A new study published by the Öko-Institut investigates Germany’s historical expenses for renewable electricity – and solar power in particular. In passing, the study highlights Germany’s contribution to the current low price of solar power worldwide. Craig Morris looks into the matter.

“The Germans were not really buying power — they were buying a price decline,” Hal Harvey, a US clean energy expert. (Photo by Rainer Lippert)

The study, which is only available in German but does contain an English executive summary, comes at a crucial time in the Energiewende debate. Back in 2013, industrial lobby groups that had just discovered their bleeding heart orchestrated an artificial debate over the rising renewables surcharge, which had not led to great public concern. Environmental Undersecretary Jochen Flasbarth recently called (in German) the debate “a hysterical discussion.”

The main focus of the new study is on how Germany’s renewable energy surcharge is not a good price tag for the Energiewende, which many people take it to be – but I’d like to talk about something else today: how the world benefits from German investments in solar from the past decade.

Increasingly, Germany’s commitment to wind and, in particular, solar power back in the years when these energy sources were more expensive is seen internationally as a contribution to Germany’s development policy. “The Germans were not really buying power — they were buying a price decline,” Hal Harvey, a US clean energy expert, told the New York Times back in 2014. This outcome was intentional; the Germans understood what they were doing all along: “We are responsible for this problem [of climate change] and should not shrug this responsibility by only thinking of ourselves,” former member of the German Parliament Hermann Scheer stated in 2000, when the Renewable Energy Act was first adopted as law. 14 years later, German energy analyst Markus Steigenberger of think tank Agora told the NYT, “we can afford this — we are a rich country. It’s a gift to the world,” he says.

