30 years ago, Chernobyl made the public fear radioactivity, thereby setting back the progress of nuclear technology – most articles you read today about the accident probably say something along those lines. For Craig Morris, that reading is a major accomplishment for the nuclear sector. The real story looks much worse.

Reactor 4 under the “sarcophag” with the monument in front of it. (Photo by Tila Monto, modified, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On 26 April 1986, the Chernobyl reactor in Ukraine began melting down. Soviet officials did not report the event. Two days later, radiation meters in Sweden went off, however. Nuclear plants across Europe had such detectors for their own safety. The cloud from Chernobyl reached Sweden first and quickly engulfed the rest of Western Europe in the next few days.

Countries throughout Europe warned citizens of the risks. Italy banned the sale of fresh milk for two weeks for children and pregnant women along with the sale of fresh leafy vegetables. Austria temporarily banned the sale of fresh vegetables from Eastern Europe. The German government advised the public to feed powdered milk to babies and wash fresh vegetables thoroughly. It also reassured the public that “no such accident can happen in Germany” because that particular reactor type did not exist in the country.

Readings of elevated radioactivity levels taken across the continent were made public – outside France and the Soviet Union. At the time, Pierre Pellerin headed the SCPRI, an organization within France’s Health Ministry in charge of radiation issues. He publicly claimed that “the radioactive cloud did not pass over France.”

The radioactive cloud from Chernobyl over Europe a few days after the accident. The text reads, “Part of the cloud clearly passed over French territory between April 30 and May 5.” The emphasis in the text can only be understood against the backdrop of the history of lies. Source: Le Monde

Nonetheless, the nuclear cloud that allegedly stopped at the French border also set off alarms at nuclear facilities in Cadarache, Marcoule and La Hague. Pellerin instructed his staff to keep this information secret for their entire professional life. He remained at the helm of that organization from 1959 until 1996 – for 37 years.

Italy phased out nuclear immediately after Chernobyl. The Germans took a more deliberated stance, creating an Environmental Ministry and negotiating phaseout details until 2002. Chernobyl led the Germans to talk about shutting down existing reactors; no new ones had been proposed for years. The accident led to greater governmental accountability in Germany.

In contrast, the French (as researcher Karena Kalmbach points out) associate Chernobyl with state intransparency. As one French scientist who had been in Munich when the accident occurred put it, “Everyone was talking about it [in Germany]. In France, nothing!” Only in Alsace, the area of France with a German-speaking population, did local officials react – perhaps because they had access to media reports in German – by banning the sale of spinach.

Why did French officials lie?

In 1986, the French were committed to constructing 170 reactors and going 100 percent nuclear for energy (France reached 40 percent). French president François Mitterrand won the elections on an anti-nuclear platform in 1981, promising a moratorium on new construction. In 1978, he had contributed to a publication critical of nuclear entitled “Towards a different nuclear policy” (in French).

In office, Mitterrand did not slow down nuclear, however; he ensured its success in France. The elections apparently aged Mitterrand quickly, for he announced after entering office that “ecology is an illness that afflicts the young.”

Mitterrand decided to use nuclear towards recreating the grande nation. Obviously no longer a superpower, France was quickly falling behind the UK as well in the 1980s. The British had just discovered gas and oil in the North Sea. And unlike Germany, the French lacked cheap coal. Nuclear seemed the only option left. Once a leader of the anti-nuclear movement, Mitterrand was uniquely positioned to break opposition to nuclear – just as Angela Merkel, once a leader of the anti-phaseout camp, broke opposition to it in 2011.

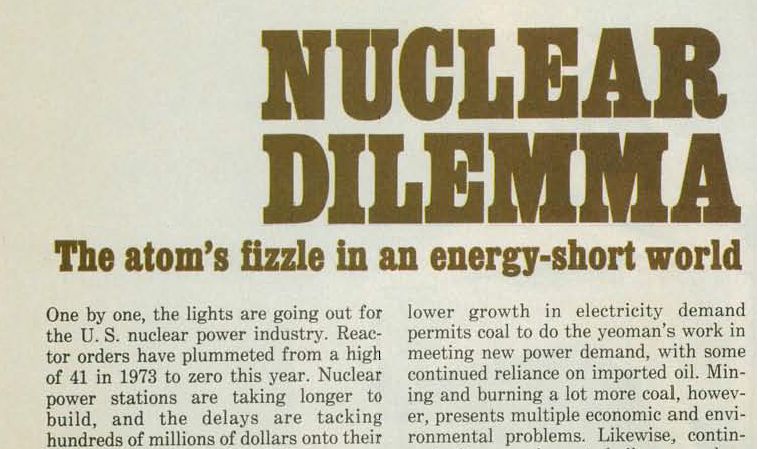

For new projects, nuclear got too expensive for bankers. By 1976, after years of subsidies, it was clear that nuclear power would not be competitive.

