Foreigners sometimes quote statements made by industry experts and politicians over the past decade to show that the country did indeed conscientiously build coal to replace nuclear. That’s true, but as Craig Morris explains the outcome was that, contrary to these expert expectations, renewables replaced nuclear, so we are now left with excess coal capacity. Part 2 of a 3-part series.

(Photo by begangenes, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

German politicians do not tell the energy sector what to build. In fact, in the same article from 2009 mentioned in Part 1, Gabriel says the decision of what power plant to build is “up to the company, not politicians.” Nonetheless, plans to build the power plant in question in that article were discontinued in September 2009, when the company decided the economics were too uncertain.

In its newsletter published just weeks before Fukushima, energy sector publisher Montel speaks of overcapacity on the German market.

Obviously, the economic crisis had happened in the meantime, but coal power plants have service lives of 40-60 years. Over the past few years, energy firms have come to realize that renewables alone can replace nuclear, so they are struggling to stop projects wherever possible. Since March 2011, when Chancellor Merkel decreed that eight of the country’s 17 nuclear plants had to be shut down immediately, not a single coal plant has been added to plans – but six projects underway had been scrapped as of November 2012. This month, German utilities organization BDEW explained that 43 percent of current new capacity plans might be canceled.

The problem has become clear: conventional plants will increasingly run at a lower “capacity factor,” meaning fewer hours per year. Because natural gas is more expensive than coal in Europe, gas turbines have been hit first. According to figures published by German utilities organization BDEW, the capacity factor of gas turbines fell from 39 percent in 2010 to 30 percent in 2012. Coal is next to go.

While Gabriel may not have been right about current need, he may still turn out to have been prescient about what will be needed by 2022, when Germany switches off its last nuclear plant. But before we get to that, let’s look at Germany within its European context for additional insights.

Emissions trading and the Industrial Emission Directive

To whatever extent the boom in plans for new coal plants starting in 2005 may have been a reaction among energy providers to a perceived gap left behind by nuclear, we still have to account for the surge in coal; after all, the firms could have invested in natural gas and renewables.

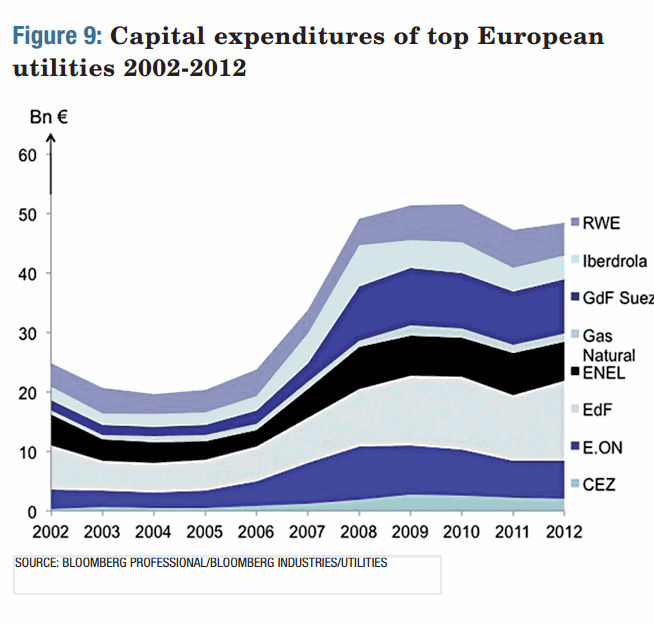

The surge in capital expenditures (capex) was not solely a German phenomenon. Indeed, as a recent study published in February 2014 by Greenpeace points out (PDF), investments roughly doubled among the major European utilities from 2005 to 2008 – but only Germany had an official nuclear phaseout.

