This post summarizes the key points of a report “Advancing Climate-Compatible Infrastructure Through the G-20 – Opportunities for Progress Under the German Presidency” by the Center for American Progress and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung North America.

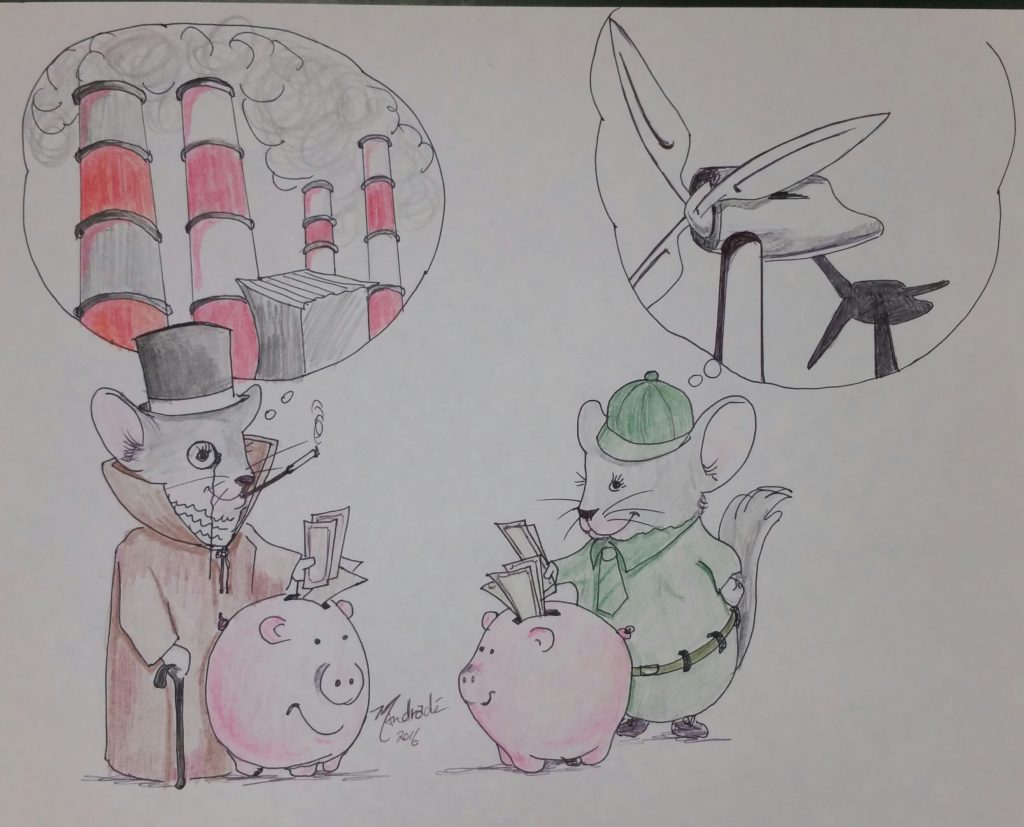

How to invest? In brown or green infrastructure? (Picture by Moses Andrade, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

To date, 17 countries of the G-20—which account for 67 percent of global greenhouse gas pollution—have officially joined the Paris Agreement, bringing it into effect far sooner than anyone expected. If these countries follow through with their commitments to reduce emissions, it will represent unprecedented progress in the global effort to curb climate change.

Unfortunately, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has proposed a number of policies that would have negative climate implications. In light of this, the G-20 summit in July 2017 provides an important opportunity for other major powers to resist backsliding and even to make some progress in meeting the global climate challenge.

The G-20 and its membership

The G-20 is a forum for global economic governance. It includes 20 of the world’s largest economies: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, the European Union, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

To its credit, the German government, which officially assumed the G-20 presidency this month, is already positioning itself well—and deliberately so—for such an effort. When German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced her three “pillar” objectives for the summit, she explicitly identified climate change as a priority. The pillars include fostering global economic stability; making the global economy viable for the future, including through implementation of the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; and establishing the G-20 as a “community of responsibility,” including by promoting a compact with Africa that would address infrastructure investment, among other topics.

If the G-20 focuses on making infrastructure low carbon and resilient—which would have widespread social benefits—it can make progress across all three pillars. Infrastructure projects that are vulnerable to the physical effects of climate change can cause profound economic damage, while high-carbon projects drive further climate change and economic risk. And given that G-20 countries account for more than 75 percent of greenhouse gas pollution and more than 85 percent of global gross domestic product, they have both the responsibility and the resources to promote low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Focusing on climate-compatible infrastructure would be a step forward for the G-20—although one that is rooted in its past and ongoing work. The forum has expanded its infrastructure initiatives in recent years, but the climate and infrastructure workstreams have been largely siloed, despite the fact that the majority of the infrastructure sectors in which the G-20 is promoting investment—energy, transport, and water—are inextricably linked with climate issues. By creating an integrated infrastructure and climate agenda, the G-20 could build on several existing strands of work and fight to preserve global climate progress. Here are five opportunities.

1. Identify and disclose transition risk

As investors, civil society, and governments increasingly turn away from greenhouse gas pollution, the value of assets will shift. High-carbon assets will decline in value or even become stranded: The fossil fuel industry, for example, could lose more than $30 trillion over 25 years. An abrupt reassessment of asset values, however, could have a destabilizing effect on the global economy.

The first step in mitigating this risk—called transition risk—is identifying it. It is in the economic self-interest of companies, investors, and nations to have a clear view of the financial risks and opportunities presented by climate change—particularly in the context of infrastructure projects, which can have decades-long life spans.

