Over the past decade, German power firms made considerable investments in new conventional capacity. At the same time, German SMEs, energy cooperatives, and ordinary citizens made considerable investments in renewable generation capacity. The result is excess capacity. Craig Morris takes a look at some of the country’s energy experts who did not see this outcome coming.

The lights at the nuclear power station Grafenrheinfeld and other conventional power plants in Germany might go out faster than planned. One of the reasons: excess capacity. (Photo by MarcelG, CC BY-SA 2.0)

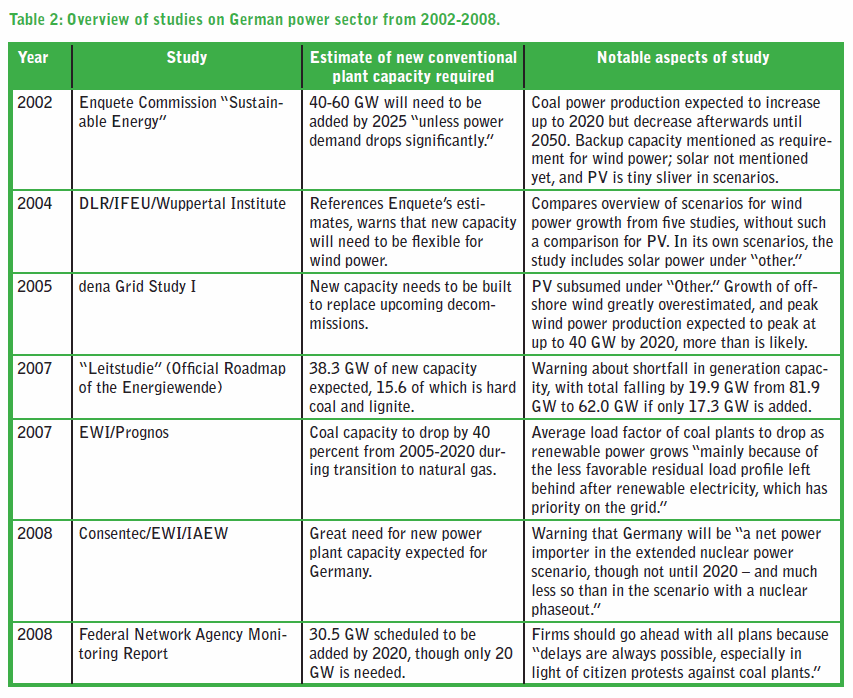

In our recent study entitled German Coal Conundrum, my colleague Arne Jungjohann and I show how Germany and the EU incentivized new power plant construction – including coal power – in the 2000s. We also reviewed some of the main studies from that decade to see what advice they would have heeded. Here’s the overview chart:

Clearly, business leaders were reading about the need for considerable new builds and the risk of Germany becoming dependent on power imports. Instead, we got record power exports in 2012 and 2013, and German wholesale prices are now consistently lower than those in neighboring countries. These experts underestimated the growth of renewables, especially the boom in solar.

This month, German journalist Dagmar Dehmer focused on Stephan Kohler’s recommendations as head of the German Energy Agency (dena). The table above mentions dena’s Grid Study from 2005, but Dehmer focuses on Kohler’s warnings about “power shortfall” from 2008. At the time, she quoted two independent energy experts who disputed Kohler’s concerns and argued that power firms may have been building so many new plants in order to get carbon emission certificates allocated for free.

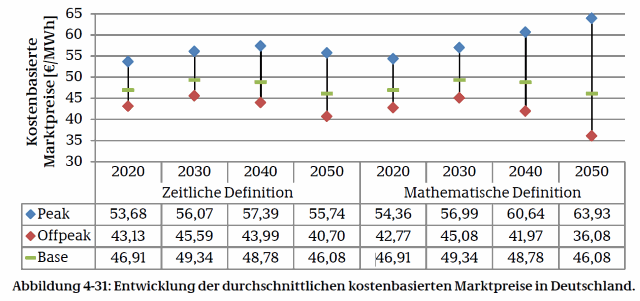

As recently as August 2012, dena produced completely inaccurate estimates of future peak and base power prices. By 2020, base power was to cost 46.91 euros per megawatt-hour, equivalent to 4.69 cents per kilowatt-hour. In reality, wholesale prices are falling, and the average base price in May was around three cents per kilowatt-hour, a third lower than dena forecast less than two years ago. Power prices futures up to the end of this decade are also down. Source: dena.