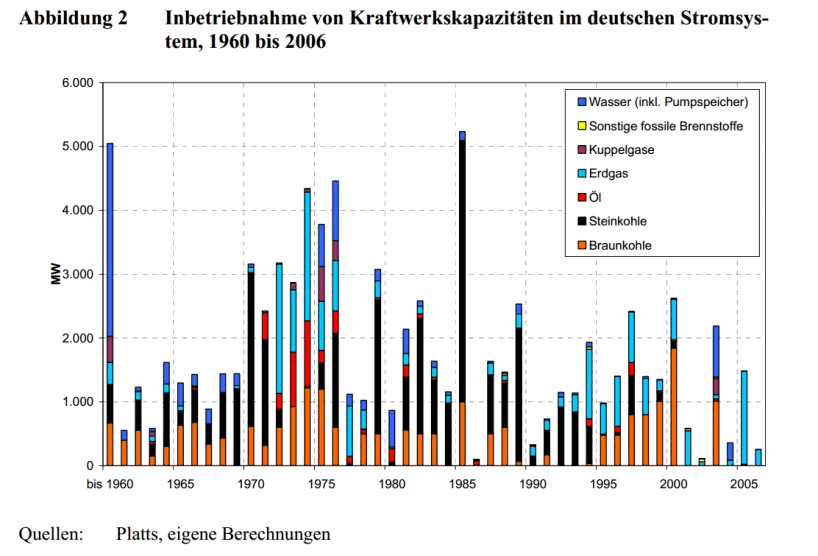

Greenpeace writes, “It is not entirely clear why large utilities increased their capex so much,” but we have identified three factors. First, not a lot of plant capacity had been built in the period from around 2000-2005 (see Platts chart). It was the era that marked the end of monopoly power sectors and the beginning of regulated, but liberalized power markets. Utilities understandably took a wait-and-see approach.

Second, in 2005 the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) went into operation. In the first two phases up to the end of 2012, more than 90 percent of emissions credits were handed out to power producers for free. The result was windfall profits, which gave these firms more liquidity to invest. The combined effect of the economic downturn after the financial crisis (lower demand for energy) and the rise of renewables reduced carbon emissions from the power sector below what was expected. As a result, the price of carbon is not the 30 euros per ton anticipated, nor the 50 euros that some environmentalists hoped for, but closer to five euros at the beginning of 2014. In short, ETS failed to provide an incentive for power companies to switch from coal to natural gas.

Third, the EU adopted stricter requirements for coal plants at the beginning of 2008. Plants that failed to meet the requirement have to shut down by 2016. When we remember that it takes around six years for a coal plant to be built, plans for a new coal plant to replace one decommissioned in 2016 would have to begin by 2010 at the latest.

In other words, Europe had an aging fleet of power plants, and coal capacity in particular needed revamping. Emissions trading failed to encourage a shift to natural gas, and new nuclear is controversial everywhere, so the firms opted to replace old coal with new coal. Obviously, renewables would have been an option, but the firms simply did not believe in it.

Although big utilities can take advantage of the same feed-in tariffs offered to everyone, RWE, one of Germany’s two biggest power providers, has only four percent renewable power in its generation, whereas renewables covered 25 percent of German power demand in 2013.

Renewables do the job

Before we get back to why Industry Minister Gabriel might yet be right about a simultaneous nuclear and coal phaseout being difficult, let’s take a closer look at how renewables have performed since 2003, when the first nuclear plant was phased out.

