In social media, one new meme seems to be that Germany is too dependent upon energy imports from Russia to take a strong stand on Ukrainian independence. Craig Morris says those commenters confuse energy with natural gas, and they overlook Russian dependence on Germany and the EU.

The GUM department store in central Moscow overlooking Red Square, where military parades are often held. Will the current crisis in Ukraine have mainly commercial impacts, or will it become more military? (Source: Harry-Hautumm | pixelio.de)

Germany imports a lot of natural gas and oil from Russia. In fact, Russia makes up around a third of Germany’s total natural gas supply. But in 2012, natural gas only made up around 21 percent (statistics in German) of German energy supply from 2000-2012 (in terms of primary energy). Imports of Russian natural gas thus constitute seven percent of German energy supply.

Oil makes up around a third of German energy supply. Slightly more than a third of this oil is imported from Russia, so add on another 12-13 percent. Germany also gets roughly a quarter of its hard coal from Russia, with hard coal coming in at a little over 12 percent of primary energy supply on average in the past five years – so add on another three percent, and Germany gets roughly 22-23 percent of its primary energy from Russia. That makes Russia Germany’s single largest energy supplier. The figure floated on social media is closer to 40 percent dependency.

Does that make Germany dependent on Russia, or Russia dependent on Germany? In recent years, the dispute between Russia and Ukraine has drawn a lot of attention, but one fact has been overlooked – the Ukrainians do not have to pay market prices. Russia offers Ukraine a “friendship discount,” which was recently a third of the price countries like Germany are willing to pay. In the current conflict, Russia is once again using this discount to its advantage. But if the Russians lose the Germans as customers, they lose a client paying top dollar.

It’s quite possible that the current conflict will lead to gas supplies to the EU via Ukraine being cut off completely for a time, though Germany has had its own direct gas pipeline under the North sea for the past few years. Depending on what facilities are in place for international shipping, Germany and the EU will simply switch to other sources on international markets – something more easily done for oil than natural gas.

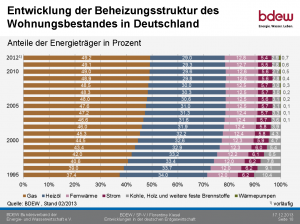

The share of natural gas in space heating has increased over the years in Germany and is now nearly 50 percent, with heating oil still coming in close to 30 percent. In contrast, electricity only covered 5.4 percent of heat demand in 2012. The current crisis in Ukraine is therefore unlikely to affect Germany’s nuclear phaseout because nuclear only provides electricity. Source: BDEW

Some nuclear proponents seem to think that Germany’s nuclear phaseout has made it more dependent on Russian gas, but nuclear is only used to generate electricity, and as the official statistics for gross power production in Germany show the share of natural gas was down by 1.6 percentage points in 2013 to a mere 10.5 percent, considerably lower than the 14.1 percent in 2010 (before Merkel’s nuclear phaseout in 2011).

Should energy supplies slow down, Russia might suffer more than the EU, which can try to source supplies elsewhere. But lost sales revenue through Ukraine really is lost for the time being, and economic warfare against Russia has already begun.

For the Energiewende, the main outcome is likely to be a focus on domestic supplies. Brown coal will be the biggest benefactor. Already, Germans who support a coal phaseout have a hard time explaining why Germany should forgo such an inexpensive domestic source of energy in return for more expensive natural gas imports from a troublesome neighbor. A prolonged, intensified Ukrainian crisis will make Germans even fonder of their only major domestic source of dispatchable energy.

One bizarre thing about this conflict is how differently it is perceived than it would have been a few decades ago. Although the risk of World War III – including the use of nuclear weapons – still exists and we still have enough nuclear arms to destroy the planet, the Cold War is over, so the perception of this risk is calmer. Europeans are now mostly concerned about economic impacts, not the ever so slight chance that civilization might not survive this conflict.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.