Concerns about the cost impact of Germany’s energy transition now include the grid fee. The German Network Agency has clamped down on profit margins for grid operators. Craig Morris weighs in on the debate over whether all these grid lines are needed.

Bavaria, which provides the most solar power in Germany, will be covered by Tennet (photo edited, CC0 1.0)

In January, grid operators sounded the alarm: stabilizing the grid cost more than 1 billion euros in 2015 (in German). The numbers given at the time were as follows for Tennet, the Dutch-owned grid firm spanning from the North Sea through central Germany and down into Bavaria:

- 225 million euros (up from 74 in 2014) for the ramping of power plants (re-dispatching);

- 152 million euros (up from 92) for the grid reserve; and

- 329 million euros (up from 128) for the curtailment of wind power.

Germany has four transmission grid operators, and Tennet alone accrued 70% of the total cost.

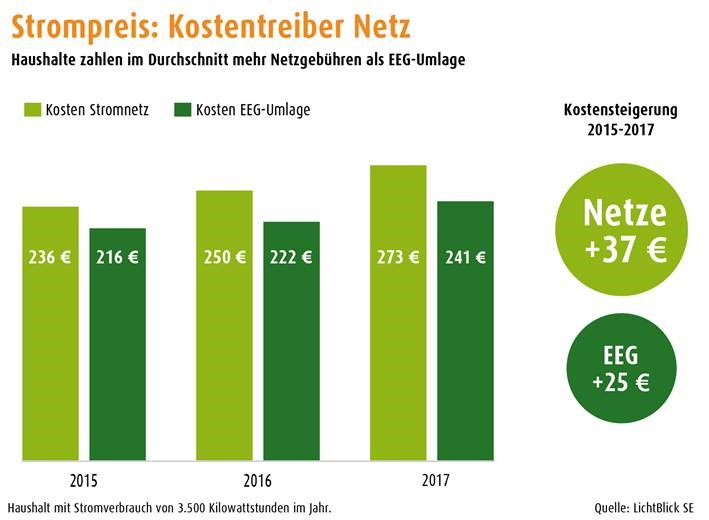

The chart below shows the cost impact of the grid fee (light green bars) compared to the renewable energy surcharge (dark green) over the current three years for a year in an average German household. In that timeframe, the grid fee has risen by 37 euros a year, compared to only 25 euros for the surcharge.

(Source: Lichtblick)

In September, the firm announced that it would increase the grid fee it charges by a whopping 80% starting in 2017 (in German). Tennet is responsible for some of the major grid projects underway now to improve connections between northern and southern Germany. The company also has to cover the areas with the most solar and wind: Bavaria for solar and northwest Germany for both onshore and offshore wind.

Still, not everyone is convinced that wind and solar are the sole reason for the congestion. Conventional power plants often have PPAs, meaning that they can continue to sell electricity to their contractual buyer even when prices on the power exchange dip very low. If all of the electricity in Germany were sold on the spot market, these plants would be forced to react more flexibly; the result might be less congestion. As things stand, re-dispatching has become a business model for conventional power plants. So the bottlenecks on the grid are brought about not by wind and solar alone, but the combination of this spiky renewable electricity with inflexible baseload.

In addition, the Phelix power exchange covers all of Germany and Austria, but the congestion is local. Hence, there are no price signals to incentivize, for instance, local demand shifting, power storage, or sector coupling. These options are, however, high on the agenda now.

Network Agency cuts margins

In light of the continuing low level of interest rates, Germany’s Network Agency, which oversees the German grid, has announced that profit margins will be reduced starting in 2018/2019. At present, the margin is 9.05% for new systems and 7.14% for old ones. Those levels are to be reduced to 6.91 and 5.12%, respectively. The announcement has caused widespread dismay in the sector; remember, grid operators sued to have the old rates put into double digits a few years ago and they lost the case.

Now, consulting firm Roland Berger says the reduced margins will hurt shareholder value, with small grid operators affected the most: they could lose “up to 35% of corporate value” (in German). German utility lobby group BDEW was also quick to point out that the calculation to determine the admissible profit margin effectively produces not 9.05%, but only 5.83% once other factors are accounted for. The press release also argues that higher rates are provided in “other European countries” (in German).

All of these statements are correct. They also do not tell the whole story. Roland Berger cleverly focuses on small firms because the public loves to hate big ones. And yes, producing corporate value is the goal when that value is artificially inflated with excessively high profit margins. The Greens agree with the BDEW that 9.05% is not the actual return, but their parliamentary inquiry puts the figure much higher at 14.4% (PDF in German) from 2006-2012. The Association of Energy Market Innovators (BNE), which represents new utilities, says an even lower profit margin of 5.04% would be enough (in German). Consultants from Prognos also find that all of these grid lines would not be needed if a distributed approach were pursued (in German).

And finally, other European countries may indeed offer higher returns, but capital is nowhere cheaper than in Germany. Capital has to pay to park in Germany; government bonds now offer a negative interest rate, as do long-term interest rates.

In the end, the only thing that can be said with certainty is that the way Germany is implementing its energy transition in the power sector is leading to the current cost level. It seems possible that current business models are blocking less-expensive approaches.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Tennet is the worst solution for the grid, I don’t know why they are running it.

Not only had they no means (money!) when competing for the contract to manage the grid – many off-shore connection were therefore delayed – they also show the worst performance when it come to quality.

One after the other cable is failing and Tennet still purchases from the same incompetent manufacturers. (Report in German)

http://www.iwr.de/news.php?id=32520

The non-producing wind parks – non-producing since not being connected – get money from the EEG-Umlage (the RE-surcharge) for the power theoretically delivered but de facto not being delivered. Due to Tennet, a Dutch state company who is very slow to accept the Energiewende.