In December, American citizens petitioned the European Commission to “stop cutting our forests.” It turns out that Germany plays only a marginal role. Craig Morris investigates.

The United States exported more than 3.2 million short tons of wood pellets in 2013, mainly to Europe. (Photo by Kaibab National Forest, CC BY-SA 2.0)

On 11 December 2014, BirdLife International published a petition to the European Commission with the support of “over 50,000 US citizens”. The bone of contention is the cofiring of wood pellets in coal plants.

As someone born in Louisiana and raised mostly in Mississippi, I have expressed my skepticism at Americans pointing the finger elsewhere. Why should Americans appeal to Europeans rather than to their own government? Why can’t they simply ban biomass exports?

In reality, stopping exports will not solve the problem. North America seems poised to begin rolling out the cofiring of biomass itself as soon as this option becomes economically enticing. The first projects are already up and running. Ontario, for instance, just opened a new power plant that runs on “advanced biomass,” which – as we later learn in the press release – is wood pellets. Another facility fired with wood pellets opened last year in the Canadian province with the capacity of a mid-size coal plant at 350 MW.

Environmentalists in North America and Europe oppose such practices, and they now call on the European Union to ban imports of wood pellets. I support them in this goal but would also reiterate my recommendation that Americans first try to stop their own government from suing the EU if it does so. The debate over imports of shale oil continues, for instance; in December, the EU took another look at restricting imports of this “dirty oil” from Canada, but the Canadians will challenge the imposition of environmental rules against free trade. Why would Canada and the US respond any differently if the EU clamped down on imports of wood pellets from North America?

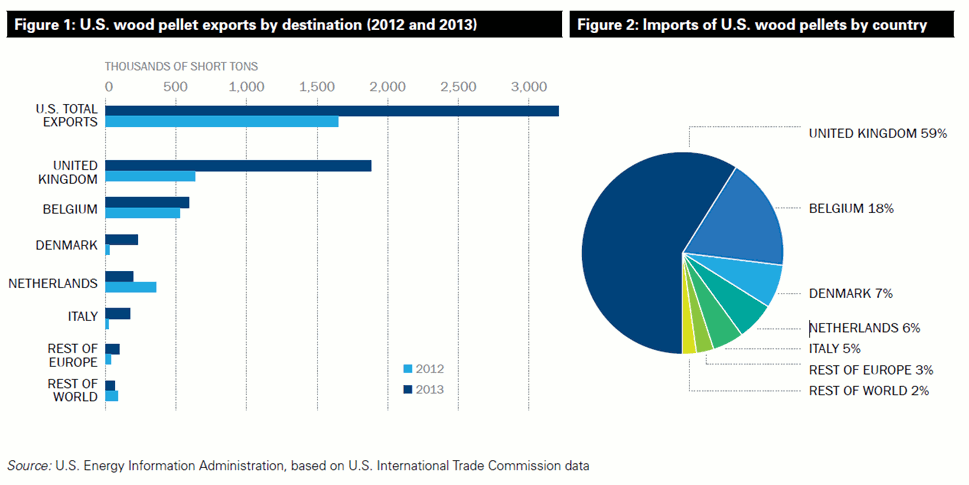

But today, I would like to point out something else in the data – Germany is not the problem. A paper (PDF) published in August by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) contains the following charts.

As you can see, Germany is subsumed under “rest of Europe” behind the UK, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Italy – meaning that the Germans can at most be in sixth place. They also cannot make up more than three percent of total exports from the US. Yet, Germany is a major consumer of pellets, as the next chart shows:

