Why is Germany still planning on building another pipeline for Russian gas? Investing money in new gas infrastructure makes no economic sense, as falling costs for renewables could cut gas consumption in half by 2030. Paul Hockenos takes a look.

Nordstream 2 will be a costly millstone around Germany’s neck by the 2020s (Photo by Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0)

It’s nothing short of dumbfounding that the furious debate over Nord Stream 2 – the controversial natural gas pipeline that will run beneath the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany – completely ignores Europe’s commitment to transition to renewable energy and lower greenhouse emissions.

The debate over the gas conduit has raged in Europe and across the Atlantic as if the 2015 Paris climate accord, the purpose of which is to keep global temperatures beneath a two-degree Celsius rise, never happened – and as if natural gas has nothing to do with global warming.

It’s such a farce – the environmental arguments against the Gazprom cash cow so overwhelming – it makes one wonder whether Germany and its peers take their renewed pledges to protect the climate seriously at all.

The very best reason to nip Nord Stream 2 in the bud – the construction of which has begun, though key construction permits are outstanding – is that it’s already obsolete, and will be a very costly millstone around Germany’s neck by the 2020s when it’s supposed to be operational. Europe and Germany, the latter Nord Stream 2’s primary client, simply don’t need another gas source: they have access to more than enough gas from Russia and other suppliers. And in the near future Germany will need less, not more, as it weans itself off fossil fuels (which natural gas is, despite the industry’s deceitful campaigns to convince us to the contrary.)

Natural Gas Supply: No Need for Another Baltic Sea Pipeline. Anne Neumann, Leonard Göke, Franziska Holz, Claudia Kemfert, Christian von Hirschhausen In: DIW Weekly Report 8 (2018), 27, page 241-248

There’s already one Nord Stream pipeline, which boasts an annual capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (bcm), alone more than half of Germany’s annual consumption. But it and other sources thoroughly satisfy European demand, as recent reports (in English) from the German Institute for Economic Research and environmental think tank E3G conclude.

Indeed, back in 2006 and 2009 there were gas crises in Europe (let’s not forget, caused by Russia) but conditions now are very much changed. The EU has addressed the over-reliance on Russian natural gas by diversifying sources and expanding gas infrastructure.

“The European gas market at the end of 2019 will not be anything like the market in 2009,” writes Siobhan Hall, EU energy editor at Platts, a media outlet for the energy sector. “It will be vastly more resilient to gas supply shocks from any direction, thanks to the EU’s efforts to tackle the vulnerabilities exposed by the 2009 crisis.” Other experts, including the EU’s Court of Auditors, underscore that the figures regularly used in the debate for projected natural gas consumption in Europe are dramatically inflated and have been for years.

Moreover, new scenarios show that even if Russia cut off gas exports in the thick of an arctic winter, Europe could switch to other sources – not least highly diversified liquified natural gas (LNG) deliveries — and survive the icy climes while cozy in their living rooms. In fact, the studies show that Europe, and Germany on its own too, now has abundant extra capacity on tap: mostly in terms of LNG, which could be tripled upon demand, if necessary, as well as plentiful gas in storage facilities.

