Green MEP Claude Turmes has led some of Europe’s key energy and climate policy reforms since 2000. Now for the first time in a book, launched in Brussels on 1 March, he explains how and why Brussels has pioneered – and obstructed – the energy transition in Europe. In an exclusive interview with Energy Post, Turmes gives an insider account of dreams, lobbies, and political, economic and social realities.

Claude Turmes on the EU (Photo by Jwh, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0 LU)

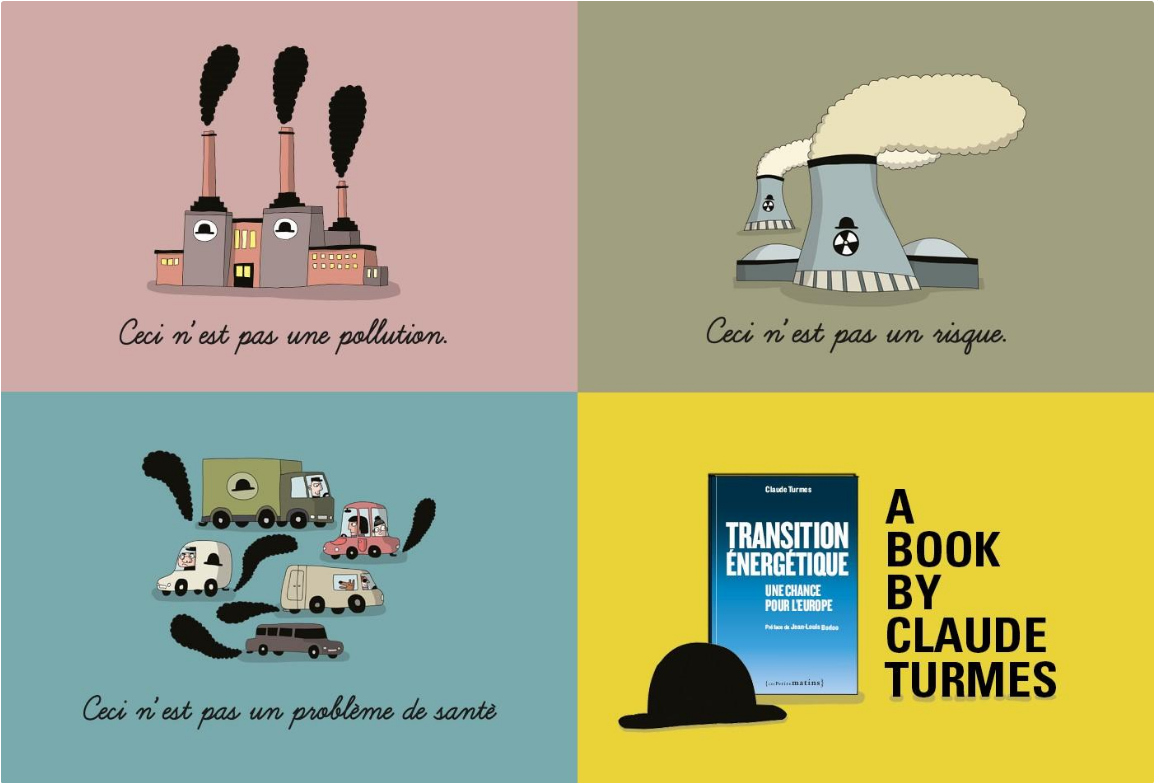

On 1 March 2017, Green MEP Claude Turmes launched his book Transition Energetique: Une Chance Pour L’Europe (Energy Transformation: An Opportunity for Europe – the English translation is in progress) at the Magritte Museum in Brussels. This book is full of original insights on how EU climate and energy policy came about and what we can still do to shape the future.

Speakers for the evening are a who’s who of Brussels energy policymaking, including current EU climate and energy commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete, former EU energy commissioner Andris Piebalgs, president of the European Parliament’s energy and industry committee Jerzy Buzek, former French and Danish environment ministers Jean-Louis Borloo and Martin Lidegaard and … Johannes Teyssen, the CEO of Eon.

