In April, a renewable energy auction in the United Arab Emirates produced an astonishingly low price. At 2.99 cents per kilowatt-hour, solar power suddenly costs half as much as it did a year ago. It has thus practically reached the level experts hoped for 2030. Craig Morris explains.

A winning bid of a record-low 5.8 cents in Dubai drew international attention in late 2014. (Photo by Tim.Reckmann, modified, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Solar power is now cheaper than coal, cheaper than everything else – this, at least, is the main take away from all media reports on the new record-low bid for solar power in Dubai. Bloomberg New Energy Finance is among the most circumspect in reporting on the issue, with its Jenny Chase commenting, “Nobody knows how it’s meant to work.”

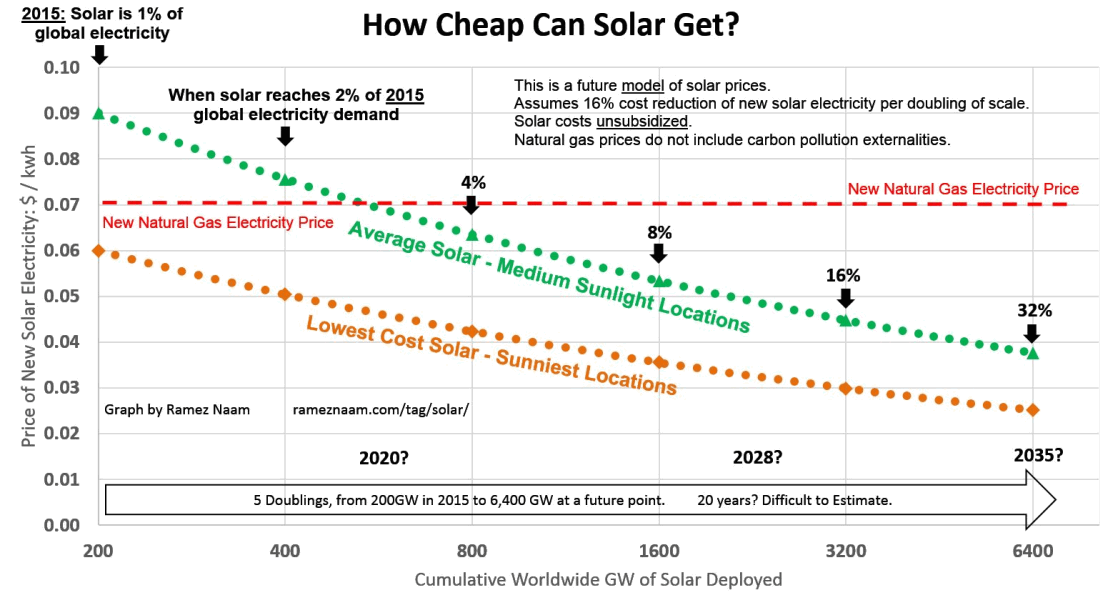

Solar power was not expected to hit 3 cents per kWh until 2030. Source: Ramez Naam