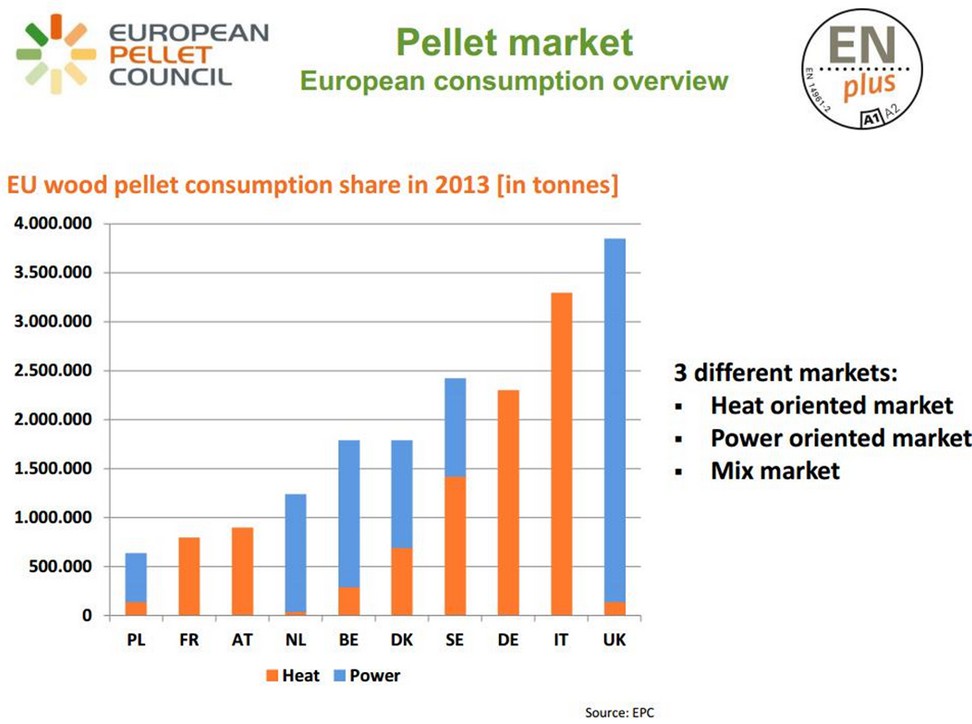

As you can see, Germany is subsumed under “rest of Europe” behind the UK, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Italy – meaning that the Germans can at most be in sixth place. They also cannot make up more than three percent of total exports from the US. Yet, Germany is a major consumer of pellets, as the next chart shows:

But notice the distinction – Germany (like Italy) consumes pellets exclusively for heat. The UK and Belgium, which collectively make up 77 percent of US exports of wood pellets according to the NRDC chart above, largely use them to generate electricity. This process is called “co-firing”; a small percentage of biomass is burned along with coal in coal plants. Because the waste heat from large coal plants is generally not used for any purpose, the efficiency of such plants is quite low. It is a bad idea to use biomass in such a wasteful manner, as our colleague Michał Olszewski recently explained in reference to the Polish situation.

But notice the distinction – Germany (like Italy) consumes pellets exclusively for heat. The UK and Belgium, which collectively make up 77 percent of US exports of wood pellets according to the NRDC chart above, largely use them to generate electricity. This process is called “co-firing”; a small percentage of biomass is burned along with coal in coal plants. Because the waste heat from large coal plants is generally not used for any purpose, the efficiency of such plants is quite low. It is a bad idea to use biomass in such a wasteful manner, as our colleague Michał Olszewski recently explained in reference to the Polish situation.

The Drax plant covers seven percent of the UK’s power supply. The firm itself speaks of “sustainable biomass,” by which it apparently partly means imports from the US. Numerous smaller cogeneration units would be twice as efficient, but the firm focuses on 40 percent efficiency gains from the very low level of the old coal plant before it was revamped. (Note that the technology was provided by Germany’s Siemens – did I mention the company is not always helpful in the Energiewende?)

