It is often held that citizens get involved in energy coops in order to profit personally. That’s true, but it’s also overrated as a motive. Now, a new study puts the various reasons in context, and gives Craig Morris some hard data for what he says he already knew anecdotally from numerous such projects. The findings may surprise you—and the German government.

Visitors to the Westmill Solar Cooperative in the UK (Photo by MrRenewables, edited, CC BY-SA 3.0)

This spring, a friend told me about a new community energy project, where citizens were livid because the returns did not meet expectations. “People are calling up the developer to complain,” he said. “Doesn’t that show that the profit motive is the real driver?”

A new study by researchers from Germany’s Leuphana University (which does some excellent work in this field) asked that question—and the answer is no.

Join Craig Morris for a Massive Online Open Course on the Energiewende starting on Monday, October 24; see the link at the bottom of the article to sign up. The course is part of the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) educational program.

It turns out that personal profits are one of the least important motives—strengthening the community (including financially) is much bigger. This finding should not surprise us too much; citizens see community energy coops not only as a way of making a sound investment, but also of just being a good neighbor. These folks do other things like join the fire brigade, volunteer at their church or school, and chip in for local donation campaigns (see my recent coverage of the Prometheus study for more on that). Like those options, renewable energy coops are ways of getting to know your neighbors and making the community a better place—with a potential profit to boot, in the case of energy coops. But we should not be surprised to hear that being a good neighbor is still central to energy coops, which citizens view as another type of community commitment alongside volunteering.

The government’s targets also aren’t necessarily that important to people

What’s more, “energy security”—one of the federal government’s main objectives for the Energiewende—is at the bottom when it comes to personal engagement in an energy coop. The energy transition will indeed offset imports or uranium and fossil energy with domestic renewables, and that goal is important. It’s just not primarily why the average Joe or Jane gets involved.

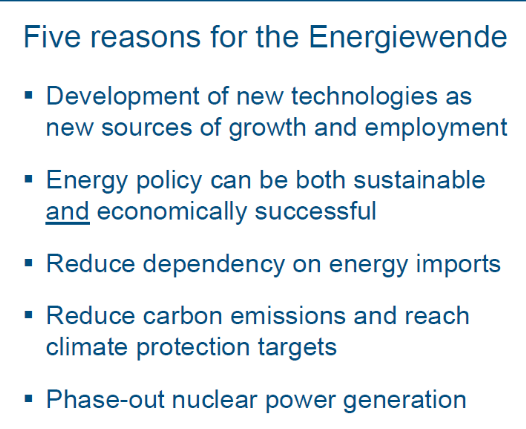

The main reasons behind the Energiewende for the German government are not the same as those for citizens to become involved in renewable energy cooperatives. Source: a presentation given by a representative of Germany’s Economics Ministry.

Another recent study shows (a bit inadvertently) how important it is to pose the question properly. This time, a “list of 14 goals put forward in political debates” was given to “50 policy experts” to create a ranking. Being a “member of a community” was thus not even on the agenda; it is never discussed by top politicians. (Here is the ranking, unfortunately behind a paywall.)

The paper does not ask citizens why they join energy coops. So, the actual discrepancy between the motives of top officials and those of the citizens (whose interests everyone allegedly acts in) only becomes apparent when we compare it to the other study under review here.

This finding holds a crucial insight for policymakers and project developers alike. We may enter talks with citizens with the government’s objectives as our main selling points for, say, a wind farm—only to find that people have other problems and interests.

Experts could first recognize the gap, and then start focusing more on the public’s concerns. The real driver behind local renewable energy projects seems to be, as several developers have told me over the years, saving the community first and the planet second. And to answer my friend above, yes, people in renewable energy cooperatives do get upset when their financial stakes do not pan out—because it hurts the whole community.

By the way, the video above is taken from the IASS’s new Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on the Energiewende, which starts on Monday, 24 October 2016. If you would like to learn more and sign up for the IASS’s six-week course (for free), just point your browser here.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He is co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s Energiewende, and is currently Senior Fellow at the IASS.

Hey Craig, nice article! By the way, the link to the IASS course doesn’t work. Best, Kat

And let’s note again that there are growing worries in Germany regarding local resistance to the further build-out of renewables, especially on-shore wind. An antidote is local participation; cooperatives are one possibility and there are others as well. It does look as if the German government is under-weighting this in its plans.

Fascinating findings.

Here in the UK the government has little truck with localism, but what they have leapt on is the wrong-headed idea that we are confronted by an “energy trilemma”. This says that we can have one, maybe two, but not all three of the goals of decarbonising, keeping the lights on, and getting bills down. Of course this is just a clever ruse to frame renewables as expensive.

Its notable how this differs from the much more optimistic, not to mention honest, ‘five reasons for the Energiewende’ of the German government you give above.

The Tory government in Britain has no interest in low prices for solar and onshore wind. These would reveal their strategy as fundamentally wrong-headed. Fortunately these are global industries and the costs will keep falling anyway. A few pioneering investors like Lightsource in renewable projects outside the incentive framework – and thus outside Whitehall control – may well turn into a flood.

I’m in a conversation with some Greek engineers – PV for local communities in Greece. In response to the post by Mr Ferguson – there is no “trilemma” –

Local PV – cheaper than the usual elec – check

Local PV – decarbonising – check

Local PV – keeps the lights on (with batts) – check

Of course if it is a blend of RES (e.g. wind & PV it becomes even easier).

In the UK, I’m looking at a P2G project and using on-shore wind – we believe that we can do the on-shore for 3 pence/kWh – no reason communities could not enjoy those sort of prices.