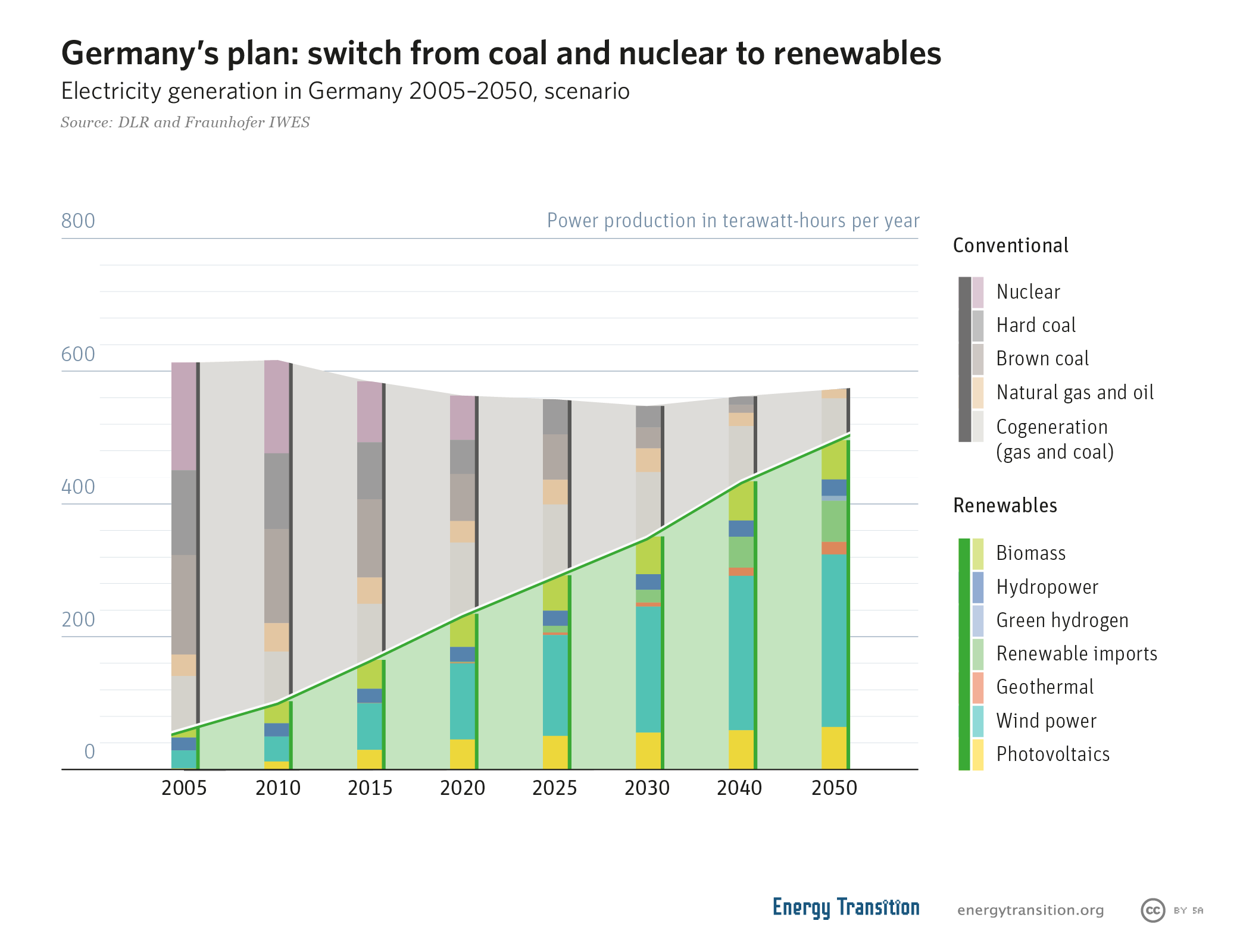

And then there’s the scandalously unspoken climate protection goals: Europe’s consumption of gas is scheduled to diminish, steadily, between 2020 and 2050 when Europe will run almost exclusively on renewables. Simulated models show that globally between 2020 and 2030, natural gas consumption will drop by half, and then by 2050 be nearly zero as renewable energies, including organic bio-gases, take over.

As for Europe, which has pledged to cut in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels 40%, some models also show that in light of the falling price of renewables, a 50% reduction of gas consumption is possible by 2030.

In Germany, natural gas is responsible for 20% of carbon emissions – it’s not climate friendly. And, furthermore, there are renewable gas alternatives that are being expanded: biogas, power-to-gas, other synthetic fuels. The latter are in their infancy and will, in part, replace the natural gas we need as energy efficiency and electrification reduce consumption.

Of course, the gas industry underscores that gas is (or was) foreseen as a bridge technology. As coal and nuclear dwindle in energy supplies, wind and power must be balanced out. But neither does Europe need yet another source of natural gas to do this nor is there a consensus anymore on gas’s importance to the global Energiewende.

The DIW report charges that “in the long term, the importance of fossil natural gas will decrease in Germany’s energy supply.” It concludes that, “In view of low electricity prices for the foreseeable future, high overcapacities in the conventional power plant sector, and rapid progress in the development of renewable energies and storage technologies, fossil natural gas will no longer have any significance in the electricity industry as a bridge technology.”

This battery of arguments should lead the way in killing off Nord Stream 2 – it’s not too late. There are other good reasons too: the pipeline’s high cost to European consumers, the concerns of the Eastern Europeans, the geopolitics of reliance on Russia, Russia’s pariah status since annexing Crimea in 2014, and the vast environmental damage caused by its construction.

But sometimes the most compelling reasons are those closest to hand: we simply don’t need the gas from Nord Stream 2. And, scandalously, it flies in the face of the Paris accord after a sizzling summer that has only heightened its urgency.

[…] Source: Energy Transition […]