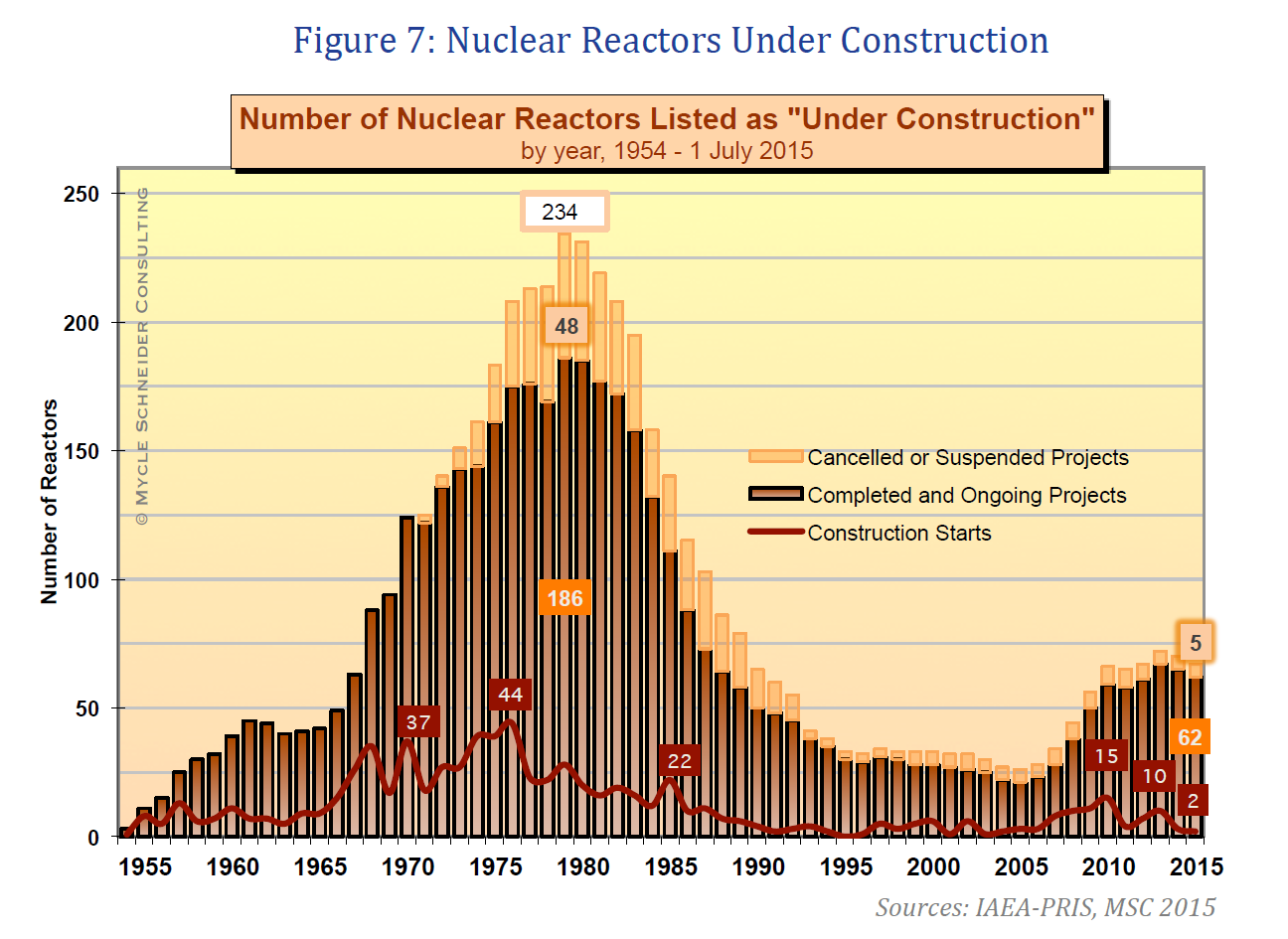

New nuclear plant construction peaked in 1976; cancellations, in 1978 – even before the accident at Three Mile Island (1979). France was the only Western European country to continue ordering a significant number of new reactors well into the 1980s (Germany started building its last one in 1982). Source: World Nuclear Report

An excerpt from BusinessWeek, 25 December 1978.

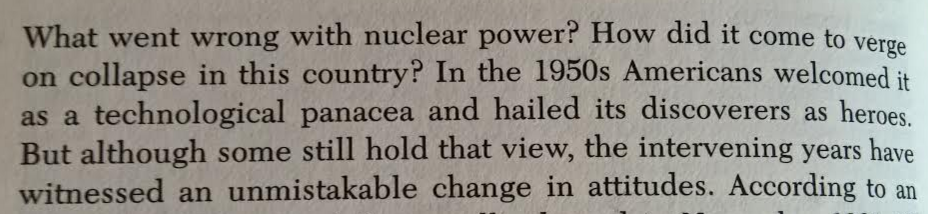

Excerpt from Mark Hertsgaard, Nuclear, Inc. (1983).

Chernobyl allowed the nuclear sector to claim that uninformed hippies blocked nuclear by spreading irrational fear. The claim not only overlooks Wall Street, but also supposes a level of influence that the environmental movement never had. Had Chernobyl not happened, we would all know that Wall Street, not fearful environmentalists, abandoned nuclear – in ‘76, not ‘86.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. Parts of this text are taken from the upcoming book entitled “Energy democracy: Germany’s Energiewende to renewables” (Palgrave).

its sad