The Anglo world repeatedly reads news about Germany’s changes to energy policy as a sign that Germany is abandoning renewables. Craig Morris says the misunderstanding is cultural; the success of Germany’s switch to efficiency and renewables, macroeconomic.

The Energiewende continues to enjoy broad social support in Germany. (Photo by 350.org, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As an American who has been living in Germany for almost all of his adult life, I understand the difficulty of writing about other countries. Some reports are obviously ideological and intentionally misleading, but not all.

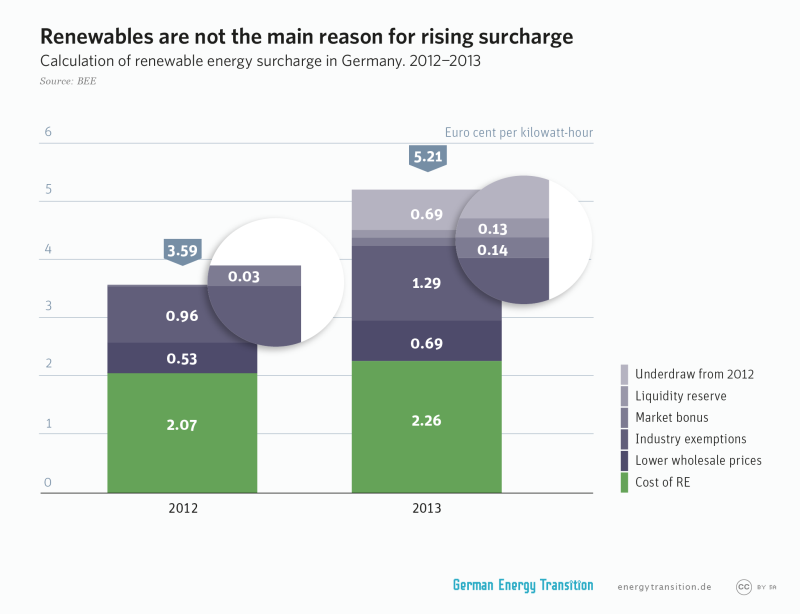

Take Robert Wilson’s claim a recent post at Carbon Counter that the “future growth of renewables is now in doubt” in Germany. Wilson links to the proposed ceiling on the renewables surcharge. Too bad he has not heard the news that the planned ceiling was completely thrown out last month, nor would I expect a Glaswegian to know that the actual cost of renewable power only makes up around 40 percent of that surcharge. (But as someone who tries to cover energy disputes between Scotland and England from Germany, I sympathize with his plight.)

A bigger problem is that Wilson does not even address the goal of Germany’s Energiewende, which is not to provide a low kilowatt-hour price while lowering carbon emissions and switching to solar (a combination he rightly calls an “absurdity”).

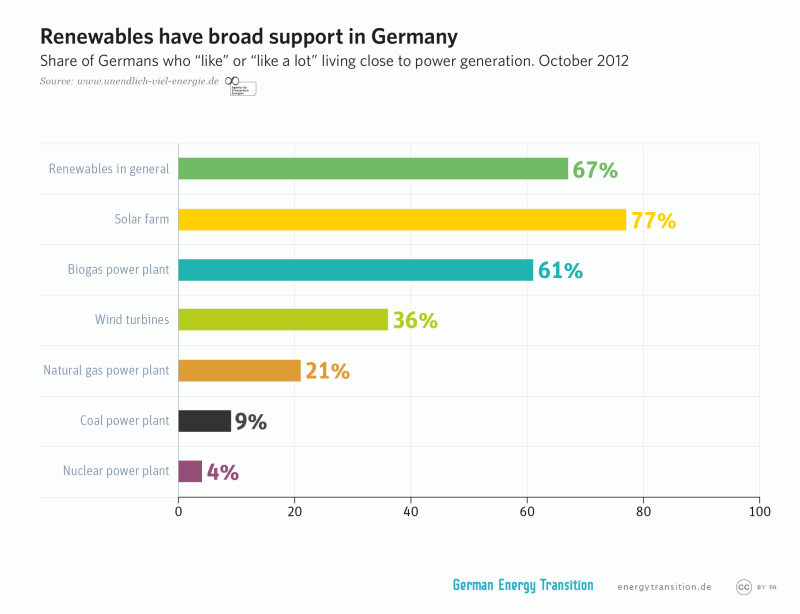

Rather, since the 1970s, the goal has been to allow citizens and communities to make their own renewable energy. A focus on low prices is microeconomic thinking. Germans take the macroeconomic view and want to know whether that price is paid to large corporations, foreign entities, or back to their community. They are willing to pay higher prices back to the latter.