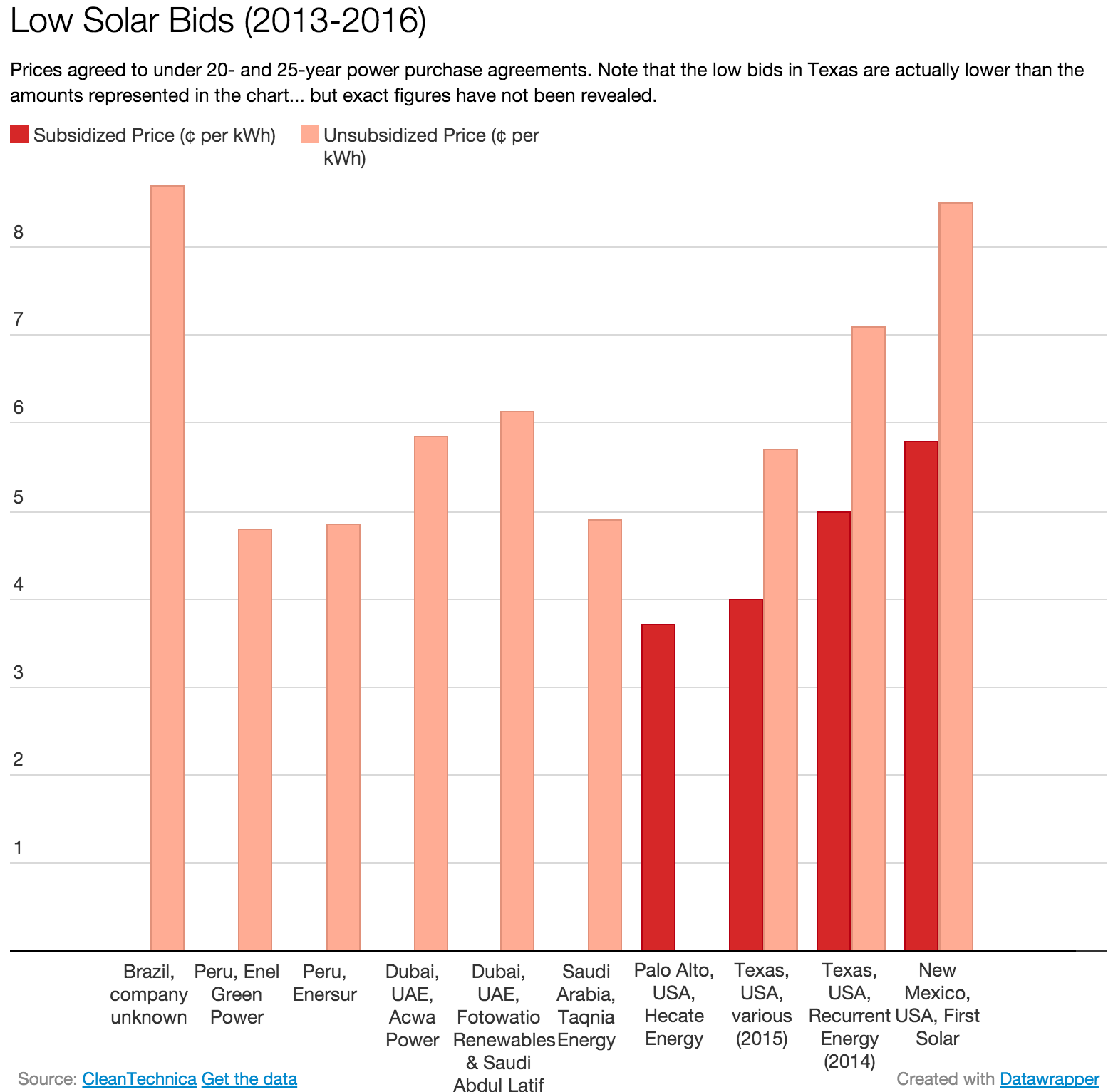

In late 2014, a winning bid of a record-low 5.8 cents in Dubai drew international attention. Since then, we have seen prices for solar power bids plummet even further to 4.8 cents in Peru and 3.5 cents in Mexico (the latter partly subsidized, however).

