Russia has submitted its climate goals to the UN. A close analysis reveals the shortcomings of the contribution, especially in regards to the role of forestry, as Sophie Yeo and Dr. Simon Evans explain.

As confusing as a birch forest – the Russian INDC. (Photo by Brian Jeffery Beggerly, CC BY 2.0)

This article was first published at The Carbon Brief under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

Russia submitted a pledge to limit its emissions to the UN on 31 March, simultaneously surprising and confusing many in the world of climate change.

Few had expected Vladimir Putin’s government to meet the UN’s loose 31 March deadline for “intended nationally determined contributions” – the series of national pledges that will, in part, form the basis of an international climate change agreement in Paris later this year.

Delivering its pledge just hours after the US, the Russian Federation left many baffled with its vaguely worded targets.

“Limiting anthropogenic greenhouse gases in Russia to 70-75% of 1990 levels by the year 2030 might be a long term indicator,” the unofficial translation of the submission says – in other words, a 25-30% reduction on 1990 levels.

But there are caveats. Unlike other countries that have pledged, Russia says its final decision is contingent upon the outcome of the UN climate negotiations, along with the INDCs of other major emitters.

It also says that its target include accounting as generously as possible for carbon dioxide absorbed by its vast boreal forests.

Furthermore, it points to Russia’s legally binding 2020 target, committing the country to limiting its emissions to 25-30% below 1990 levels – exactly the same limitation pledged in its new 2030 target.

Carbon Brief unravels some of the knots of Russian climate change policy.

Target but no peak

Russia’s emissions have followed a very different trajectory to most other developed countries.

Following the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of its carbon intensive industries, Russia’s emissions more than halved over the 1990s. They have been rising again since 2003 and its 2020 and 2030 targets allow for this rise to continue. The country is currently responsible for 5% of global emissions.

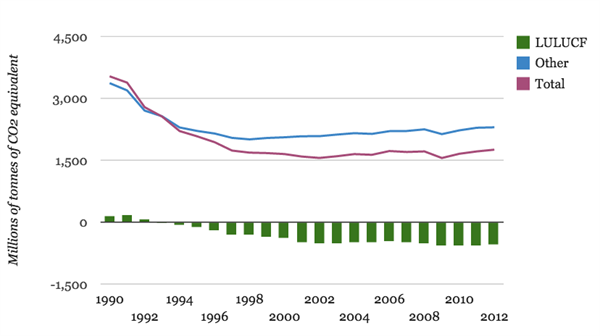

After the Soviet Union fell, Russia’s emissions declined as industry collapsed, while forests grew over abandoned farmland. Chart by Carbon Brief based on UNFCCC data

Russia’s 2020 target places a limit on this growth, capping emissions at 2,650 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, compared to 1,755 million tonnes in 2012.

This does not, however, mean that Russia intends to peak its emissions at this stage. In fact, in a statement delivered to the UN in September 2014 by Alexander Bedritskiy, Russia’s special representative on climate change, the country suggested that it did not intend to even stabilise its emissions for another decade after this. He said:

“Russia is expected to stabilise its energy consumption, and even lowering it, after 2030.”

The newly delivered INDC confirms this by essentially saying that Russia’s emissions in 2030 will be at the same level as they were in 2020.

This leaves a decade of mystery. The two targets suggest that Russia’s emissions will continue to rise after 2020, peak at some stage, and then decline until they hit 2020 levels once again.

But Russia has not yet indicated when such a peak might occur, nor has it set a total cap on emissions. This means we know what Russia’s emissions will be in 2020 and 2030, but there is no way of knowing how much carbon dioxide they will emit in between.

Since it is the cumulative volume of carbon dioxide emitted that determines how much the planet warms, this makes it difficult to assess how far Russia’s contribution will go to meeting the 2C limit set by governments.

Furthermore, Russia’s INDC does not significantly increase current ambition. According to Climate Action Tracker, existing policies would already be enough to push Russia beyond the highest end of its 2030 target.

Forestry

Russia’s 2030 climate pledge is further complicated by its inclusion of forestry.