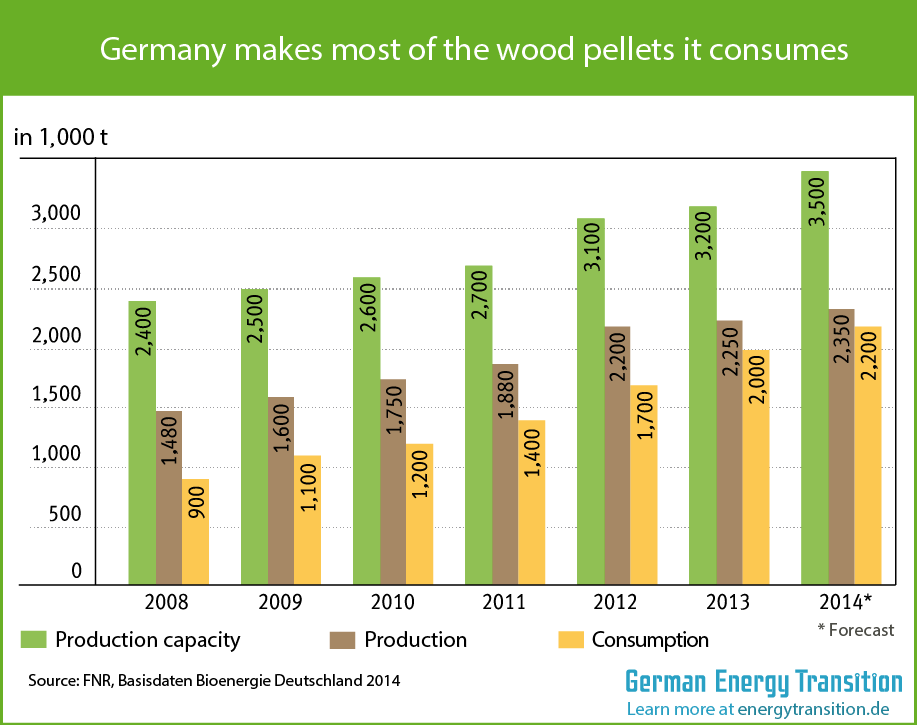

Germany consumes a lot of pellets, but they are all in smaller, more efficient heat plants. Furthermore, the country is a net exporter of wood pellets, as the chart below shows.

This is not to say that Germany has reached a level of sustainability for its biomass consumption. The Germans still import a lot of wood from around the world, much of which has not been certified as sustainable forestry. However, a lot of that timber is not consumed for energy purposes, but used to make furniture, build buildings, etc.

This is not to say that Germany has reached a level of sustainability for its biomass consumption. The Germans still import a lot of wood from around the world, much of which has not been certified as sustainable forestry. However, a lot of that timber is not consumed for energy purposes, but used to make furniture, build buildings, etc.

Clearly, the international trade of biomass needs to be closely monitored. But we need to realize that only a small group of European countries are actually cofiring a lot of timber from the US, and Germany is not one of them. In fact, stop the practice of cofiring in the UK and Belgium, and you have fixed three quarters of the problem in one fell swoop – this is not really a Europe-wide issue. Furthermore, Americans can appeal to the EU all they want, but as long as companies in the US are willing to ravage natural resources for profit, the problem will not be solved.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International. (Kudos to Arne Jungjohann and Thomas Gerke for helping with the research.)

Craig,

I think you need to defend your choice of words here. “Furthermore, Americans can appeal to the EU all they want, but as long as companies in the US are willing to ravage natural resources for profit, the problem will not be solved.”

Ravage is an emotional word and you know it. I think you also know that the facts don’t support the level of emotion the word carries. Any inquiry into growth and rate of take rates in the United States makes it clear that forests in the United States are not being “ravaged”. Finally, ravaging forests doesn’t make economic sense. Landowners keep their acres in forests so long as there are waiting markets for their fiber.

Interestingly enough, deforestation is happening in my home state of Minnesota. Why? Because the acres, as forest, don’t offer the same economic return to the landowner that the new use did. What’s the new use? Growing potatoes.

Tim

Most of the UK’s consumption of pellets is now going into dedicated biomass power plants, including at Drax, rather than co-firing in coal power stations.

[…] Nutzen für die Verbraucher von Holzpellets. Was diese NGOs vorschlagen, nämlich, in der Praxis, eine Ende von US-Importe von Pellets, ist in der Protektionismus. Während des G7-Gipfels war für die führenden Nationen […]