Turmes accuses a high-level lobby group created by some of Europe’s biggest energy companies in 2013 of trying quite simply to destroy EU climate and energy policy

This is a book about what has happened in EU climate and energy policy over the last 15 years – and why – and what should come next, written by a man who has been one of its chief architects.

Claude Turmes joined the European Parliament back in 1999 as a Member of the Greens for Luxembourg and rose to become its number one energy specialist. Roundly respected by colleagues from all political groups, he became rapporteur, or the Parliament’s lead negotiator, for key pieces of European energy legislation such as the second electricity market liberalisation package in 2001 to the EU renewable energy directive in 2008. Some of the concepts that we take for granted today are originally his idea: “nearly-zero energy buildings” for example.

Now Turmes has written a book. Because we are at “a decisive moment” to decide the next decade of EU climate and energy policy. In this exclusive interview with Energy Post, he offers a sneak preview of his new tome (477 pages). It’s a good story, with villains and all. Turmes accuses a high-level lobby group created by some of Europe’s biggest energy companies in 2013 of trying quite simply to destroy EU climate and energy policy. This so-called Magritte Group – hence the book’s launch at Brussels’ famous Magritte Museum – is in his mind the main reason why so many in Europe today see the energy transition as a burden rather than “what is probably one of the biggest opportunities for the European economy”.

For Turmes, the future of energy lies in renewables, energy efficiency and interconnectivity. The energy transition is as much about the democratisation of energy as about greening, industrial leadership and job creation. For him, renewable energy auctions are only viable if they enable citizen participation. He isn’t ready to scrap the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) and instead looks forward to a carbon floor price, which he believes Germany will support after its elections this autumn. He isn’t ready to give up on nationally binding targets for renewables and energy efficiency either. “Investors tell me that binding targets and stable support schemes are the best way to reduce capital costs.” The big challenge going forward however, is the phase-out of coal and nuclear.

Traditional utilities can play a constructive role in the energy transition, Turmes says, provided they are ready to transform their asset base and business models. He is thrilled to have the CEO of Eon – the company is leaving the Magritte Group – at his launch. For him, this is living proof not just that an energy transition is possible, but that it is happening.

Q: Why have you written this book and why now?

A: Because we are at a decisive moment of planning and deciding Europe’s energy and climate policy for the years ahead. It’s a book to allow more people in Europe to understand where we are coming from and where we should go to.

Q: So are we today at a key moment in the energy transition?

A: Yes, since 2000 the EU has given a much bigger impulse to the energy transition than is apparent to certain people. It’s about explaining to citizens, national policymakers and stakeholders at large what the EU has done through legislation, research funding etcetera to bring forward what will be the future of energy – renewables, energy efficiency and greater interconnectivity. I show what has been achieved and give an analysis of the big trends to come and who the main actors are.

I think a big difference today compared to 15 years ago is that then it was much more about [national] governments, the European Commission and the European Parliament. Today we have actors like cities engaged in a bottom-up movement. We have more possibilities for citizens and cooperatives to engage in their own personal energy transition.

Q: You’re very critical of the traditional utilities. Do they have a role to play going forward?

A: Outside of a few energy companies – such as Dong in Denmark, maybe Eneco in the Netherlands and smaller ones like Ewe in northern Germany – all the others were not able to anticipate the energy revolution. Their first reaction was “let’s stop it” and the creation of the Magritte Group was all about that. It has lobbied at the highest level – prime ministers, European Commission etcetra – to destroy the European framework for the energy transition.

What is becoming more apparent now is that if energy-intensive industries oppose all change and refuse to pay for anything this destroys the business of innovative energy companies

Now I have the impression however that more and more energy companies understand that this change will happen anyway and it’s their last opportunity to join. Or risk Kodak’s fate.

Q: Could the traditional utilities play a constructive part in the energy transition?

A: Yes. Dong, which basically produced electricity from coal, is today the world’s largest offshore energy player. EnBW, who basically only did nuclear in Germany, is now moving over to renewables and grid-led energy efficiency. Eon and RWE, which are among the most influential and biggest companies, have split up on the basis of an analysis that the old energy world (coal and nuclear) is dead and there is a new energy world (energy efficiency, renewables and the grid) in which you have to be fast.