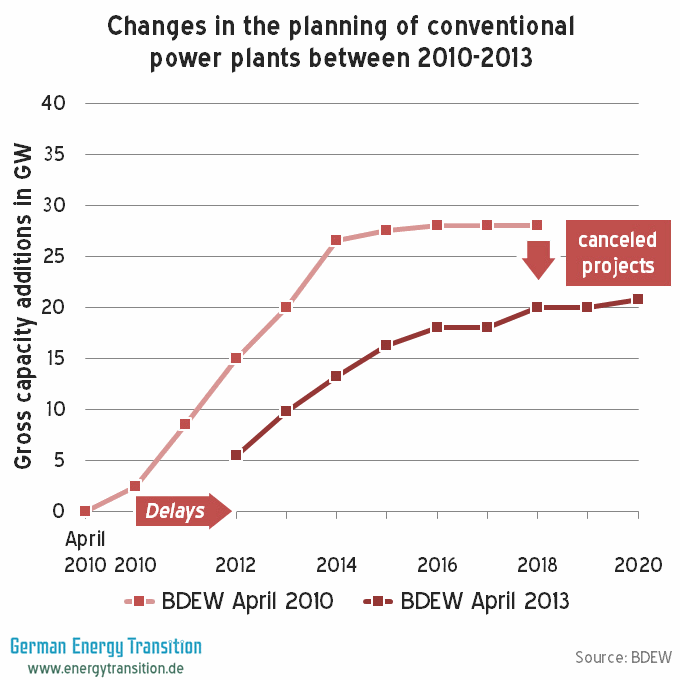

The result of the extremely low wholesale power prices resulting from surplus capacity is that new investments do not pay for themselves, so firms are delaying and canceling new builds to the extent possible. The chart below from the German Coal Conundrum illustrates this outcome well.

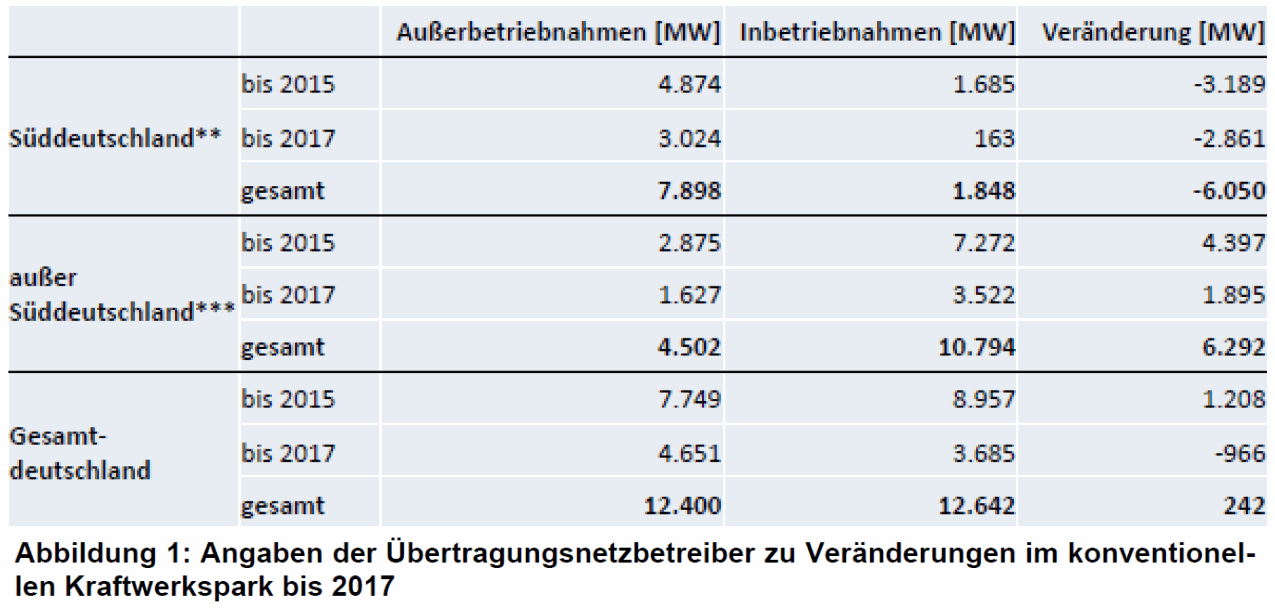

Nonetheless, experts continue to warn of a shortfall in generation capacity, this time related specifically to southern Germany – and this time, they may be right. The table below is taken from the German Network Agency’s analysis (PDF in German) of the need for backup capacity in the winter of 2015/16 published last September. It shows that roughly 6 GW of capacity will be switched off in the south, while approximately 6.3 GW will be added in the rest of the country. There is no overall change in dispatchable capacity, but there is a major shift in regional availability.

Nonetheless, experts continue to warn of a shortfall in generation capacity, this time related specifically to southern Germany – and this time, they may be right. The table below is taken from the German Network Agency’s analysis (PDF in German) of the need for backup capacity in the winter of 2015/16 published last September. It shows that roughly 6 GW of capacity will be switched off in the south, while approximately 6.3 GW will be added in the rest of the country. There is no overall change in dispatchable capacity, but there is a major shift in regional availability.

This shift is the result of the nuclear phaseout of 2011, which specifies which plants have to go off-line when. In contrast, the original nuclear phaseout of 2002 (abandoned at the end of 2010 just a few months before Fukushima) gave power plant owners some leeway in deciding which plant went off when.

This shift is the result of the nuclear phaseout of 2011, which specifies which plants have to go off-line when. In contrast, the original nuclear phaseout of 2002 (abandoned at the end of 2010 just a few months before Fukushima) gave power plant owners some leeway in deciding which plant went off when.

One way of solving this problem would be to implement that old idea of allowing nuclear plant operators some flexibility in scheduling the phaseout themselves. But this idea is not even being discussed.

Perhaps it wouldn’t work anyway. The next nuclear plant to be decommissioned does not have to shut down until the end of 2015, but the owner (Eon) recently announced plans to switch it off next spring ahead of schedule. It was further proof of the surplus generation capacity on the market, but the plant is located in Bavaria – in southern Germany. The market is now moving – predictably – in an undesired direction. With tweaking the nuclear phaseout not being discussed, policymakers will have to think of something else.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.