As the Nord Stream II project progresses, many EU countries – and Brussels itself – continue to express concern. So why is the German government so nonchalant about the country’s dependence on natural gas from Russia? Craig Morris has a few suggestions.

The planned pipeline – a liability or a geopolitical strategy? (Photo by Pjotr Mahhonin, edited, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In a recent post, I talked about how the Dutch aim to discontinue gas sales to Germany altogether by 2030. Gas from Norway is also drying up; the IEA expects Norwegian gas to decline by as much as 40-50 percent by 2025. In the long term, dependence on Russian gas and possibly liquified natural gas (LNG) from further away might become necessary. Germany does not have any LNG terminals, however, and is not planning any. That leaves mainly Russia, which explains the interest in Nord Stream II, another pipeline to connect Germany directly with Russia via the Baltic.

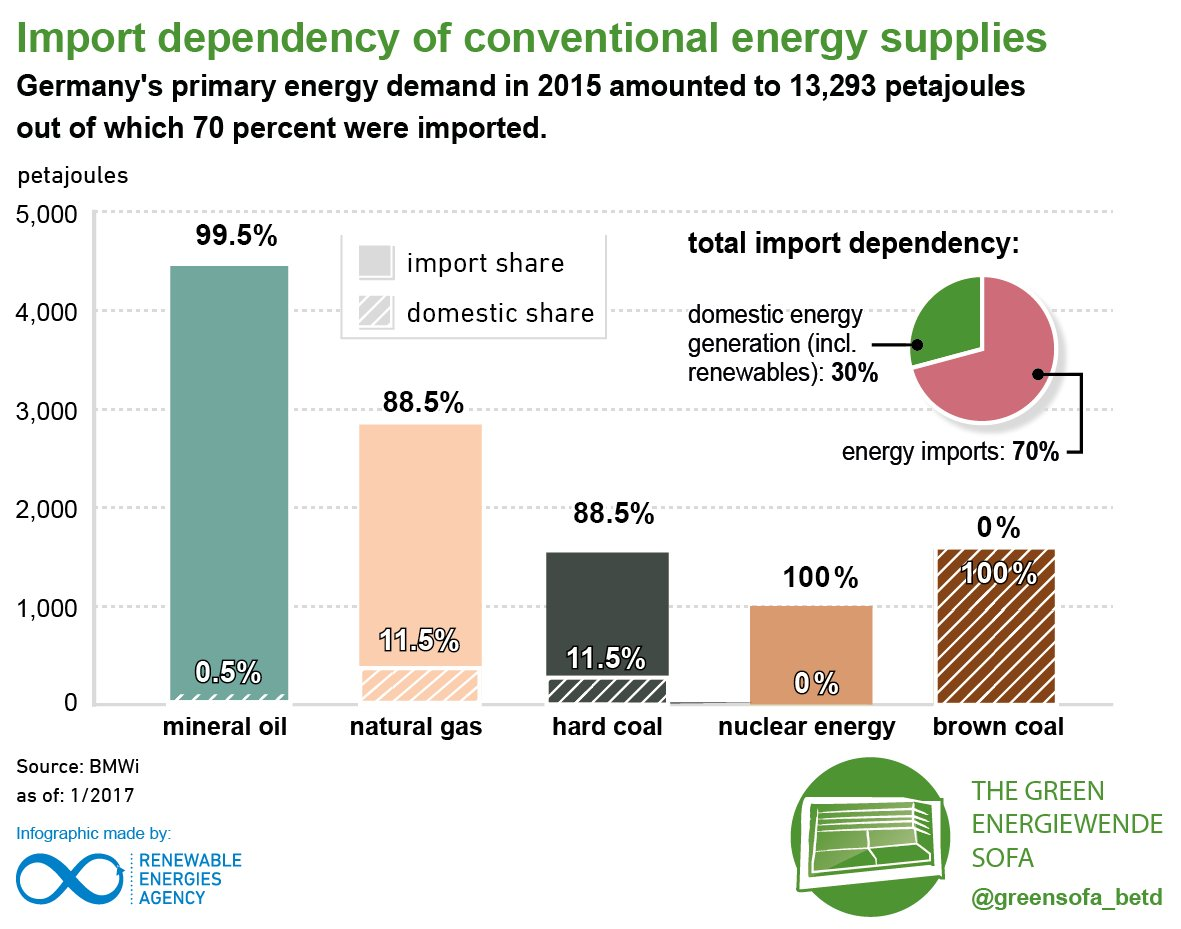

Germany only covers around an eighth of its own gas consumption, but the situation will get worse: that amount could approach zero by the beginning of next decade as German resources run out. (Source: AEE)

In light of conflicts over gas between Russia and Ukraine, relying on Russian supplies can be viewed as a geopolitical weakness. On the other hand, Germany has long imported lots of Russian fossil fuel from Russia, including during the days of the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Yet, German decision-makers seem convinced that Nord Stream makes Russia more dependent on Germany / Europe than vice versa.

They may be right. Germany was Russia’s third largest trading partner in 2012, when Russia was only Germany’s eleventh. Germany is less reliant on Russian gas, the logic seems to be, than Russia is on revenue from Germany. Berlin is thus pursuing a soft-power approach: entangle Moscow and Gazprom in normal business deals to bring them closer to western Europe.

What about Ukraine?

But doesn’t the crisis in Ukraine show that Russia can’t be trusted? One aspect is often forgotten in this tale: Moscow stopped supplying gas supplies to Ukraine because the Ukrainians wanted to keep the “friendship price” (the official term) at a fraction of the market price, which Germany pays. Furthermore, Wintershall, a subsidiary of German chemicals giant BASF, has had joint ventures with Russia’s Gazprom, as have other German firms. In addition, up to 2005 then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder promoted the Nordstream pipeline directly connecting Russia and Germany; he is now a board member at Gazprom and chair of Nord Stream II.

