The New York Times says they are “positive for energy users.” But Germany’s newspapers Handelsblatt and Der Spiegel say that Germans are paying neighboring countries to take excess power off their hands. Who is right? Craig Morris investigates.

German power exports are more valuable than its imports, but that situation is likely to change for good soon (Public Domain)

UPDATE: The table used has been updated to correct a math error noted in the comments, as has the accompanying text.

There aren’t too many goods or services that you get paid to consume. So how do power prices go negative?

Basically, electricity is a rare commodity in two respects. First, it has no shelf life and is therefore consumed immediately. Second, power plants can’t always be easily stopped and started again like some production lines. It may be cheaper for a power plant to pay you to consume more power than ramp up and down.

But “you” probably don’t get paid to consume power. Negative prices only occur on the wholesale exchange. Retail customers can’t buy there, so they don’t benefit. You only benefit if you can purchase wholesale power – and even then, only if you can use it at those times.

So when the New York Times writes that negative power prices are “positive for energy users,” that’s not really accurate. Indeed, Handelsblatt and Der Spiegel are perhaps more correct because ideally you want to keep hours with negative prices to a minimum. Paying people to take electricity raises costs overall.

More generally, however, all of these analyses fall short. Negative prices are useful as a market signal for demand shifting and storage, and they will become more common as shares of wind and solar power grow. More importantly, what matters is not a few hours, but the annual balance. And that looks quite different.

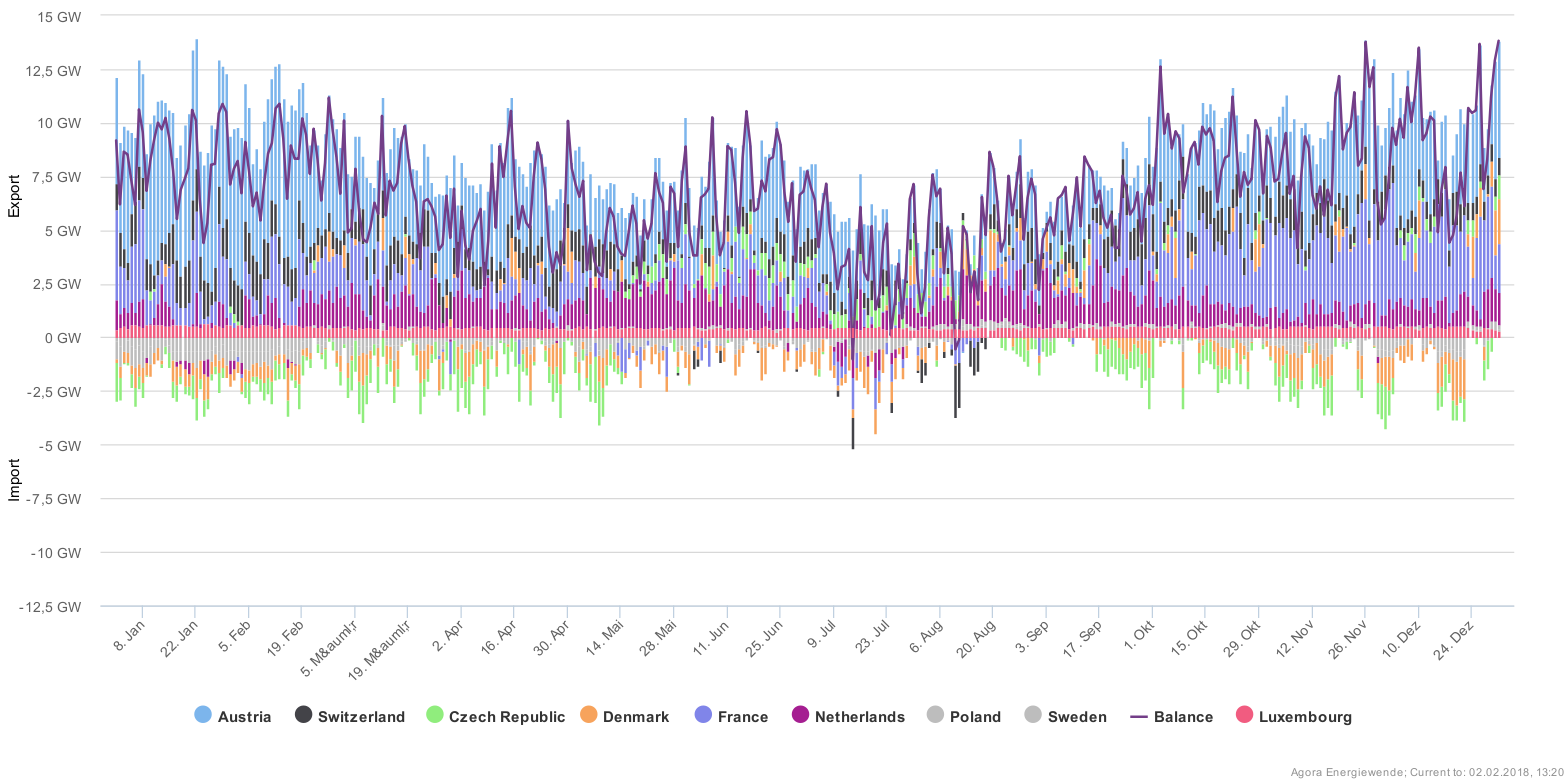

Because Germany still have so much excess generation capacity (too many conventional power plants), it is still able to export power when neighboring countries need it. Power demand in and around Germany is generally higher in the winter and lower in the summer. The chart below showing commercial power trading reveals more exports during the winter – at times of higher demand – than in the summer.

