For decades, the Danes have been an inspiration to and role model for German and independent proponents. But the story of what they specifically get right is not well understood in the English-speaking world. Now, American journalist Justin Gerdes has filled that gap with a short Kindle book. Craig Morris says it’s a must-read.

Germany gets all the attention with its Energiewende, but who do the Germans pay attention to? Denmark.(Photo by CGP Grey, modified, CC BY 2.0)

Recently, I wrote about how Denmark’s new governing coalition is slamming the brakes on the country’s transition to 100% renewable energy in all sectors by 2050. The target itself has not yet been called into question, just the pace. Quite likely, abandoning the target of 100% renewables would be unpalatable in Denmark.

Consider that for a moment. There is a country on this planet without considerable hydropower or geothermal where revoking the target of 100% renewable energy in all sectors could get you voted out of office. The Danes are going to go 100% renewable largely with wind power, sector coupling, and efficiency.

The biggest oversight in Gerdes’ book is his downplaying of the anti-nuclear movement in Denmark, without which the Danish transition to renewables is unimaginable. Here, too, the Danes inspired the Germans, whose “Nuclear power? No thanks” emblem (right) was a literal translation of the Danish original (left). Source: Anna Lund, from 1975.

Germany gets all the attention, but who do the Germans pay attention to? Denmark. It arguably started in the early 90s, with a book called (in German) “Towards a new energy policy: What Germany can learn from Denmark.” The author was a young man named Holger Krawinkel, who later went on to become a top renewable energy proponent as a consumer advocate.

So what does Germany and Denmark have in common? Basically, you can just read Justin Gerdes book and assume that everything applies equally to Germany. The Danes got started in earnest a bit sooner (in the 1970s) and are more ambitious (Germany’s target is only 60% renewable energy by 2050), but both countries have a broad consensus for the transition: “The Danish Energy Agreement [of 2012] passed with comity unthinkable in today’s US Congress; 171 of 179 members of Parliament supported the plan.” Gerdes entitles one chapter “A climate of consensus.”

Danish companies are also often family-owned, with a commitment to their local community and workers. Gerdes focuses on some clean tech companies not as well-known outside Denmark as Lego and Maersk are: Danfoss, Haldor Topsøe, and Grundfos. Just as numerous German firms, they are global players in a niche market. What’s more, while American start-ups strive to go public or be taken over by a listed corporation (so the founders can cash out), Danish (and German) enterprises are often “owned wholly or in part by foundations controlled by defendants, ensuring long-term vision” as opposed to the focus on short-term profitability required at listed corporations. (One such example in Germany is Enercon, the country’s biggest wind turbine manufacturer; after the company’s founder retired, ownership was handed over to a foundation). Gerdes quotes the head of Haldor Topsøe, a Danish chemicals giant, explaining why these firms refuse to go public: “We cannot afford to have a short-term vision where you need to satisfy shareholders every quarter.” Later, he explains that Danish companies like Grundfos, “the world’s largest pump manufacturer,” remain “inextricably bound to the remote hometowns of their founders.” (Grundfos has its headquarters in Nordborg, population: 6,200).

Gerdes also explains how Denmark has always gotten the heat sector right, not just electricity. For instance, the district heat network in Copenhagen covers 98% of the city. And of course, the Danes get cycling right. A Danish urban planner tells Gerdes how he responds to doubters from abroad, who claimed that European policies won’t work because their home city is not Copenhagen or Amsterdam: “decades ago, neither were Copenhagen or Amsterdam.”