Around half of Russia is covered in forest. This absorbs a lot of carbon dioxide, removing around 500 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year since 2000.

In 2012, Russian emissions were 18% higher when including land use. Chart by Carbon Brief using UNFCCC data

Russia says its 2030 pledge will include the highest possible estimate of carbon dioxide absorbed by forests when they come to count its national emissions. This means that, by continuing to manage its forests, Russia knows it will automatically reduce its carbon emissions by 500 million tonnes each year before even thinking about energy efficiency and renewables.

Seen in another way, this is 500 million tonnes of additional carbon dioxide that Russia’s energy and industrial sectors can emit every year before exceeding its target – equivalent to 15% of their combined emissions.

While the 2030 target is explicit that carbon dioxide absorbed by forests will count towards its overall emissions reductions, it is unclear whether they are permitted in its 2020 target. Russia’s 2010 Copenhagen Accord pledge to the UN said that it would allow for “appropriate accounting” of the forest sector.

Olga Dobrovidova, a journalist and fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, tells Carbon Brief:

“The language on forestry for both targets is deliberately obscure.”

If it does turn out that Russia uses its forests to meet its targets more in 2030 than it does in 2020, then its INDC for the Paris climate deal represents an overall weakening of ambition.

Alexey Kokorin, head of climate and energy at WWF Russia, tells Carbon Brief:

“The accounting of sinks is a big and complex issue that needs to be clarified in detail as soon as possible.”

Rising emissions

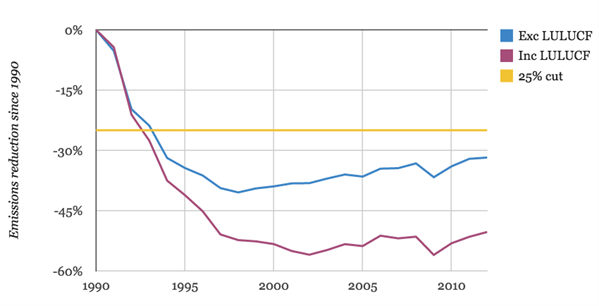

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia’s emissions fell to 56% below 1990 levels, including forests. They started rising gradually again in 2002 and by 2012 had reached 50% below 1990 levels. Excluding land use, they were 32% below 1990 levels.

This means that Russia can significantly increase its emissions over the coming 15 years and still hit the 2030 target set out in its INDC.

Even if Russia is to hit the more stringent 30% end of its target, this means that the country can grow its emissions by 41% between 2012 and 2030. Excluding its forests would have shrunk this to a growth of just 3%. This contrasts with most other developed countries, including the US, where emissions are moving in a downwards direction.

Environmental groups in Russia were unimpressed with their country’s intended contribution to the UN Paris deal.

Vladimir Chuprov, head of energy at Greenpeace Russia, tells Carbon Brief that Russia could reduce its emissions much further if officials implemented ambitious politicies to modernise Russia’s energy sector and industry. He says:

“For example, the energy efficiency potential in Russia alone is [equivalent to more than a 40% reduction in projected emissions]… But the state policies on efficiency and renewables are ineffective and must be strengthened to spur this transformation.”

Russia’s INDC does not commit it to reducing its emissions, nor does it set a definite peak. Its inclusion of forestry means that a significant burden is removed from the energy sector as the country attempts to stem its rising emissions by 2030.

Russia’s struggling economy, expected to shrink by 3% this year, means that emissions are likely to decrease this year, adding further slack to its emissions pledge.

The Russian government stops short of labelling its INDC a target, referring instead to its intended reductions as a “long-term indicator” – and even this is not set in stone. It emphasises that a “final decision” will depend on the actions of other countries.

Sophie Yeo covers climate and energy policy. She holds a masters in journalism from Cardiff University and studied English literature at Oxford University. She previously spent two years at RTCC, writing about the UN climate negotiations and international policy.

Dr Simon Evans is The Carbon Brief’s Policy Editor, covering climate and energy policy. He holds a PhD in biochemistry from Bristol University and previously studied chemistry at Oxford University. He worked for environment journal The ENDS Report for six years, covering topics including climate science and air pollution.