The table below, with power trading statistics for 2016 (the last year available) from the German Statistics Office DeStatis, shows the price impact from physical flows. (Germany does not trade electricity with Belgium, though they share a border, and only exports to Luxembourg.) Germany not only exports some three times more electricity than it consumes (78.3 TWh out, 27.4 TWh in), and the average price of a kilowatt-hour exported is slightly lower at 3.52 cents than of a kilowatt-hour imported at 3.70 euros. These prices apply to physical flows; for instance, France uses the German grid to sell electricity to Switzerland and even Italy – the Germans don’t consume that power directly.

I have marked the higher price averages in red. The only country Germany has a negative trade volume with (more kilowatt-hours imported than exported) is Sweden, and the average kWh price is slightly lower for exports than imports in this case. The average value is greatly lower for trading with Denmark, Austria, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland. It is positive for France, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic.

The French outcome is noteworthy. At the end of 2016, a third of its reactors were off-line, and the country was having trouble meeting its own domestic power demand. Just a few years ago, French power sold to Germany was much less valuable per unit than what Germany sold to France, largely because the French dump nuclear power at low prices on neighboring countries when demand is low to avoid having to ramp down its fleet further. Now, the price difference between the two countries has leveled off, with French prices still slightly lower on average, but the volume of electricity Germany sells to France more than tripled, while imports from France to Germany were cut in half since 2014. The numbers for 2017 will be all the more interesting; how did the French shortfall impact trading with Germany?

Overall, German power exports are only slightly less valuable than its imports, but that situation is likely to worsen next decade. The nuclear phaseout will remove nearly 10% of dispatchable generation capacity by the end of 2022, and the push for a coal phaseout will take off even more. Critics of the Energiewende view these hours of negative prices as evidence that Germany is dumping excess renewables on the neighboring countries, on whom it allegedly relies for grid stability. Clearly, the opposite is currently the case. But there may be more truth to that reading five years hence.

After EasyEnergy a second trader (EnergyZero) is now offering household electricity at EEX prices, so negative prices are also available to the final consumers if they do occur – in the Netherlands:

https://easy.com/shareholder-news/4664-easyenergy-sir-stelios-backs-new-netherlands-smart-meter-project-to-reduce-home-power-bills.html

https://www.energyzero.nl/

A report on the issue in the Dutch AD

https://www.ad.nl/economie/hoge-energierekening-ga-voor-stroom-per-uur~a7d78cca/

PS

Free energy is offered – if available at the exchange:

“Wordt energie in de toekomst gratis?

Er gebeurt van alles in de energiemarkt. We gaan steeds meer elektrische apparaten gebruiken. En er worden steeds meer duurzame energiebronnen gebruikt zoals windmolens en zonnepanelen. Deze veranderingen scheppen nieuwe mogelijkheden om energie anders te gaan afrekenen. Van hele dure uren tot misschien wel gratis energie.”

see

https://www.energyzero.nl/vernieuwend/flexibele-energietarieven/

I dot get your numbers to match. average price should be price/amount. but for Denmark (first in list) price for exports are 128607€ (asumming thousands of € or else Denmark got a bad price) and export is 5266084 Mwh. that gives us 128607000/5266084 for €/Mwh and it is 24.42 €/mwh. but you ave a pricelist of 4.1(something.) if we do the same calculation on imports we get 115278000/3399223=33.91€/mwh This is the exact opposite of your conclusion. the imports are very much more expensive than the exports. (almost 10€ in difference.)

And if we do the same math for France we get.

exports: 97352000/2731747=35.36€/mwh

imports 287009000/8315776=34.51€/mwh

so a small profit not a small loss.

It seems like your numbers are consistently mixed up and your conclusion should be the opposite of the one you have drawn.

Best regards

/christoffer

This entire article is based on faulty math. Every price advantage comparison that is made is the opposite of what claimed. The basic error is that the author switched numerator and divisor. For instance, the total average export price per kWh is not 2.84 cents/kWh, but 3.52 cents/kWh and import is at 3.70 cents/kWh. I’m laughing so hard here! The idea that Sweden would sell hydro cheap and import lignite/wind expensively… Starting the countdown to when the article is pulled down now.

Very strange indeed. A link to the original data would clarify a lot

[…] It may be cheaper for a power plant to pay you to consume more power than ramp up and down,” explains Craig Morris, co-author of Energy Democracy, the first history of Germany’s […]