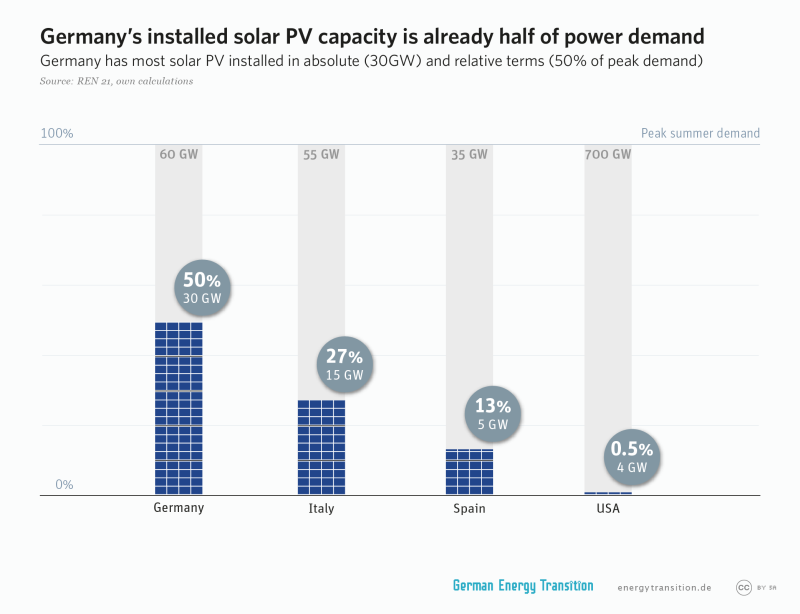

Germany is not switching to solar, either – it switching to renewables, and only with far lower consumption. Wilson himself has already written about the limits of biomass, and Germans would agree. But he does not describe the limits of solar well; the capacity factor is irrelevant. As we describe in our section on solar, peak summer demand is the real limit. Last year, Germany got less than five percent of its electricity from PV although installed solar capacity was roughly half of peak summer power demand. By the time Germany gets 10 percent solar, the country will not be able to absorb all of the PV power it produces – so Germany will have trouble going beyond 10 percent PV in its power supply.

[Update: Via Twitter, Wilson has pointed out that he indeed reached that very conclusion last year in a separate blog post where he even cites our chart above. Although he calls the chart “misleading,” he nonetheless draws the very conclusion from it that we intended.]Finally, the proposed switch to natural gas is nice in theory but not in practice. Natural gas supply in Germany is currently at a record low, partly because German traders are selling at a premium to the UK, where gas for domestic heat is in even shorter supply; thanks to the British focus on low prices, they do not have sufficient natural gas storage. The British press reports that people are freezing to death, and a recent report found that 5 million households in the UK were behind on their energy bills. It thus seems that energy poverty is a greater concern in the UK than in Germany despite the focus on low prices.

Ironically, it seems that the German focus on a diverse mixture of energy sources (and quality, not low prices) is helping prevent energy shortages in France and the UK – not the outcome Energiewende critics expect, but then nor is Germany’s current economic strength and unemployment rate, with the latter being at its lowest rate since reunification more than 20 years ago.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

Nice reporting. As an ex-pat, Nam vet in Munich, I was not aware this blog existed in English. Good stuff. Need contributions. I was just at an ÖDP meeting with Axel Berg, ex assistant minister of environmental protection during the Red-Green, and Black-Red coalitions, now CEO of the German division of Intersolar. There are problems in the transition, but it is irreversable. I think more emphasis should be placed on the “merit order effect” of rnewables and energy efficiency measures.

I work in the field myself, so I will stay in touch.