Last year, Germany’s Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) published a survey of the BRICS countries, revealing their opinions on Germany’s energy transition. In April, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES) followed up with a study focusing on developing countries. Craig Morris reports.

Germany’s Energiewende has lead the way, now developing countries around the world are embarking on their own energy transitions. (Photo by Isofoton.es, CC BY 3.0)

Like the survey by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the one by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation is based largely on input from the countries surveyed. One main finding is that replacing current energy sources – such as coal and nuclear in the case of Germany – is not the only goal in many of these developing countries. Rather, “the majority of these countries also aim to reduce the acute energy deficit.” The question is here is more about how to meet rising energy demand affordably while allowing broader energy access to rural communities. Overall, with the exception of Brazil, the countries said Germany was leading the way of the energy transition and acknowledged that renewables are the energy source of the future.

Strangely, though the study speaks of “developing countries,” it not only includes Brazil, but also South Africa. Other interviewees came from Peru, India, Jordan, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Ecuador, and Bolivia.

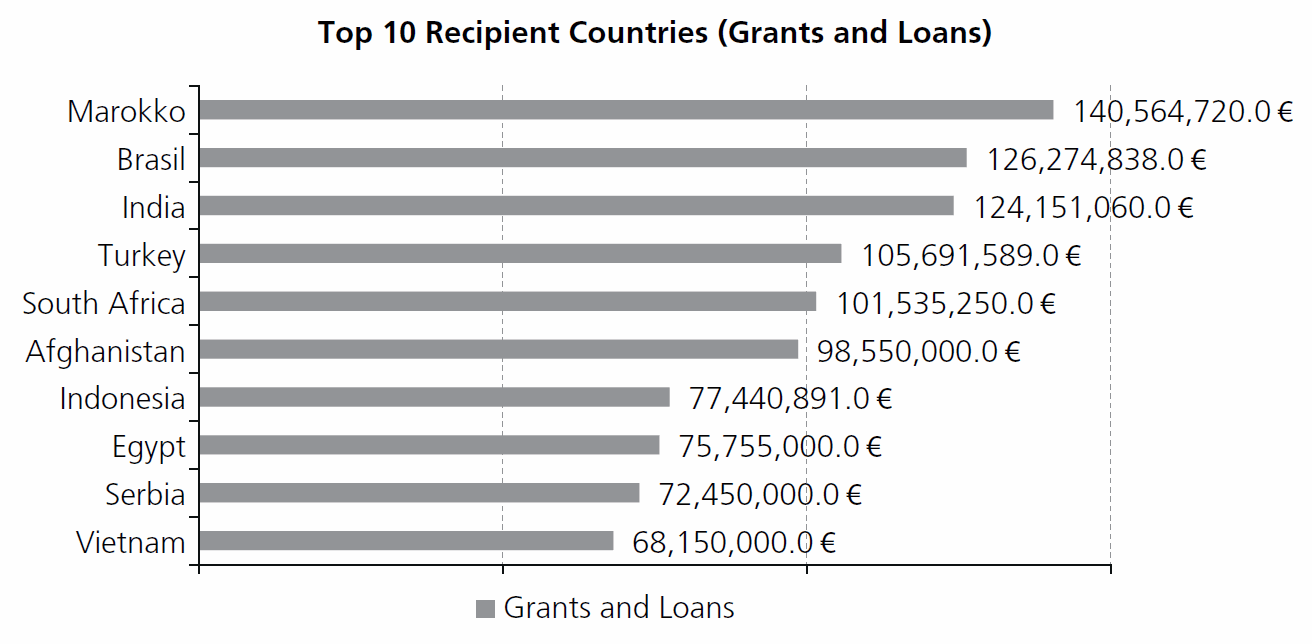

The top 10 recipients of German climate funding from 2008-2012. Roughly half of the study is devoted to an excellent overview of German climate funding. Source: FES

Towards affordability, developing countries realize that the technology costs that Germany faced no longer exist for them: “as many respondents emphasized, the boom in renewables in Germany has globally contributed to so massive a reduction in the cost of a kilowatt hour of electricity – generated by photovoltaics or wind energy – that cost parity with fossil fuels is already being approached.”

Furthermore, numerous developing countries subsidize (fossil) energy for the poor anyway. Getting rid of those subsidies would thus strengthen state budgets, but an affordable alternative would need to be found. At the same time, lower energy prices must not lead to higher consumption levels. One participant from South Africa put it well: “There are two types of consumers: the poor who need the access to a subsistence level of energy and the rich who need to become more energy efficient.”

The study shows how political will was considered crucial. Not surprisingly, the first of five factors that lead to a renewable future was “reliable and favorable” policies. But the private sector also needs to be involved, as it is in Germany. The Energiewende has brought about a number of startups that are now international players (Enercon, SMA, etc.). Similar business opportunities exist for firms in developing countries as well.

Furthermore, the involvement of the public has led to great public support for the Energiewende, and social acceptance will be needed everywhere. As one participant from India put it, “the exciting thing about the Energiewende is not how much renewable energy has (been) installed so far, but how the German government, businesses and civil society are thinking about the energy transition.” The interviewees said the top-down approach to energy decisions in developing countries could be an obstacle towards a transition to renewables – too much vested political interest lies with the conventional energy sources. However, broad societal input came about in Germany over decades and will not come overnight elsewhere, as the study rightly points out.

Finally, the participants praised Germany for its international development work. German development agency GIZ in particular was singled out for its helpful input on many local energy projects throughout the developing countries.

One finding did not surprise me: “the impression often arises that Germany is afraid of its own success and therefore does not communicate the energy transition internationally as a success story aggressively enough.” Over the past few years, this has certainly been the case, but I get the impression that things are changing. The recent Energy Transition Dialog event held in Berlin is one example of how the German government is trying to engage with other countries proactively and put its best face forward. This study is another example.

Its recommendations include sustainable international climate funding that is also integrated in an ambitious overall strategy. Pilot projects are to be conducted to demonstrate what energy transitions look like on a small scale, and the study calls on Germany to promote civil society dialogue along with scientific exchange in joint research. Furthermore, Germany’s KfW banking group should “refrain from allocating any new credit in the fossil-nuclear field.” And the first of the 10 recommendations at the end of the study really caught my eye: Germany has to communicate the benefits of the energy transition better.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

As you have rightly pointed out “too much vested political interest lies with the conventional energy sources”. I believe that is the reason for lack of political will to change to renewables, as many of the top politicians and businesses that fund election campaigns are engaged in the business of oil and petroleum or are owners of big coal mines especially here in India. To engage civil society at a large scale a greater awareness of the benefits of renewables as well as the demerits of conventional resources needs to be developed through non-profit means thereby encouraging a bottom-up approach to the transition.