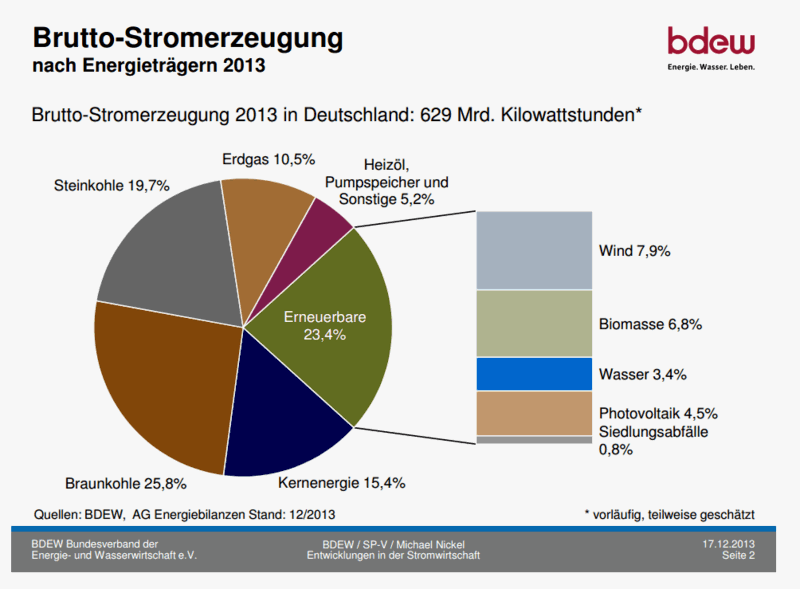

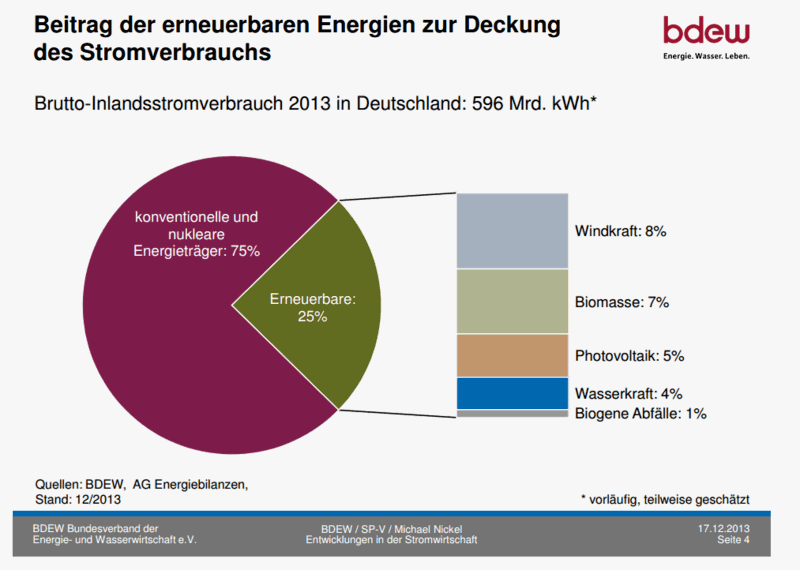

From 2003-2013, the total share of coal power drops from around 50 percent in 2003 to around 46 percent in 2013, with nuclear dropping from around 27 percent to around 15 percent, while natural gas stays stable at around 11 percent – but renewables rise from around seven percent to 24 percent. Clearly, in terms of terawatt-hours, renewable electricity has not only replaced nuclear entirely, but also cut into demand for coal power.

From 2003-2013, the total share of coal power drops from around 50 percent in 2003 to around 46 percent in 2013, with nuclear dropping from around 27 percent to around 15 percent, while natural gas stays stable at around 11 percent – but renewables rise from around seven percent to 24 percent. Clearly, in terms of terawatt-hours, renewable electricity has not only replaced nuclear entirely, but also cut into demand for coal power.

The uptick in coal power production over the past two years has to be seen against the backdrop of Germany’s rising net power exports, with the two biggest buyers being the Netherlands and France. When the BDEW tallies statistics for “gross power production,” it includes power for export. For 2013, the utility organization reports that renewables made up 23.4 percent of gross production.

But when the organization subtracts the roughly 5 percent of power generation exported, the share of renewables increases for 2013 to 25 percent – because renewables have priority on the German grid and would otherwise have offset the conventional power exported. Wind and solar power in particular are generated regardless of demand and are therefore unaffected by the export/import situation.

But when the organization subtracts the roughly 5 percent of power generation exported, the share of renewables increases for 2013 to 25 percent – because renewables have priority on the German grid and would otherwise have offset the conventional power exported. Wind and solar power in particular are generated regardless of demand and are therefore unaffected by the export/import situation.

In the final installment of this series, we learn how Minister Gabriel might be right after all – and how coal plants could be in a safe position over the next decade nonetheless.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.