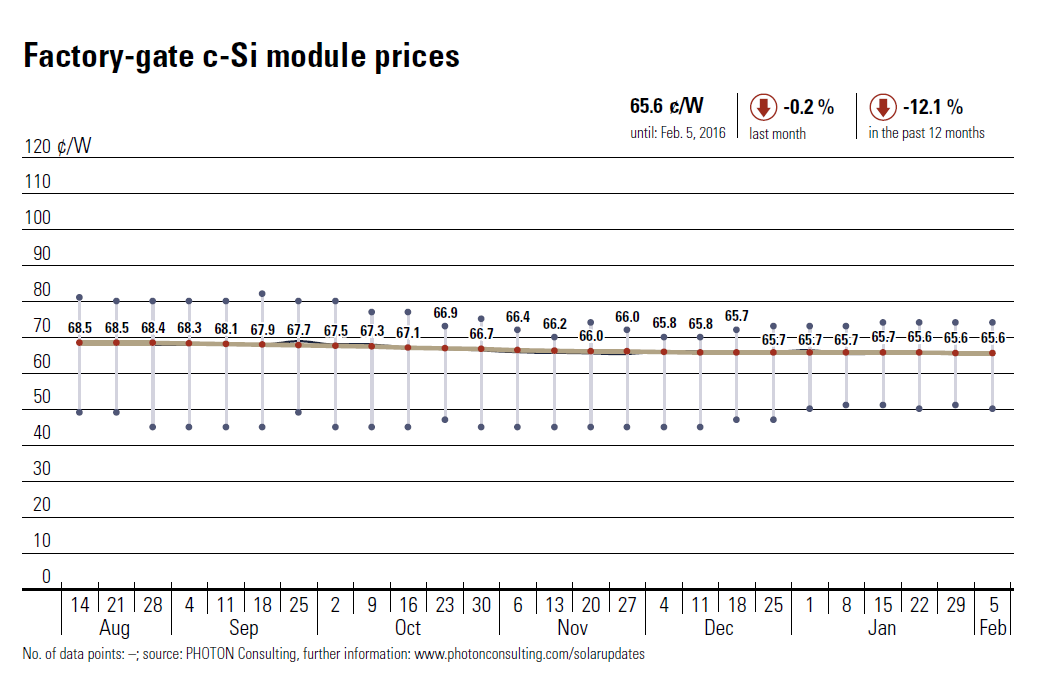

Nonetheless, market onlookers like Bloomberg’s Chase are increasingly skeptical because system prices have not been cut in half over the past year.

Prices for crystalline silicon solar panels (the type most frequently used) were down only around 12 percent over the past year. They make up nearly half the total cost of an array. Source: Photon

In this blog, we have written about how “soft costs” – permits, labor costs, grid connection requirements, and other red tape – have traditionally made solar more expensive in the US than in Germany; certainly, soft costs will be very low in Dubai. We do not yet know the details, which are still confidential, but I spoke with energy analyst Toby Couture of E3 Analytics, who specializes in the MENA region. He points out a number of things that are likely to make the low price hard to copy elsewhere.

First, the bid came from a consortium led by Masdar, essentially a company owned by the UAE. Couture says it is likely that Masdar felt it needed to win the bid politically in order to gain a firmer footing in its home market. Couture adds that the arrangement “is effectively more of a PPP” (public-private partnership), than a traditional, privately financed IPP (independent power project).

The price itself is probably also artificially low due to a host of factors:

- Low land prices (possibly free);

- Very good loan terms (including low interest rates and quite likely a long loan tenor);

- An indexed price (i.e. escalating over time);

- Very low taxes in the UAE; and

- Low-cost labor.

The first, fourth and fifth items cannot be replicated everywhere. The second is crucial because solar power has no fuel cost and negligible operating costs, so almost all of the expenses are incurred on day one. Moritz Borgman of Apricum, another expert on solar in the MENA region, put it quite well: “One can suspect that Masdar had access to long-term financing through the wealthy emirate of Abu Dhabi that no commercial banks, the primary source of capital for the other bidders, could match in cost.”

