While Germany roars ahead with renewable electricity, too little is happening with heat and transportation. Now, a study finds that Germany is likely not only to miss its carbon reduction target by the end of this decade, but also the target for the share of renewables in all energy. Craig Morris says the Germans are clearly stumbling through their Energiewende – and that’s good news for other countries going down a similar path.

If Germany wants to fulfill its climate targets, it needs to be more ambitious with heat and transport.

Did I recently say that Germany might be on target for renewable electricity, but it will not meet its 2050 target for renewable energy until 2097 at current rates of progress?

Now, a leading German energy analyst has put a finer point on my rough estimation. The short study conducted on behalf of German renewable energy association BEE is only available in German (60-page PDF). The author is Joachim Nitsch, who knows exactly how to make such scenarios; he was a chief contributor to previous Leitstudien (official governmental roadmaps).

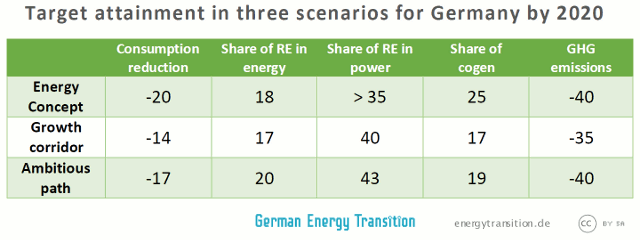

The study focuses on three main scenarios:

- the government’s own Energy Concept,

- a path within the growth corridor for onshore wind power, and

- a more ambitious trend towards a 95 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2050.

The main takeaway is that the growth corridor – 2.4 to 2.6 GW of annual new capacity net for onshore wind – will produce a much higher share of renewable electricity, but the target will not be met for total energy, cogeneration, or greenhouse gas emissions. Germany’s Energiewende is clearly still an electricity transition, not a true energy transition. Here, some tweaking still needs to be done.

Another interesting finding is that the government’s own growth corridor does not tally with its Energy Concept. The latter was more or less created in the ivory tower with few political constraints, whereas the former is the political implementation of that concept – including real-world bargaining.

Not surprisingly, Nitsch says that the German government’s “current Energiewende policy still lacks a coherent strategy to tackle all sectors by 2050.” Admirers of the Energiewende sometimes depict it as a master plan of German engineering in combination with that magical German ability to reach a consensus across party lines and throughout society. Interestingly, the Energiewende’s critics seem to agree that this combination exists, though they depict it as practically Soviet-style central planning based on a green ideology that permeates all of German society. In reality, the German Energiewende consensus has to be renegotiated continually. And while the targets for 2050 are set, German engineering and political masterminds don’t know how to get there any more than experts in other countries do. The Germans are stumbling through the Energiewende experiment, working to correct mistakes as they go along. Germany’s energy transition is an iterative process, and Nitsch’s study is intended as troubleshooting so that problems can be fixed.

In the transport sector, Nitsch calls for “a considerable increase in efficiency” in the short and midterm, including a modal shift and changes in mobility behavior – in other words, people should begin combining different modes of transport (trains, public transportation, cycling & walking, and rental cars/car-sharing) rather than just taking their own car. In the heat sector, he argues that the current restrictions for biomass (particularly the tiny target of 100 MW annually) will slow down renewable heat. In no scenario does Germany come even close to its target for the share of cogeneration.

The study is food for thought for international onlookers as well. Too many media reports conflate peak renewable power production with the share of renewable energy. Thus, we read that Germany is 50 percent solar or three quarters renewable – even though renewable energy currently only makes up 11 percent of total energy supply. And that figure is only growing slowly.

The good news for other countries is that tackling an energy transition does not require any technical expertise or social consensus that only Germany has. If the Germans can stumble towards a renewable energy future, others can as well.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.

According to German press releases the big polluters want the goverment to pay them for closing power plants.

‘RP online’ considers this deal to be nearly done, RWE wants to close Niederaussem with a total of 1.2 GW of lignite power.

http://www.rp-online.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/branche-will-abwrackpraemie-fuer-kraftwerke-aid-1.5161912

I have my doubts, competition laws (national and international) are against such deals.I’d say: just wait,they’re nearly dead anyhow.

And paying to close the plants means in lay men terms paying to get the culprit from the gallows.

That Germany would be missing its own climate targets can only be concluded with the status quo being a fixed assumption for the future.

The dinos are dying, until 2020 at least two of them will have ceased existence.

Burring their body under a heap of debts means technically a sell-out at the end to satisfy the lenders. And the existing fleet of power plants has no chance to be sold on. There is a good reason why EoN has split their company and re-baptised the trash.

The neighbors of Germany might do better, low power prices are forcing coal and atomic power plants down.

News are just in from the Netherlands (in Dutch language) – a 420 MW blood-coal power plant has to close due to low power prices:

http://www.omroepzeeland.nl/nieuws/2015-06-22/883614/fors-minder-winst-voor-elektriciteitsbedrijf-epz#comment-115084

From Switzerland German TV reports yesterday (in German language) that 3 atomic reactors are in financial trouble since last year due to low power prices:

http://www.swr.de/landesschau-aktuell/bw/suedbaden/schweizer-atomkraftwerke-bund-stellt-wirtschaftlichkeit-in-frage/-/id=1552/did=15714246/nid=1552/1kxo543/

The German Energiewende is a failure as a Climate Strategy.

When the 2013 Greenhouse Gas Emissions are released next week by the EU, per capita German emissions will have INCREASED since 2007# – the date of the EU mandate.

From 2007 to 2012, Danish per capita GHG emissions are down 22.4% and French emissions (from a MUCH lower level than Germany & Denmark) are down 11.4%. French per capita emission are now lower than Chinese. I await their 2013 #s.

Meanwhile, Germany forced *UP* all EU GHG emissions by vetoing vehicle fuel standards in the EU. Selling big Mercedes, BMWs and Audis is more important than the Climate.

Germany is Climate laggard – despite all their publicity and propaganda. Look instead to the French and Danes (and Panama & Ethiopia) on how to effectively reduce GHG emissions.

#Using 1990 as a baseline was a clever trick. That way Germany could use Soviet style industry and brown coal heating in Eastern Germany.

Dear Alan,

it seems like you are cherrypicking your data. First of all, France has experienced a much lower growth since 2007 (11% vs. 16%). On top, Germany corrected its number of citizens in 2011. Since then, we calculate with around 1 mio. inhabitants less, even though nothing as changed on the ground – so data from after necessarily 2011 indicates a higher per capita carbon intensity. Picking 2007 as a base line is a clever trick, as you call it, too, as emissions in that year were much lower than in the year before or after. Anyway, German emissions between 2006 and 2014 have sunken 10%, between 2007 and 2014 around 7%. If you take the growth of GDP in account, Germany’s decarbonisation was actually faster then France’s (even though, as you said, France starts from a lower baseline).

I agree that Germany needs to get more ambitious when it comes to the emissions from the transport sector, where it hasn’t played a constructive role on the European level.

Best,

Alexander