In a historic vote, Boulder, Colorado, remunicipalized its energy provider. Charleen Fei and Ian Rinehart explain whether this is part of a broader trend and what differentiates Boulder from other American cities fighting for control over municipal utilities.

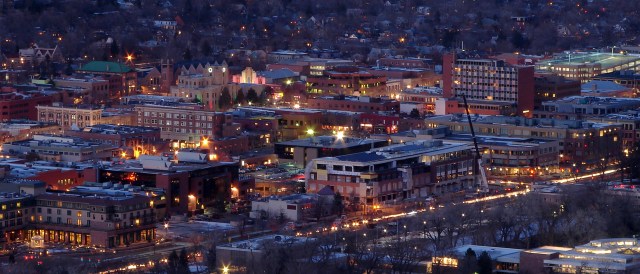

Boulder – energy by the people, for the people. (Photo by Jesse Varner, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This article is part of a series. In this first part, we highlight efforts to buy back the grid in Boulder, Colorado. In Part Two we describe the remunicipalization in Hamburg. In Part Three, we compare both cases.

In November 2013, voters from the city of Boulder approved Question 2E. This ballot measure set, among other details concerning utility choices and customer service standards, a target price of $214 million for the purchase of grid assets by the city back from Xcel, a privately owned major utility which currently services more than 3.3 million electric customers across multiple regions in the United States.

Question 2E has been lauded as a“resounding victory” in a “David vs. Goliath battle” by municipalization proponents. However, the battle is not yet over. Uncertainties remain about the administrative and acquisition details of the grid buyback, and the Colorado Public Utilities Commission has stepped in to assert its jurisdiction over Xcel assets. The resulting appeal of this decision by the city of Boulder in January 2014 is still pending.

One thing is certain: this measure has created the flexibility for Boulder city government officials and residents to start engaging – at least preliminarily – in the first steps of constructing of a local electric utility.

But why is the Boulder municipalization initiative so important?

To many observers, the events which took place in Boulder indicated not only a singular political victory for a local initiative, but the first victory of many ‘citizen initiatives’ to follow. If Boulder would break away from its private utility, the argument goes, this could spark a larger trend across the United States: from a localized community campaign to nationwide municipalization movement.

The city, for its part, hopes to be a leading example for other communities. It’s currently creating a ‘roadmap’ that could be used as an informative resource for other cities looking to municipalize their energy grids, particularly those focused on an increased pace of implementation for distributed generation or cleaner energy portfolios.

This is one possible outcome. However, the impact of the Boulder municipalization initiative must also be considered in the larger context– that of the very unique regulatory and political energy landscape in Boulder, and in the United States.

Boulder is not the first, nor will it likely be the last, community in the United States to municipalize its grid. There are currently more than 2000 communities served by public utilities, either through municipalization or Community Choice Aggregation (CCA) in the United States.

However, although some of these municipalization or CCA efforts were driven by the desire to control the mix or sources of power production, Boulder is the first city in the United States to municipalize specifically to reduce carbon emissions and increase the percentage of clean energy in its energy portfolio to meet concrete climate goals.

An assessment of Boulder’s voting demographic provides telling insight into the outcome of the November 2013 vote. Boulder is home to the National Institute of Standards and Technology as well as the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) primary national laboratory for renewable energy and energy efficiency research and development, stands a mere 30 km away. After adjusting for city size, a recent report found Boulder to be the number one city in the United States for high tech startups.

Boulder’s citizens are largely politically liberal and socially progressive. In contrast to much of the United States, Boulder’s population is uniquely educated about energy issues, invested in renewable energy technology, and willing to put in place the necessary political and regulatory measures to cut carbon emissions. Boulder remains the first and only city in the United States to have implemented a tax on carbon emissions from electricity.

To depict Xcel as the typical conservative American utility would be an unfair assessment. As an overall provider, Xcel has consistently been ranked in the top 15 utilities in the United States for its renewables portfolio and conservation programs, as well as being the number one wind energy provider in the United States for the last nine years.

Yet, in spite of this track record, Xcel has had a less than ideal relationship with the city of Boulder. The first problem emerged in the arena of managing public relations between Xcel and the Boulder citizens. Prior to the municipalization movement, Boulder was the pilot city for Xcel’s “Smart Grid City” initiative, which promised to create a “fully integrated smart grid community with what is possibly the densest concentration of these emerging technologies to date”.

However, what the citizens of Boulder were led to expect was far from what Xcel was ultimately able to offer. The project struggled to keep costs under control from the outset, installed only 101 out of 1845 promised smart devices, and lost support of partner companies. Whether it was poor expectation management on the part of Xcel or a deeper flaw in its project planning, the fact remained that the “Smart Grid City” failure left Xcel with a less than favorable public image even before grassroots organizations began campaigning for municipalization.

The second critical point of contention lies at the heart of Xcel’s business model, and the current business model of most private utilities: a lack of flexibility with regards to electricity offerings.

Electricity consumption accounted for 59.6 percent of the city of Boulder’s energy consumption in 2010, according to City’s2010/2011 Climate Action Plan Progress Report. In order for Boulder to reach its 2050 climate goals, it would have to increase the amount of electricity produced from renewable sources.

However, Boulder’s electricity as provided by Xcel came from Xcel’s larger Colorado power supply mix. Almost 80 percent of this mix is from fossil fuels – 56 percent coal and 22 percent natural gas – and about 22 percent from renewable energy sources, comprised mostly of wind power.

Despite its desire to do so, Boulder could not separate its energy consumption from the larger Colorado power supply mix. This meant Xcel was unable to provide Boulder with a customized energy portfolio centered on renewable sources.

This inflexibility is a trait shared by many private utilities. For most communities, this is not an issue. For a city like Boulder—uniquely progressive in terms of renewable energy in comparison to its peers in Xcel’s Colorado service territory—this frustrating inability to control the sources of its energy supply directly affected its ability to meet city climate goals.

This, combined with the earlier “Smart Grid City” flop, created an impression of a service provider that was neither willing nor able to meet its consumers’ needs. For over 65% of Boulder citizens, the choice between the status quo and a municipal utility was clear.

So, is the Boulder municipalization movement important? Yes, but perhaps not for the reasons with which it has been credited.

Boulder’s informed and energy-progressive voting demographic is not yet the norm in the United States as it is in Germany since the onset of the Energiewende. The ideal situation of Boulder being the first in a new trend of mainstream citizen energy initiatives is likely to remain just that—an ideal.

The most compelling argument for a municipalized energy grid in Boulder remains in the potential and free space for experimental energy policies on a community level. Xcel must make business decisions in the interest of its whole service territory, of which Boulder comprises only a small percentage.

Municipal utilities, on the other hand, may be able to create innovative energy service offerings, utilizing demand side management to trim peak loads and increase efficiency. The importance of the Boulder municipalization initiative lies in this promise.

“Taking Back the Grid: Municipalization Efforts in Hamburg, Germany and Boulder, Colorado” was written by Charleen Fei, graduate of Northwestern University currently living in Germany, and Ian Rinehart, Fulbright Research Scholar at the University of Hamburg. The full report is available as download at us.boell.org.