The German government’s continued willingness to import Russian gas leaves other European countries scratching their heads (also see Nord Stream’s Wikipedia page). But the Germans clearly believe that close business relations with Russia are less a security risk than a shrewd tactic to ensure peaceful interdependence. Press reports indicate that Germany is linking the Nord Stream project to Ukraine; Berlin is telling Moscow that German will stop buying gas if Russia cuts off Ukraine again.

To understand this issue better, I contacted Severin Fischer at the Center for Security Studies in Zurich. In a recent paper (PDF), he argues that the EU has called for market competition, and that’s exactly what they are getting with Nord Stream, which is not financed with public money. “The idea of a market economy implies,” he writes in his paper, “that every actor should have the right to take risks and dump money, as long as this is not public money.”

Fischer told me that my reading of Nord Steam as an attempt to create interdependence for peace, which he sees as standing in the decades-old tradition of Social Democrat rapprochement towards Moscow (called Ostpolitik), is generally correct but not central. Rather, “the project makes Germany a central hub for gas in the EU. Ukraine has already largely switched to imports of gas, including Russian gas, from the EU, but not from Russia directly.”

He nonetheless feels that Nord Steam II goes against some visions of what an EU “Energy Union” could look like. “There seems to be no legal basis for Brussels to stop the project, but that doesn’t mean Germany’s neighbors will be happy with the deal.”

Meanwhile, he points out, Ukraine aims to act as a transit country for Russian gas without consuming any of the gas itself. “The arrangement will allow Ukraine to set its own price for transit. Russia won’t like being on the short end of that stick.”

In other words, Nord Stream ties Moscow to Berlin and makes Gazprom play by market rules – but it also causes strife elsewhere. It’s hard to say how Germany’s gambit will play out over the long term.

For more details, see these recordings of a recent conference on Nord Stream held by the Bruegel think tank.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of Global Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

[…] Nevertheless, only half of this capacity has been used, and with the construction of the Nord Stream pipeline, the transit role of Slovakia is decreasing, as are the revenues from this gas […]