Q: How do you see the Magritte Group positioning itself today?

A: They have played a very, very negative role over the past years. In my analysis, their lobby explains why a lot of policymakers and even [former European Commission President] Barroso started to be negative about what is probably one of the biggest opportunities for the European economy – to be a leader in the energy transition.

What is happening now is that certain members of the group are leaving. I think one of the thrilling parts of the launch evening for my book is that Johannes Teyssen, head of Eon, a long-standing member of the Magritte Group, is taking part. He has decided to leave the group. Eon and the Magritte Group are no longer a good fit for one another.

Q: In the book, you also talk about an alliance between energy companies and energy-intensive industries. How do you see that today?

A: I think there was a moment when they were really fighting together to destroy/weaken EU [climate and energy] legislation. What is becoming more apparent now is that if energy-intensive industries oppose all change and refuse to pay for anything – and these industries consume almost a third of all electricity in Europe – this destroys the business of innovative energy companies.

When I see the result of the EU ETS [Emission Trading System] vote in the European Parliament last week, which was the result of very intense lobbying sectors like cement and steel, I think one of the major stumbling blocks to move ahead is the refusal of energy-intensive industries to recognise that the energy transition is much more of an opportunity than a threat to them. If you build wind turbines, you will sell more steel. If you insulate buildings, you will sell more chemicals. I don’t understand why the CEOs of these companies continue to oppose climate change policies.

Q: Some people say that the energy transition is simply too expensive to realise.

A: The good news is that renewables were expensive but they are not anymore. The latest (joint) PV tender between Germany and Denmark ended up at €55/MWh. We have offshore wind tenders at €49/MWh. Today, new renewables investments are cost competitive or cheaper than the alternatives. From an economic rationale, you would go to 100% renewables as fast as possible.

The slowdown comes more from protecting old assets, especially our huge overcapacity of coal and nuclear in the electricity sector. We also have old assets in the transport sector – Dieselgate is all about this – the car industry in Europe is refusing to move into fossil fuel-free transport. And when it comes to housing, we have the fight against oil and gas heating systems. In a certain sense, the game now is no longer about how fast we can go into renewables and energy efficiency, but how fast we can phase out old energies to create space for the new ones.

Q: What are your expectations for the European Commission’s Clean Energy Package? This doesn’t propose any phase-outs.

A: The proposals on the table are partly the consequence of the Magritte Group lobby and the attitude of too many policymakers that this energy transition is a burden. What I try to show in my book is that this is not about sharing a burden, this is about sharing an opportunity. Europe has for too long spent billions buying oil, gas, coal and uranium from outside. This is an opportunity to create jobs and added value inside Europe.

Re the proposals, I think we need to be more ambitious on energy efficiency and renewables and we need to put the disussion over the phase-out of coal and I think also nuclear, on the agenda.

Q: Would it be feasible to phase out coal and nuclear power at the same time?

A: I think [the problems at] Tihange, the Belgian nuclear reactor, has already put that on the agenda. For a citizen living in a border region, the risk coming from a nuclear reactor in a neighbouring country is much more intrusive than any EU legislation. It is a bit hypocritical to have an Energy Union which wants to address everything but the risk from the nuclear industry.

And if we take the Paris Climate Agreement seriously, we need a phase-out plan for coal. I have recently seen some figures that say we need to get out of coal by 2030. One of the missing pieces in what the European Commission has put on the table is too few ideas on how we can help those regions in the coal business. In the 2017 State of the Energy Union report we need a concrete proposal for how to organise the transition away from coal in today’s coal regions.

Q: The EU has imposed a shift in renewables support from feed-in tariffs to auctions. What do you expect from this and from a fresh review of EU state aid guidelines due this year?

A: We will have to monitor the success but also the difficulties that arise with auctions. I think there is a big question mark over whether they will allow citizens, cooperatives and cities to take part. A second issue is the insistence of some civil servants in DG Comp [the European Commission’s competition department] to impose technology neutral auctions. I think one of the big battles will be to force DG Comp to drop this absolute claim of technology neutrality. [Ed: each renewable energy brings something different to the energy system.]