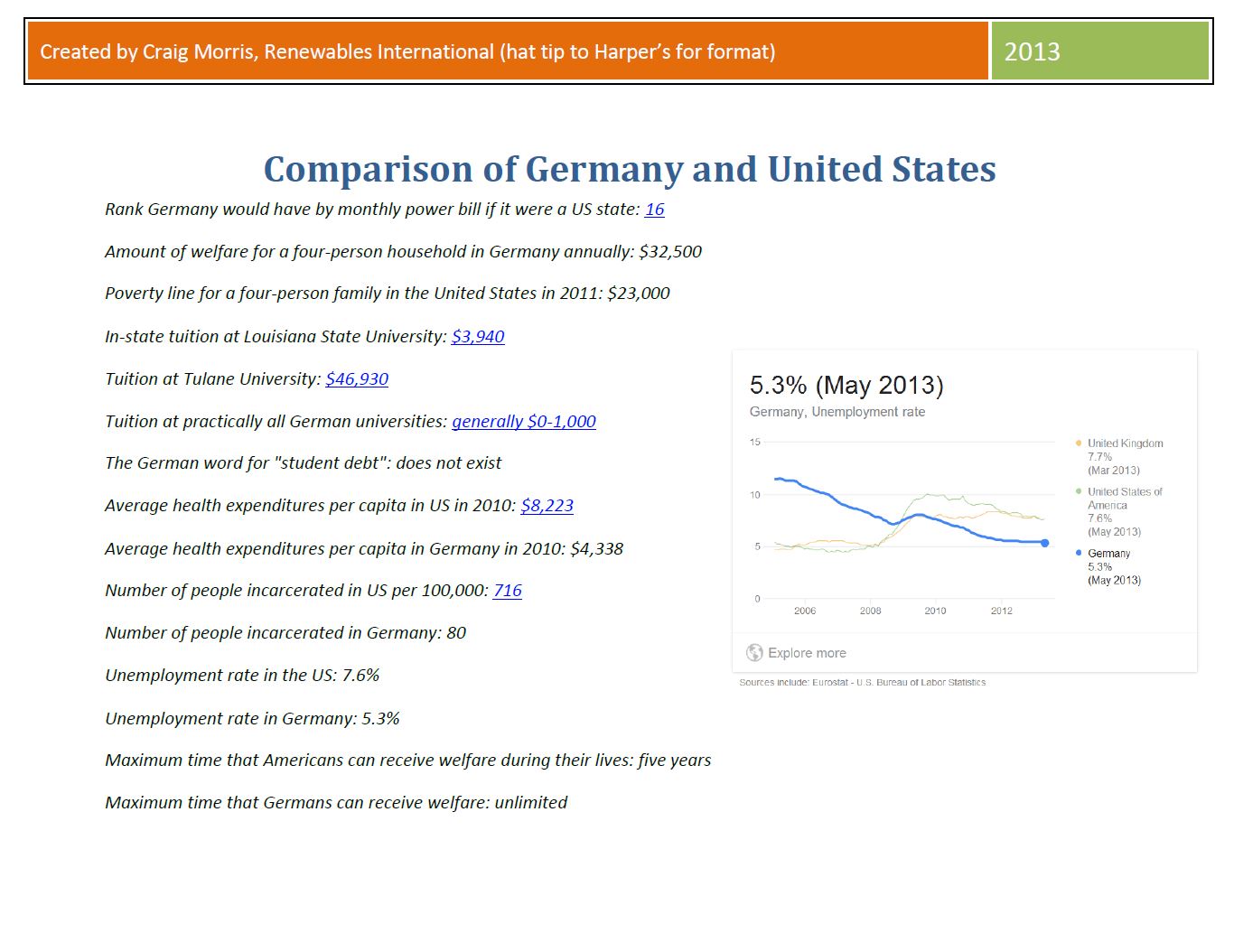

Nonetheless, at times I felt like Gerdes described his home country of the United States as much as he shed light on Denmark: “Danes don’t struggle with the ruinous medical expenses or crippling student loans that, in the United States, at least, too often trigger bankruptcies and derailed dreams.” In fact, the US is “special” in that comparison, not Denmark.

To my mind, Gerdes also downplays Denmark’s rejection of nuclear, which was very early and absolute: “In 1985” – the year before Chernobyl (!) – “Parliament rejected proposals to develop nuclear power,” Gerdes writes. Had he written more, he may have scared off many in his US audience who mistakenly believe that nuclear is a good complement for wind and solar power.

Thx, I can use that to show Germans not to speak of decarb or clean energy. For Anglos, that includes nuclear https://t.co/4BwSKLCAbN

— Craig Morris (@PPchef) June 1, 2016

But overall, Gerdes’ short book is a must-read for anyone interested in renewables and energy policy internationally. In the end, Gerdes even explains the pitfall of a government using soft power to push for renewables. Though he is speaking of Denmark here, the insight equally explains the international watchful eye on Germany: “To position oneself, or to be anointed, as a leader is to expose oneself to outside scrutiny.”

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.