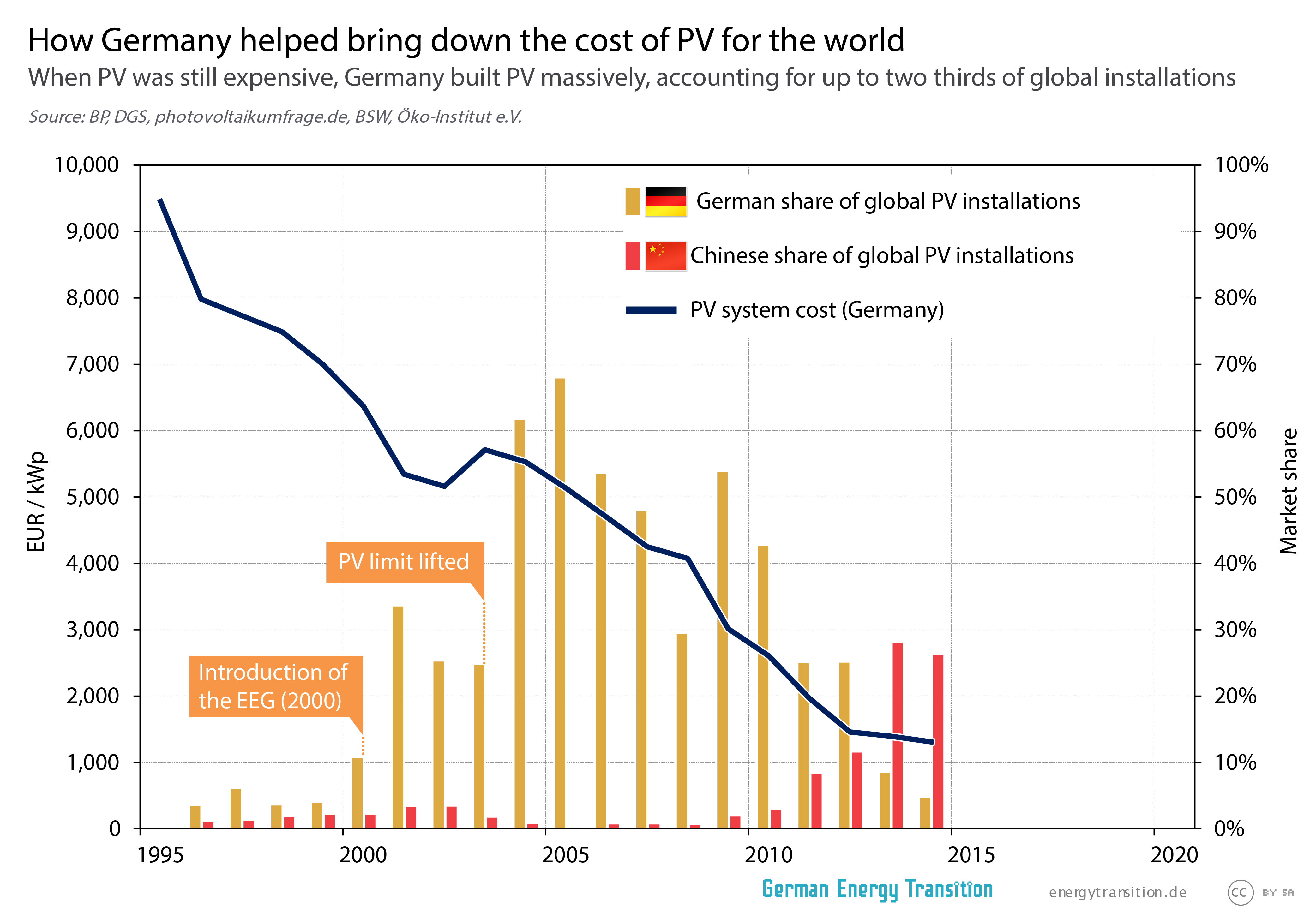

Now, the Öko-Institut has produced a chart highlighting the role that Germany played (below is our rendition of it in English):

Here, we see not the market share in terms of panels produced, but in terms of those installed. From 2008 until today, PV markets have come and gone (Spain, the Czech Republic, Italy, etc.), but the German market remained the buyer of last resort throughout those years. Germany was the only country that could be relied on to soak up all of the excess capacity built starting in around 2008.

The years from 2004 to 2007 were probably the most crucial. Germany made up more than half of the global market then. Relative to 2003, prices hardly moved, however. The reason was that German demand created a supply shortage. In particular, the solar sector had largely sourced its silicon from the IT industry up to then. But semiconductors are measured in square millimeters; solar panels, in square meters. Demand greatly outstripped supply in those years, sending prices up as manufacturers raced to set up new facilities for everything: solar silicon, solar cells, and solar panels.

During those years, Germany faced criticism for allegedly making solar more expensive for the world (see the slight uptick in 2003-2005). In 2006, the Economist wrote about the trend:

Governments that try to pick winners often choose losers. Subsidies distort investment: since the German government fixed the price for solar power at munificent levels, the country has been sucking in huge numbers of solar panels that could be put to better use in sunnier climes.

History has not been kind to this interpretation. Germany’s deployment of wind and solar when the technologies were expensive is now widely celebrated as the reason why significant production capacity has been set up worldwide, leading to plummeting prices for the benefit of developing countries in particular.

A comparison is revealing. In 2014, Germany spent around 12.5 billion euros on Official Development Aid (ODA). The amount spent on solar power annually is almost as high at 10 billion euros annually from its roughly 40 gigawatts of arrays (the most of any country in the world). According to the Öko-Institut study, the average cost of all this solar power is a whopping 30 cents per kilowatt-hour today; power from new arrays only costs 10 cents, but Germany paid closer to 50 cents for power from arrays installed before 2009.

Because this money does not go abroad, it cannot be considered ODA. And of course, the Germans themselves thought they were building up their own industry; in the same speech from 2000, former member of the German Parliament Herman Scheer stated: “we have to get the industry moving here.” Yet German feed-in tariffs never distinguished between domestic and imported solar products (PDF).

German PV demand helped set up the huge industry in Asia and North America, which now sells competitive PV to the Economist’s “sunnier climes,” as a growing number of experts agree. We await the Economist’s acknowledgment.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

The main problem: “The Germans themselves thought they were building up their own industry”. It takes too much courage to admit that this did not succeed al all and will not succeed.

As a result very expensive panels from the past hinder cheaper panels of today, and an awfull complaining by the solar sector about “lost jobs”

As Hermann Scheer also said “as you build new industries, there are always problems. There will be problems as we build the Renewable Economy. But we have to get started, there is no reason not to start.” Germany started and did the world a lot of good. Thank you Germany for leading.

Good article Craig. Thank you

[…] China and Germany have created a virtuous cycle by deploying solar and wind and bringing down the costs of the technology for everyone, Australia […]