Maybe auctions can be part of the game, but there are two conditions for me: one, technology specific auctions and two, there must be an easy way for citizens and cities to take part to pursue the bottom-up energy transition. I think that the European Parliament and governments should enshrine some principles such as technology-specific tendering and opening a space for small investors [in the new EU renewable energy directive].

Q: How much of the energy transition can be driven at European level? In your book, you argue in favour of nationally binding targets and support schemes, but against the renationalisation of energy policy.

A: The physical reality is that in a Germany which is 95-100% powered by renewable electricity, 80% or more of those renewables will stand on German soil. Of course there are some cost reductions possible between Germany and its neighbours, but we should not suggest that Germany will import 80% of its power in future.

In the book I have tried to develop a new frontier – regional cooperation – to get out of fruitless discussion over national vs. European. This is above all an issue for electricity. Everybody knows that organising electricity in larger geographic areas is cheaper than doing it at national level. What I propose in my book – and what I will propose as rapporteur of the Governance Regulation [part of the Clean Energy Package] is to motivate governments to work together.

Q: Will you re-table the idea of nationally binding targets for renewables and energy efficiency?

A: I will at least seriously consider them. They have driven the successful renewables deployment of the last few years and all investors tell me that binding targets and stable support schemes are the best way to reduce capital costs.

There is a two-fold approach to ease the acceptance of binding national targets – opportunities for system cost reduction at regional level and opportunities for dynamism at local level.

Q: What do you see as the role of the EU ETS going forward? In your book you say it’s not achieved much but you’re not in favour of scrapping it either.

A: I think the EU ETS – at least as long as we have unanimity on energy taxation – is the only way to get some pricing of CO2. My best guess also after last week’s vote in the European Parliament, is that we should introduce a carbon floor price. This would provide a more stable outlook for the carbon price and revenues [from selling carbon allowances] for finance ministers, and it would help bring the electricity wholesale market back into the range of €40-60/MWh (up from <€30/MWh today).

I think it will be an EU ETS+carbon floor price+Emission Performance Standard (EPS) to prevent new coal being built in Eurooe. The 550gCO2/kWh [EPS] on the table [a ceiling in the Clean Energy Package for capacity markets] should stay on the table.

Q: Do you see any support for a carbon price floor? Apart from France and the UK, no member state appears to have taken up this cause.

A: The situation in Germany is still evolving. After the German election [this autumn] I’m pretty optimistic that Germany will sit down with France, the Benelux, Italy and the Scandinavians. From the end of 2017 we could get a large area of Europe under a carbon price floor, I would say.

Q: You talk about Brexit in the book and how it has already shaped key decisions in EU climate and energy policy (e.g. Hinkley Point C). How might it influence things going forward?

A: War is war. We risk 2-3 years where investments in new cables or certain offshore wind projects are stalled. But I think that after two rough years, there could be an energy agreement. The British are interested in a deal on energy because without Europe, British prices would be 2-3 times higher than on the continent. Of course if Europe brings lots of advantages to the UK, the UK would have to stick to certain EU internal energy market rules in return.

Q: What, ultimately, is driving the energy transition? How much is it really under the control of policymakers?

A: I think it was largely a policy-driven transition and it will remain a policy-driven transition. But we are in a much better position today because of the reduced costs for renewables and all the ICT/big data developments. I am relatively optimistic that we can speed up the energy transition with three big pushes: policy, technology and a bottom-up dynamism from citizens and cities.

Q: Do you think the Juncker Commisison believes in the energy transition?

A: I have mixed feelings. I think that they have started to understand that what the Barroso Commission put on the table in January 2014 – which was largely confirmed by heads of state and government in October 2014 – is too weak not only to address climate change but also to guarantee solid industrial development in Europe and to reconnect with citizens.

Q: If you had to pick one urgent action for Europe on energy and climate policy, what would it be?

A: I think it’s identifying what I would call “Renewables Projects of European Interest”, be it offshore wind in the Baltic or North Sea, the fast development of electric vehicle charging stations in Germany or France, or projects in Southeast Europe to reduce capital costs. What is important is creating visibility and showing that Europe has an added value.

This piece has been republished with permission from Energypost.eu. It was written by Sonja van Renessen.