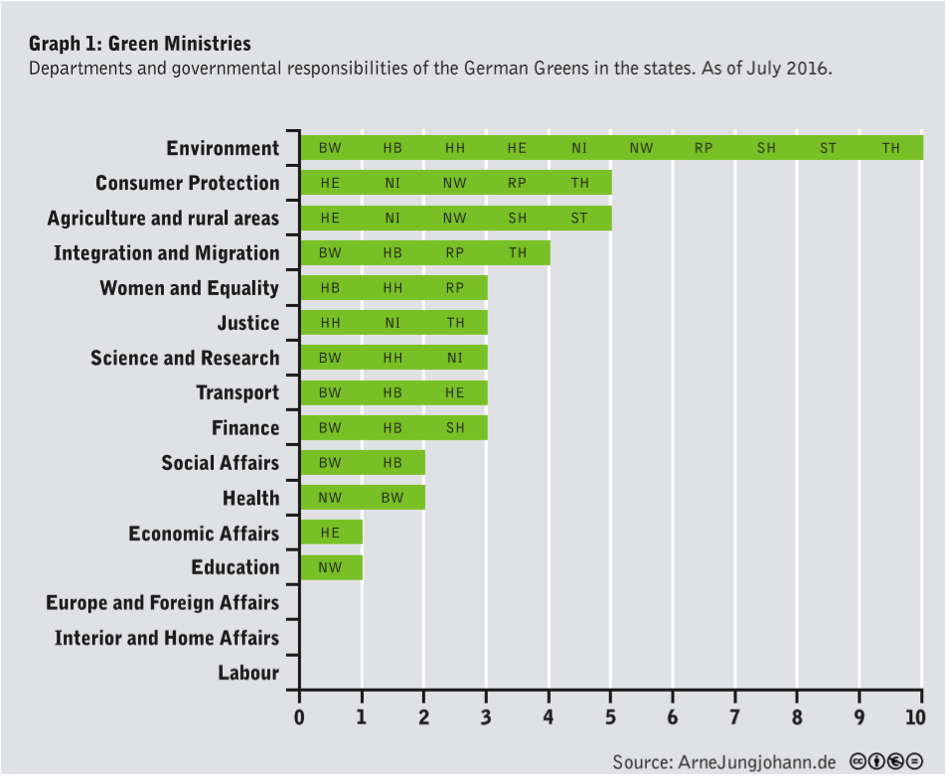

At the bottom of that chart, we see how many ministries the Greens also direct. The chart below shows specifically what fields Green politicians are entrusted with. The key finding isn’t a surprise: the Greens generally are in charge of a state’s environmental ministry, with consumer protection and agriculture coming in second.

But interestingly, the Greens also lead ministries for finance, justice, transport, and science and research. “The main takeway for me,” Jungjohann told me, “is that the Greens are diversifying beyond traditional green issues. They are increasing their capacities and expertise in a growing number of fields.” There are only three policy areas the Greens currently do not cover: European affairs, home affairs, and labor.

The study’s main focus is a bit harder to visualize in a graphic: how are the Greens navigating coalitions with so many different party constellations (five)? The Social Democrats and Christian Democrats have managed a similar situation for decades, but it’s new for the Greens.

Jungjohann’s study comes at a time when the Greens are just setting up structures to coordinate actions with different political partners. He had a nose for this hot topic because he served as a strategic advisor to Germany’s only Green Minister-President (a sort of combination between a state governor and state senator in the Bundesrat), Winfried Kretschmann.

So what did the Greens do? To find out, Jungjohann interviewed decision-makers within the party. He found that coordination became crucial by 2011, when the Greens became the bigger coalition leader in Baden-Württemberg. They formed a classic “coalition committee” like the ones in other parties. But each coalition remains tailor-made; there is no silver bullet.

Lessons for other countries?

One question in the United States is whether the focus of political action should be on the local or federal level, especially for third parties. The story of the Germans Greens suggests that a party can develop a federal impact from bottom-up success stories. But Jungjohann’s main lesson from presenting the material internationally is different:

“Many Greens internationally see their role in building up grassroots networks and staying away from dirty compromises and other parties – stay clean in the opposition instead of getting hands dirty in power. The German Greens are in stark contrast: they are more pragmatic, working within the system to form coalitions with all parties (outside right-wing populists), a strategy that many international Greens reject.”

But only, of course, if the political system allows small parties to have an impact. In a winner-take-all system, small parties remain marginalized. Germany’s political system is also designed to produce consensus; each party sees most others as a potential coalition partner. Indeed, the Greens are already in coalitions at the state level with 4 other parties, one more than is currently represented in the Bundestag. So the Greens already have experience with every possible federal coalition candidate at the state level.

Incidentally, the name “Arne Jungjohann” may sound familiar to my readers. He helped me create this website back in 2012 and is my co-author for Energy Democracy. A live stream of a presentation of the study in Liverpool can be viewed here.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Good stuff.

The post talks about the “local” level, but in fact only covers the Länder. How many municipalities have a Green mayor? I get the impression that German cities lag in the global green movement exemplified by the confusingly named C40 group of big cities, now up to 90 members. Where are the low-emission zones? Am I wrong here?

That’s right, James. German Greens on the local level are organized in this network: http://kommunalwiki.boell.de/index.php/Gr%C3%BCne_Kommunalpolitische_Vereinigungen