Currently, too few companies accurately and thoroughly report their exposure to climate risks. To counter this, the Financial Stability Board—an international body that promotes global financial resilience—created the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, which is currently developing disclosure guidelines that will be finalized in advance of the July 2017 summit.

With the guidelines in hand, the G-20 should turn to the task of promoting implementation. Going forward, G-20 members could adopt a leadership role by considering and publicly disclosing physical and transition risks in major federal projects in order to protect their national economies over the long term. They could also work to institute these practices among the development banks of which they are members.

2. Strengthen fossil fuel subsidy reform

In order to improve investment in climate-compatible infrastructure, countries will need to increase public expenditures and foster the market conditions that attract private finance. Fortunately, the G-20 countries committed in 2009 to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies—a step that drives progress on both of these fronts. Such subsidies divert public dollars away from infrastructure spending and tilt the investment playing field against renewable energy.

To help build momentum for fossil fuel subsidy reform, the G-20 began a peer review program in which countries can engage in an information-sharing exercise. The first of these peer reviews—completed by the United States and China—was publicly released during the 2016 summit.

Under the German presidency, the G-20 should build on this successful first review by improving and expanding participation in the process. For example, the United States and China could establish a precedent whereby countries that undergo a peer review participate subsequently as advisers. In addition, Germany could establish a channel for stakeholder input in the peer review process.

Importantly, the G-20 should also build on its 2009 commitment and establish the year 2025 as a deadline for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies.

3. Include Paris goals in growth strategies

The growth strategy of each G-20 country—which includes infrastructure plans—has been a crucial contribution to the collective effort to foster economic recovery and prosperity. Countries should include their Paris goals to reduce greenhouse gas pollution and build resilience to the effects of climate change in their growth strategies. This would give their climate commitments credibility and would allow countries to plan, in an integrated way, how to achieve a stable and low-carbon economy.

The Paris Agreement calls on countries not only to submit near-term climate goals but also to formulate national midcentury strategies to decarbonize their economies. Four G-20 countries—Germany, the United States, Canada, and Mexico—have already created their midterm strategies. All G-20 countries should create them by 2020 and include them in their plans for growth.

The G-20 could also implement peer reviews of national progress in adopting renewable energy technologies in the context of their midcentury strategies. This would be in keeping with the forum’s practice of implementing peer reviews when national progress is essential to reaching collective goals.

4. Expand access to climate-risk insurance

The world is already locked into a period of increased climate risk and damage due to the past 150 years of pollution that has accumulated in the atmosphere. This necessitates increased emphasis on enhancing climate resilience.

Recognizing this, the G-20 should promote climate resilience as part of its focus on infrastructure development. In addition, the G-20 should expand access to climate-risk insurance, which can help hedge against potential losses from extreme weather events, providing more security for investments. Climate-risk insurance can also assist with post-disaster recovery and create incentives for adaptation measures.

In 2015, the G-7 set a goal—through an initiative known as InsuResilience—of providing climate-related risk insurance to 400 million additional people in the most-vulnerable developing countries by 2020. Under the German presidency, the G-20 could adopt this same target. It could also address the obstacles to achieving it, such as stakeholders’ lack of familiarity with the innovative policies—for example, parametric risk insurance, regional risk pools, and microinsurance—that present opportunities to expand insurance to new populations.

To this end, the G-20 could support a platform for sharing insurance policy designs and best practices that would be open to all countries, subnational governments, regional organizations, and nongovernmental organizations.

5. Steer investments toward climate-compatible infrastructure

There are a variety of tools that the G-20 could promote in its infrastructure initiatives in order to mitigate transition risk and steer investment toward low-carbon options. For example, G-20 countries should consider the rising cost of carbon pollution in infrastructure investment decisions—a practice known as proxy carbon pricing. This evaluation tool—already well known in the private sector—is inspired by fiscal prudence: Factoring in a proxy price when assessing long-term projects can help countries and businesses determine whether they will remain financially viable in the global shift away from carbon pollution. In the future, G-20 countries and businesses should expand the use of proxy prices that are indexed to the damage to society caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

It is vital to prevent the progress on global climate action from slowing. Fortunately, this year’s G-20 under the German presidency can provide a near-term line of international defense—and it even has the potential to drive progress by integrating its infrastructure and climate agendas. Moreover, doing so would be true to the founding purpose of the G-20, which is to support global economic stability. This cannot be achieved without climate-compatible infrastructure and, more broadly, a swift transition to a low-carbon global economy.

The Authors:

Nancy Alexander is Director of the Economic Governance Program at Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung North America. For decades, she has headed up or worked with organizations to promote the accountability, participation, and transparency of global, regional and national governance bodies. This article has been reposted with permission from her Just Governance Blog, which monitors and critiques the performance of the G20.

Gwynne Taraska is the Associate Director of Energy Policy at the Center for American Progress. Pete Ogden is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Howard Marano is a Research Assistant at the Center for American Progress.

The Center for American Progress thanks the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung North America for its support of our energy programs and of this column. The Center for American Progress produces independent research and policy ideas driven by solutions that we believe will create a more equitable and just world.

The fact that agreement on a 2025 deadline for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies would count as a breakthrough shows how dismally slow is the transition from the shining commitments of the Paris Agreement to actual policy. Fossil fuel subsidies should have gone already. The debate should be about phasing in a carbon tax.

To agree on anything at all, Merkel will have to abandon the diplomats’ favoured rule of consensus. Take a vote and let Trump stew. For the next four years, the only attainable coalitions will be coalitions off the willing.