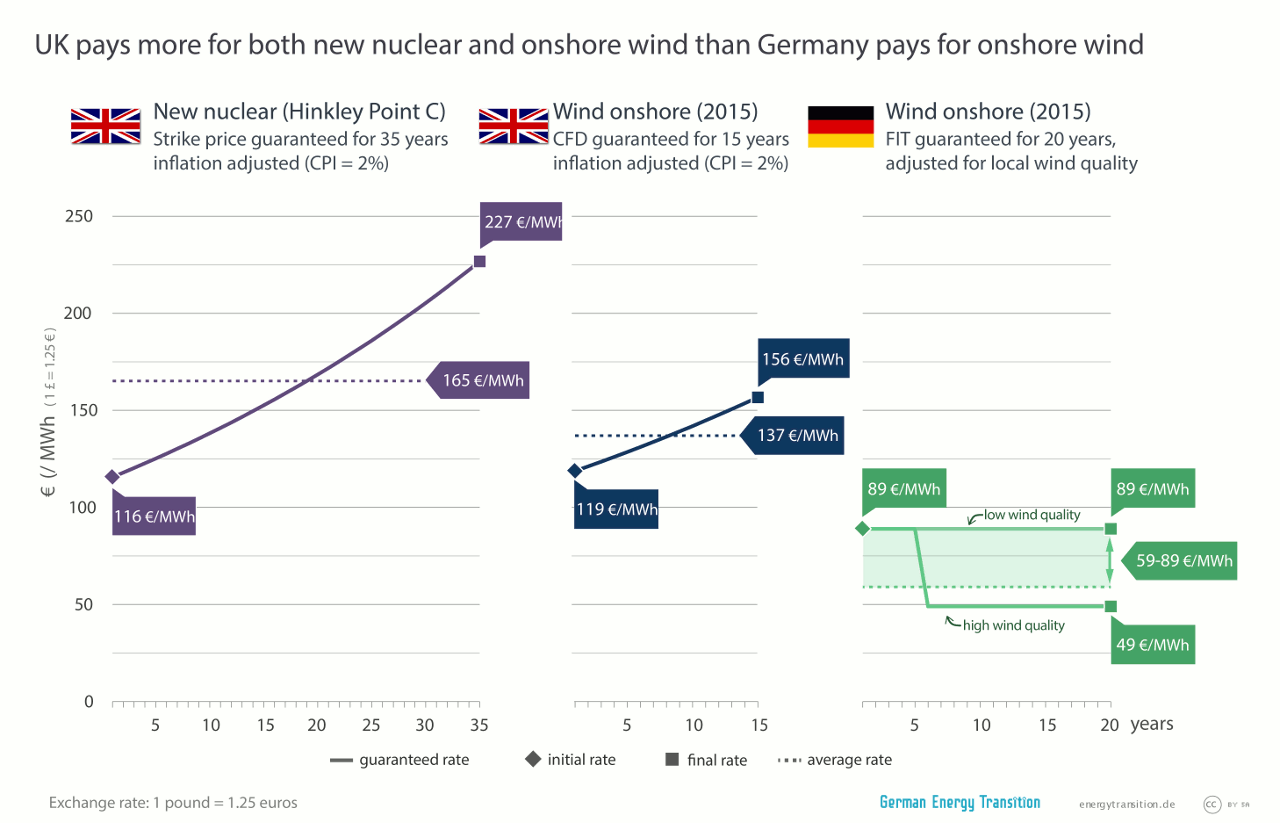

Finally, three cents is almost certainly just the initial price; it is probably pegged, for example, to the dollar in order to protect against significant currency devaluation. Another likely option is inflation adjustment or some other form of contract price escalation. In each case, the price would merely start at three cents – no one can say reliably where it would end up, however. In the chart below, we calculated what the inflation-adjusted strike price for new nuclear power in the UK (from the proposed Hinkley plant) would be over the guaranteed 35 years. At a mere two percent inflation, the price doubles over the guarantee’s timeframe of 35 years from 11.6 to 22.7 cents, producing a price of 16.5 cents midway after 17.5 years – roughly 50 percent higher than the starting price. As Couture says, the starting price is therefore almost irrelevant.

What we can say is that the record-low three-cent solar news is not an indication that auctions produce low prices. The projects that reached these low levels are in excellent locations and benefit from extraordinarily generous development and financing conditions. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether the project will even be built at these prices, as bidders frequently underbid in order to win contracts, as pointed out in a recent IRENA report on auctions (PDF).

What we can say is that the record-low three-cent solar news is not an indication that auctions produce low prices. The projects that reached these low levels are in excellent locations and benefit from extraordinarily generous development and financing conditions. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether the project will even be built at these prices, as bidders frequently underbid in order to win contracts, as pointed out in a recent IRENA report on auctions (PDF).

So solar at three cents is an exception. But clearly, it continues to get cheaper faster than experts expect.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

Excellent points, Craig. I recently posted on the same issue after running a pretty comprehensive financial model. It simply doesn’t work. See:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/does-3ckwh-solar-pv-tariff-still-make-economic-sense-oleg-feldgajer?trk=mp-author-card

The 2.99 cents per kwh is without subsidies. See the link below

That means all the comments above are not correct.

————————

The bids seen around the world this year without subsidies or incentives are even more stunning. Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) received a bid this year for 800 megawatts at a jaw-dropping “US 2.99 cents per kilowatt hour.” Two other bids were below US 4 cents/kWh, and the last two bids were both below 4.5 cents/kWh — again all of these bids were without subsidies!

http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2016/07/18/3797907/solar-energy-miracle-charts/

If in the near future all countries have fully renewable energy, supplying 90% of the world’s needs, what will happen to the middle east and Russia?

You are living in the past. Your whole reply indicates that. You don’t even read other people;s comments. The world has changed in 50 years, it’s changed in 5 years. Nuclear’s short of fuel ten years IAEA(Pub1104_scr.pdf ) for 2% world’s energy for 5…